Q2 2025 Conference Call

Edited Transcript of the 2nd Quarter 2025 Conference Call with Dave Iben and Alissa Corcoran

Kopernik reviews the audio recording of the quarterly calls before posting the transcript of the call to the Kopernik website. Kopernik, in its sole discretion, may revise or eliminate questions and answers if the audio of the call is unclear or inaccurate.

July 24, 2025

4:15 pm ET

Mary Bracy: Good afternoon, everyone. I’m Mary Bracy, Kopernik’s Managing Editor of Investment Communications. We’re pleased to have you join us for our second quarter 2025 Investor Conference Call. It was an eventful quarter, so we’re looking forward to hearing from Dave and Alissa today. As a reminder, today’s call is being recorded. At any point during the presentation, if you have a question, please type it into the Q&A box, and we’ll be happy to answer it as a part of our Q&A session at the end of the call. Now I will turn the call over to Mr. Kassim Gaffar, who will provide a quick firm update.

Kassim Gaffar: Thank you, Mary. Welcome, everyone, to the second quarter 2025 Conference Call. I have with me Dave Iben, our Co-CIO and Lead PM for the Kopernik Global All-Cap strategy and Co-PM for the International strategy, and Alissa Corcoran, our Co-CIO, Co-PM for the Global All-Cap strategy [and Co-PM for the International strategy], and Director of Research. Before I pass the call to Dave and Alissa, I’ll provide a quick firm update.

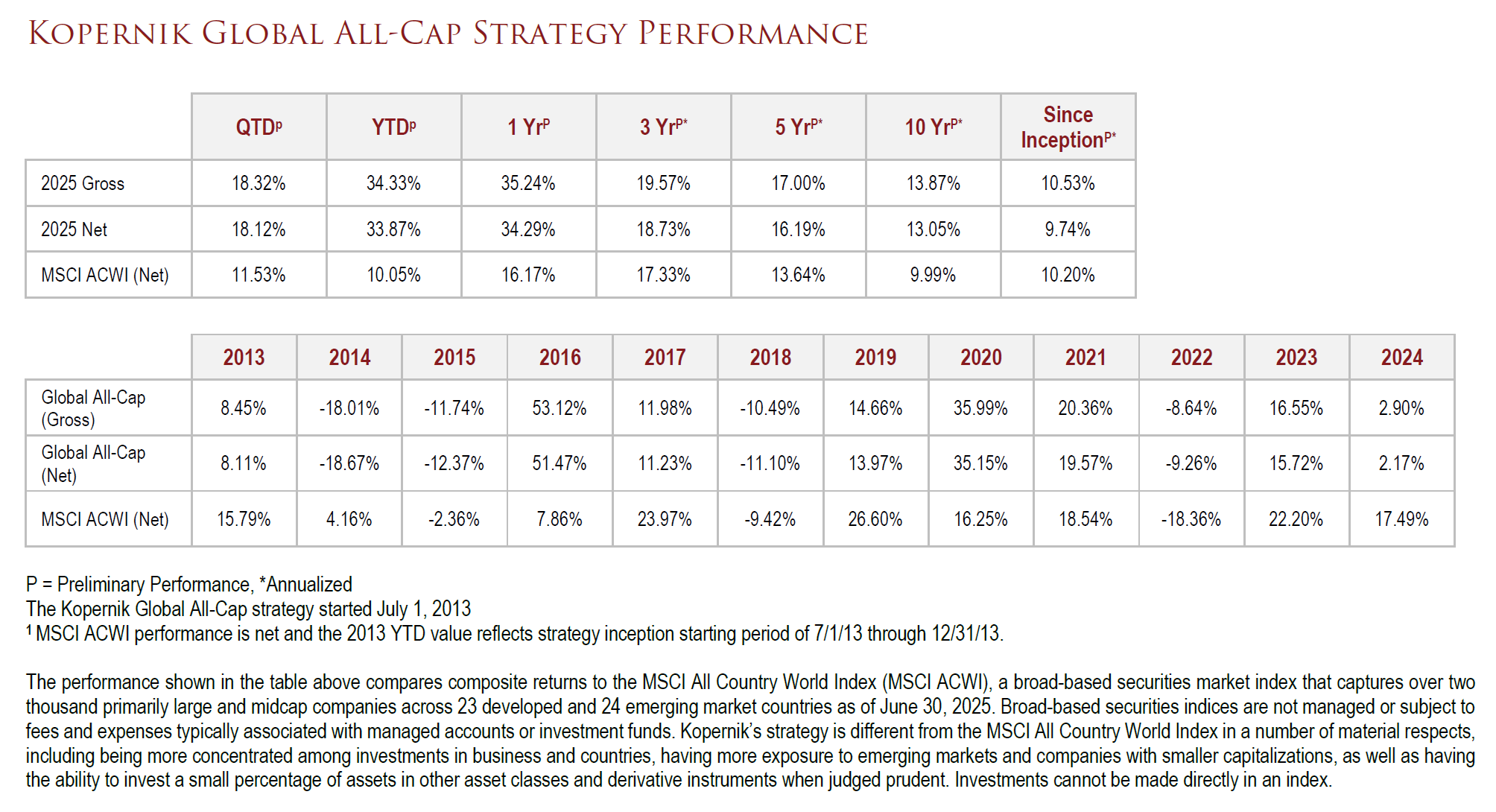

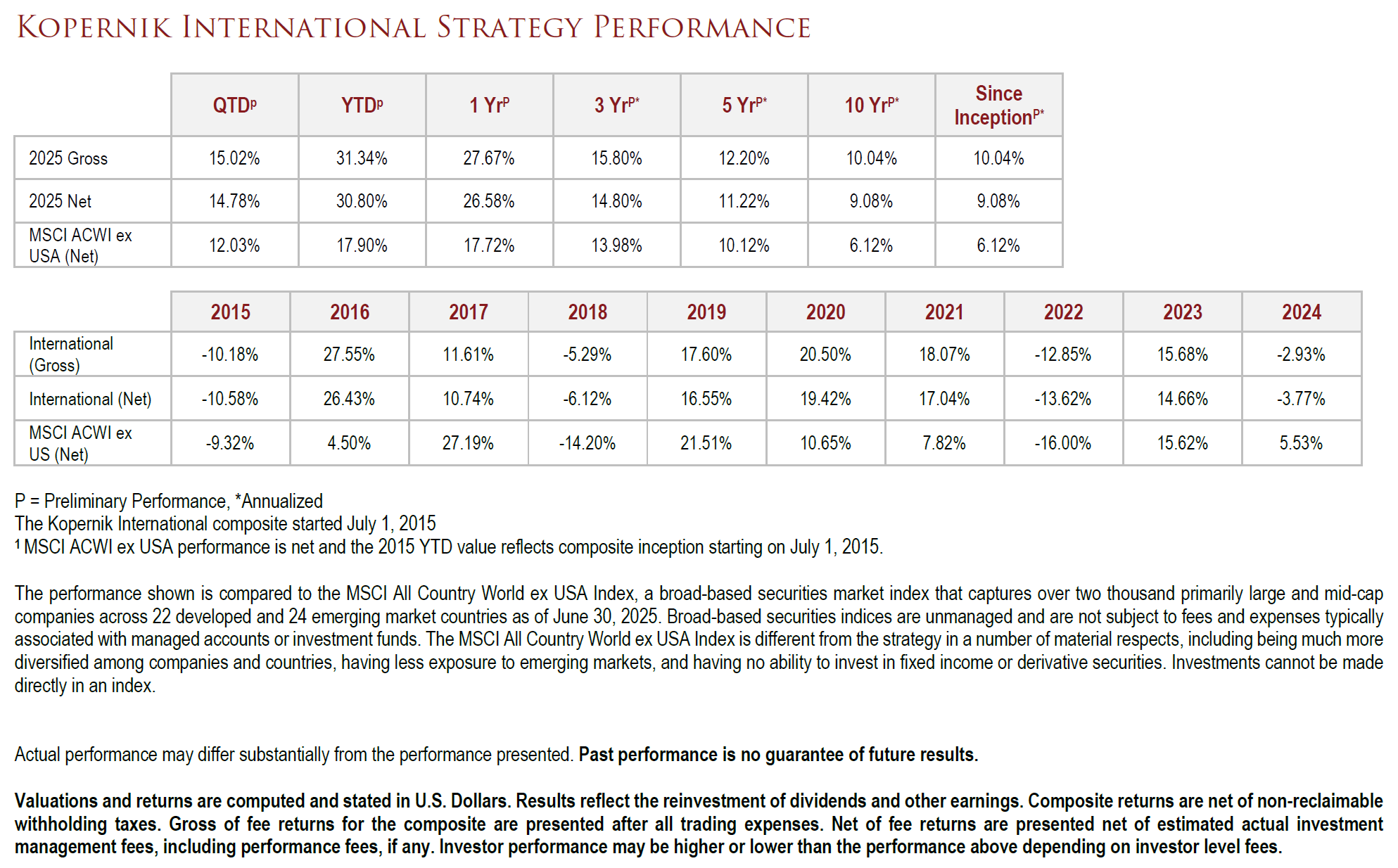

Overall, firm assets have continued to grow, and we ended the second quarter with roughly $7.7 billion under management [including Advisory Only assets of ~$200 million]. As a point of reference, we started the year with $5.3 billion. This growth in assets can be attributed to market action due to the strong performance across all our strategies, combined with close to $500 million in net new inflows. It truly is refreshing and encouraging to finally see an uptick in value as an investment style. We also see more clients and prospects reduce their U.S. weighting, or at least revisit it, and are seeking more opportunities overseas.

Moving along on the personnel side, we are now 47 employees strong, and we’ve had minimal turnover since the inception of the firm over 12 years ago. We continued to bolster our research team and other parts of the firm during the year. A couple of quick housekeeping items. Please note, you may recall we announced the soft close of our Global All-Cap Mutual Fund in the U.S. It’s scheduled for end of this coming month, so July 31st, please note that.

That being said, we are thrilled to have our International Fund just hit its 10-year anniversary. As you know, it’s managed with the same philosophy, process, and team, and hence the high degree of overlap and strong performance that the fund has. Also, we’re happy to mention our Global Long-Term Opportunity Strategy is right around $100 million. This is a crossover strategy and has been garnering a lot of interest, too. If anyone has any questions on any of these products, please contact us for more information.

Please note, Dave and Alissa will be referring to the presentation, which can be found on our website, kopernikglobal.com, under the News and Views section. Also, whilst on the website, you can also access Dave’s most recent commentary and several other pieces and interviews by the investment team, which have been well-received by the marketplace. This brings an end to the business update. With that, I’ll pass it over to Alissa. Alissa, please go ahead.

Alissa Corcoran: Thank you, Kassim. Before we get into the call, we wanted to make an exciting announcement that since our Super Terrific Happy Day was so super terrific and happy that we’re going to be hosting this again this [coming] year. However, this time it’s not going to be in the heart of hurricane season. This year [2026], the event will take place in February. Please mark your calendars for February 17, 2026.

All right, on with the show. The most common question we’ve received in recent weeks is, have we missed it? [slide 8]. Have we missed the opportunity with Kopernik? Our performance here today has been quite strong. The gold miners are up more than 50%. Emerging markets have handily beat the NASDAQ, the S&P, Magnificent Seven. The goal of the presentation is to really demonstrate that, no, investors have not missed the opportunity. The opportunity is still there.

We’ll show examples of how leading companies and entire countries are still trading at an attractive price on absolute basis and also huge discounts to the U.S. Speaking of the U.S, it’s surprising to us that no one is asking us if they have missed the S&P or the NASDAQ or if they’ve missed the Magnificent Seven. Inertia is, as we all know, a very powerful thing. But should they be asking that? We believe so.

Another point we’d like to make in this presentation is that leadership is not stagnant. There’s migration. Markets shift, sentiments shift. We saw how quickly sentiment can change from positive to negative in April [slide 9]. We also see how quickly investors can forget. The rally since Liberation Day is amongst some of the best rallies in history [slide 10]. Meme stocks are back, although with seemingly less staying power. We’re now close to all-time highs in the S&P and NASDAQ. What is the mood? We’d say optimistic, if not delusional.

Unsurprisingly, analysts have also become more optimistic, increasing their estimates of earnings as stock prices have risen [slide 11]. Earnings for the U.S. stocks are at all-time highs. Yes, there’s lots to be excited about [slide 12]. AI, no doubt, is transformational. Goldman Sachs says it will boost productivity by 1.5% a year. Some AI CEOs claim AI is going to cure cancer, will grow the economy 10% a year, all with a balanced budget. AI seems to be magical as well.

However, on the flip side, there are some major issues [slide 13]. The future is unlikely to be like the past. We continue to have tariff uncertainty with the possibility of reciprocal tariffs. We have two wars going on. Things are not improving in the Ukraine, and things have only escalated in the Middle East. We have a continued reversal of globalization. As Howard Marks mentioned, this is not a trade war, but a global economic divorce. Bond yields are rising globally, technology is changing by the day with the potential to disrupt the market darlings, and this idea of U.S. exceptionalism being questioned is a real thing. It’s been fascinating to see the difference when you were doing marketing trips in October and November, December last year versus today.

The market is shrugging all of this off. Further, it’s clear that the cutting of the budget deficit is not going to happen until we face a huge crisis [slide 14]. This page is already out of date. The Big Ugly Bill is big and ugly and will only add more to our deficit. Clearly, this is not just a U.S. problem, but a global problem as well [slide 15].

How do we navigate all of this uncertainty? [slide 16]. There’s a lot of suggestions from well-known, successful investors. Jeremy Grantham suggests owning high-quality companies with strong balance sheets outside of the U.S. These companies should be resilient to disruption. Russell Napier also suggests owning outside of the U.S. and goes even further by suggesting people take their money out of the U.S., out of fixed income, put it into safe haven assets. Putting it into safe haven hard assets seems to be the thing that everyone can agree with. Interestingly and importantly, not one of these investors say stay the course, which makes sense to us because leadership changes.

We’ve shown this slide before [slide 17]. The basic takeaway is that the winners of the previous decade are not the winners of the next decade. In the 1970s, you wanted to own gold and real assets, but you did not want to own gold and real assets in the 1980s. You wanted to have migrated to Japan. Again, you did not want to own Japan when it crashed in ‘89. You would have wanted to rotate and migrate into the NASDAQ. Here we are halfway through the decade, and gold and energy have done very well decade to date, but the S&P has also done well. It has not capitulated yet.

Markets are not stationary [slide 18]. As the best investors know, money migrates like birds, and there’s a German word I won’t even try to pronounce, which basically means migratory restlessness. Birds right before they migrate become notably restless, increasingly uncomfortable, their organs change. All of this encourages them to make the long journey South, and then they use magnetic fields as their guide to determine the direction.

Investors are not too dissimilar. High valuations eventually become restlessness, spur movement. We, value investors, don’t use magnets, but fundamental analysis and price as our navigational tools. And while we, value investors, have been restless and uncomfortable for many years, the majority of investors have seemed to recognize it was not time to migrate. It was not time to migrate in 2016. It was not time to migrate in 2020 and 2022. This time, though, the market restlessness is seemingly for real. People seem to be genuinely interested in value and active management. Things seem to be shifting.

The dollar is a good example [slide 19]. The dollar has been on a 15-year run, which is the longest since, if you go back to 1970. Perhaps the dollar is beginning to migrate south. Could we imagine migration from overvalued equities to undervalued equities? [slide 20]. As an example, you could buy the Magnificent Seven for nearly the same amount as you could buy every single company in the Morningstar Emerging Markets Index, and every single company in the MSCI ACWI Small Cap Index.

If you combine emerging markets and small caps, the EM (emerging markets) small caps are extremely undervalued. As you could see, it would not take a lot of money migrating from just global equities or Magnificent Seven into emerging markets small caps to have those move quite significantly. One could buy our fund, which is mostly a portfolio of market leaders and oligopolists, for less money than any single one of the Magnificent Seven companies.

Back to the question of, have investors missed it? [slide 21]. Emerging markets have underperformed for a decade and a half. This is not going to be reversed in a single quarter. It’s important to recognize that investors migrated away from emerging markets after an enormous rally in 2000 to 2007, when emerging markets were up almost 300% [slide 22]. The same story is true of small caps, which underperformed for 12 years [slide 23]. Again, this is after a very strong rally in 2000 to 2007, where they went up nearly 150% [slide 24].

Commodities have not been the place for much longer than both the emerging markets and the small caps [slide 25]. They’ve been underperforming since 2008. Again, like emerging markets and small caps, there was a monster rally before that with the China super cycle. They are so depressed now, that NVIDIA’s 8% weighting in the S&P is more than the energy, utility, and material sectors combined weighting [slide 26]. Technology makes up 34% of the weighting. The energy [MSCI World Energy Index1], the metals and mining materials index [MSCI World Metals and Mining Index2] are very depressed. We’re far away from the point where we were, say, in 1980, when energy and materials made up close to 40% of the index. There’s a lot of money that could flow into these areas, might some of the technology market cap migrate into the things that make them work. As you can see, the comparative market cap, not a lot of money needs to flow into these areas to make them move much higher.

We’ve seen big moves in commodities before [slide 27]. Oil in the 1970s went from $3 a barrel to $40, copper tripled, gold went from $35 to $800. Things can change. Leadership changes, money migrates. To dive deeper into some of these specific companies in our portfolio, I’ll turn it over to Dave.

Dave Iben: All right, thanks, Alissa, and hello to everybody. Thanks for joining us. Continue on to the same idea of, have we missed it? Because a lot of people are asking that. We’ll take that from several vantage points [slide 28]. First of all, we don’t know the future and nobody does, so we can’t perfectly answer the question, but we can look at history and we can look at logic. As we often do, let’s quote Charlie Munger, who says, “Show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcome.” We think the incentives suggest that this is the beginning of a long-term trend, not the end of a two-quarter trend.

If we go back to the 1970s, which is probably the last time that you’ve had an environment, we’ve talked about this in the past, 40 years of disinflation in relatively decent times. You’ve got to go back a long way to see times where we’ve had complete fiscal profligacy like we’ve had now. They called it the guns and butter in the ’60s. That incentivized people to own real assets, and that turned into a decade-long trend.

2% inflation has become a floor instead of a ceiling, and from something that wouldn’t even be considered in the past, that seems to incentivize malinvestment and speculation. We’ll see where that leads from here. Years of discouraging investment in energy and materials, that sowed the seed for big shortages back in the ’70s. It seems to be doing the same thing there. That’s not even counting the demand for AI and all those things you’re going to need to incentivize much higher prices to meet the demand for that. Massive disruption, we think, eventually, will incentivize people to migrate to the less investable areas.

Going from there, where are we now? That’s passive investing [slide 29]. Having lived through the ’90s and watched the ’70s, we do not believe an investment is good or bad. It is a cyclical phenomenon. The idea is, if markets are somewhat efficient, most people are working really hard doing the analysis required to make the market efficient. Few people invest passively, they get the free ride. It starts working, people fire their active manager who sells the cheap stocks. They put the money in the passive, which buys the index, which makes the index no longer representative of the market but more expensive. This continues until in 1999, and again now, even more so now. The stocks in the index are way more expensive than the stocks that are not in the index, so the whole efficient market theory breaks down.

Very few people are actually doing the analysis, and that’s a great time to do the analysis. We saw in ’99 when nobody could beat the index to the next seven years, where it was so easy to beat the index, how could you not? By 2007, people were paying 2% and 20% to hedge funds to not be like the index. Bad timing there because the index has done really well for a long time. We’re talking trillions of dollars that have been invested with disregard to quality and price of what they’re buying. That must revert to the mean at some point.

As Alissa already pointed out before, if you took 10% of the money that’s NVIDIA and Microsoft, you could buy, not our fund, but you could buy every company in our fund 100%. That’s the sort of thing that can happen. I know, after ’99, a very tough time for me as a value investor was followed by very good years in a market that was falling for three years. Our stocks went up for three years. That’s what happens when some of the market caps of the big companies start to come into more attractively valued. It can lead to very good things.

We could go on and on about how things could be like the ’70s, where when you incentivize these things to work, they went to things people couldn’t have imagined before the ’70s [slide 30]. People could not have imagined emerging markets doing that well, or gold going from $35 to $800, or oil going from $3 to $36. Those are the sort of things that could happen, but we don’t know the future. We’re not going there. We’re going to go with a much more modest way of looking at things.

What if things just go back to where they’ve already been? Yes, they should go much higher, but let’s be more modest. What if the euro, that’s had a nice move this year, gets back to where it was within the last couple of decades, or a one-third move? Here, in the UK, some of us have been doing research here. It’s getting more expensive with the pound going up, but to get to where the pound was a few years back, it’s got to go up another 54%. The Japanese yen; we’re talking some big moves. We are only beginning to get back to where things were.

Where should the currency of a country that’s running $2 trillion deficits during the good times be? Where should it be in the next recession when the deficits are at $3 trillion plus? A currency that’s gone straight up for 15, 20 years, it’s not hard to imagine that it could keep falling. There’s a lot of people that think Washington wants it to fall.

Turning to the next page here, stock markets [slide 31]. Some of these emerging markets and non-U.S. markets are off to a good start. They’ve had a good six months, but as Alissa pointed out, after almost two decades of underperforming, two quarters are a big thing. Korea has been one of the best so far this year, but just to get back to its 10-year high, another 31%. Hong Kong and China are both pretty amazing. They have a big upside to where they once were, but the Chinese index is well below—it’s a third lower or 25% lower than it was in 2007, despite the economy growing, I think, sixfold or something like that. A big upside.

Brazil is doing pretty well and well-positioned on commodities and things that are doing well. 64% potential upside. That’s not even to what could be. That’s just to what has been. If we look at things on a potential, if they were just to re-rate equal to the U.S [slide 32]. Six months ago, all that we heard about was U.S. exceptionalism. Now, almost everybody I talk to is questioning that saying, “Sure. It’s a great country, but is it that exceptional deserve these premiums?” Well, MSCI Asia has to almost triple to catch up to the U.S. in terms of valuation. China, more than triple. Even Japan, with a big move it’s had, it’s got a long way to go. Other than India, almost every market in the world can go up one, two, three, four times just to catch up to the U.S. in terms of valuation. Not saying it will. Just saying it could, and might say should.

This shows some of the emerging markets in particular and how much upside they have [slide 33]. There, again, the developed markets are at all-time highs as we speak, all-time highs. Yet, these emerging markets need to double and triple to get back up to where they once were.

Same thing with small caps [slide 34]. Small caps, when I came into the business and several times since then, people said small caps deserve to be at a premium because small can sustainably grow faster than large, a lot of large numbers. Not the case now. In order to get back to average, we’re talking a 40% jump. Get back to where people are liking them once again, 78%. We think that’s pretty good. Now, you’ll notice here, right about the time we started Kopernik, is when these things were their maximum premium to large stocks. It’s been a bad dozen years for small stocks. Now they have that kind of potential to pick things back up.

This, we’ve done in the past [slide 35]. It’s always interesting to psychologically see the way people look at things. People were really excited about Chinese technology a number of years ago. Not so much now. In the U.S., if you tell somebody here’s a company that’s good at AI and good at search and good at autonomous driving, they say that deserves to be very expensive. A similar company in China, not so much. Six times book [value] versus just over 0.6, 0.7. Fascinating divergence. You have to catch up to Google valuations. Whether it’s doubling or going up eight times, you tell me. That’s the sort of potential after the good half a year that emerging markets have had. Part of the reason some of us are here in the UK is because stocks are so cheap here after underperforming for a long, long time. We’ve been able to take advantage of some financials and some others.

Once again, cycles and changes in mood [slide 36]. 25 years ago, we would have been talking about TMT, tech, media, telecom mania. Telecom was all the rage. As it happens at the rage, the good companies do stupid things. Vodafone was doing lots of stupid things and highly loved. Just growth for growth stake and investing everywhere, and borrowing lots of money. The stocks have done miserably for a quarter century and deserved to do miserably. People bought it when they were doing the wrong thing. They are selling it as they’re doing the right thing. Now they [Vodafone] don’t want to be everywhere. They want to be good where they are. They’re buying or selling to make sure they have a good market share every place they’ve been. Verizon is a good company, arguably fairly valued. We were talking to you a year ago and two years ago about how KT [Corp] was Korea’s equivalent of Verizon and how you were paying 10 times as much per customer to own Verizon.

Since then, Verizon stock has done next to nothing. KT has gone from our biggest position to much smaller because of the huge run it’s finally getting around to having. Vodafone seems to be there now. Is Verizon worth nine times as much per customer? We think not. Time will tell. We like it when people are looking in their rear-view mirror and worrying about the last 25 years, when they maybe ought to look at what is happening now.

Hyundai Department Store, yes, department store’s in the name, but they’re mostly an owner of high-quality real estate that has malls and everything on it [slide 37]. Stock seemed to drop every single day. Then we blinked, and all of a sudden, it’s doing quite well. Even after doing quite well, you can see on this diagram that every few years, the stock prices converge and they’re the same. In order to converge once again, we’re talking a big move in the price of Hyundai Department Store. Lots of upside left [catching up to Simon Property’s] book value, maybe is extreme, but just catching up stock-wise, we see big potential [to get to Kopernik’s estimate of risk adjusted intrinsic value].

Auto parts and something that’s coming in and out of favor [slide 38]. But within auto parts, looking at emerging markets versus developed markets, and you see wider premium. Some of these ones in emerging markets, they’re located there, but they have plants in the U.S., they have plants all around the world, and developed world. They really are probably being misperceived as being in emerging markets. You can see, we expect to double our money and then some, just to catch up to the prices of similar developed market companies.

Agriculture is an interesting thing, it deserves to probably be at a discount in Indonesia versus Iowa, although they do have great growing conditions and good soil, and good companies [slide 39]. We’ve shown these things in the past, tremendous upside [compared to the price of Iowa land on slide 39]. Interesting, Ukraine, for obvious reasons, people have been avoiding that, but these companies have done quite well. Both stocks doing well, and the company is minting money, even with the problems there. Often, it’s best to pay more attention to the quality of the company you’re buying and just accept a big discount for the country they may happen to be in.

Here, we’ve got some charts showing just commodities in general [slide 40]. The grains were all the rage three years ago. Now they’re way cheaper than they were in 2007. That we think is interesting. Just to get back to where they were a few years ago, we’re talking 100%. We’re talking a world that now has 8 billion people in it, we’re talking $7 trillion has been printed, lots of money, lots of people. Yet the price of grains are cheaper than they were 20 years ago. We think 100% upside, there, is something that could happen. Some would say should happen.

Banks, for a lot of reasons, the big companies are the ones to look at, the dominant ones [slide 41]. Here, we have a very dominant bank in an emerging market [Halyk Savings Bank] versus JP Morgan that we all know. They both should do well. They’re both doing fine. Look at the [potential] upside that one gets on Halyk, and that’s after it’s gone up a lot, just to catch up to a JP Morgan. A couple of quarters of emerging markets doing well have not begun to make up for the underperformance of two decades.

Some of you remember, not long ago, we did a white paper on conglomerates [slide 42]. We’ve talked about how people just categorically don’t like conglomerates. They’ll tell you that. You can say, “Well, do you like Berkshire Hathaway?” They all agree. Yes, they do. Do you like GE? Yes. Do you like private equity? Yes. How about Honeywell? Yes. They probably should like all those. Those are fine. Once we’ve agreed that not all conglomerates are bad, maybe we should look at companies and look at them company by company, and pick the good ones. Here we’ve got a handful of good ones that own businesses that are growing book value consistently, making money pretty consistently, have a lot of management skin in the game, all the things you’re looking for. If they want to re-rate these conglomerates to a price similar to what they’re giving to Honeywell, we’re seeing doubling in price, we’re seeing possibly twenty-fold increases in price. We don’t think people have missed the conglomerates because they’ve just had a good quarter.

It’s interesting, five years ago, it wouldn’t have been easy for people to imagine that people would have gone from hating nuclear power to viewing it as the answer to a world that can have base load power that’s cheap and clean, and carbon-free [slide 43]. They’ve embraced it now. They like it. In the U.S., they love it. We’re talking Constellation: 32 times earnings, almost eight times book value. They love it. China has a company [CGN Power] that we would say is at least as good, probably better. The Chinese seem to be good at building these things very inexpensively, and thus far, has been high-quality. We’re talking about half the PE (price-to-earnings), we’re talking a small fraction of the book value, we’re talking going up four and a half times just to catch up to the price of Constellation. These are the things we like. Really good companies that maybe meet the needs of the world and are very mispriced.

Once again, we’re here in the UK, Schroeders has, for a long time, been viewed as a quality company, as has BlackRock [slide 44]. Look at the divergence here. Then it comes back to that passive-active thing. People are putting money into passive funds and ETFs, but they seem to be starting to revisit that. What if our industry is like every other industry on earth, where putting a lot of time and effort and hard work and thought into something actually deserves to sell at a premium versus mindlessness? As this cyclical phenomena peaks and starts to swing back, which might already be happening, active managers should start to see their performance be so much better than passive as to justify their fees many times over. If I’m wrong, the stock is too cheap anyhow.

Here we have health care pharmaceuticals [slide 45]. Famously, prices of health care are out of control in the U.S. Health care is good in the U.S., but way overpriced. People pay five, ten times as much for the exact same drug as they do from the same company in other countries. Should it be an industry that has lousy margins in Asia and extreme margins in the U.S.? Can that last? Is the whole UNH problem just the tip of the iceberg that’s turning people’s attention to this?

Alissa: Looks like, Dave, you cut out for just a second. Okay. It seems like you’re back now.

Dave: Anyhow, if things can even out, there’s big upside, but if not, we think there’s a reversion in the mean of the stocks anyhow. Then there is the whole idea of commodities in general [slide 46]. People are starting to notice commodities again, but not really. You’ve got many commodities trading lower than they were in 2007, and you have financial assets and the Dow Jones and everything else at all-time highs. Usually in a world that’s filled with uncertainty and unknowns and wars and interest rates and inflation picking up, it’s an odd time to see financial assets trading at an all-time record relative to real assets. One would be expecting the opposite. If things get back to more average, we’re talking a triple in real assets. If they go all the way back to more extreme levels, like happened in the ’70s, then we’re talking an eightfold-increase potential.

Commodities are good, but as we’ve talked about, commodities in the ground are something else [slide 47]. The mining industry gets no respect. Half of that might be earned, but the other half is not. These are scarce and needed. When I came into the business, materials were 20% of the index, energy was 30% of the index. We’re talking half the index in commodities, and how weird that they’re now a single-digit part of the index, just as they’re needed. They’re needed for AI, for data warehouses, for electric vehicles, for windmills, for solar farms, all these things. The world that people are paying massive premiums for is a world that needs materials. What an odd time for mining to be trading at such a discount.

With gold in particular, as you know, we’re a lot less excited about gold at $3,400 than we were at $1,050 a few years back [slide 48]. Gold underground still trades at a massive discount to gold above ground. The upside is a double, if not a four-fold increase, just to catch up to what things looked like in the past. Because mining tends to be a very operationally levered business, a big increase in gold should be followed with a bigger increase in mining stocks. Gold we like versus the dollar, but we don’t like it versus gold mining stocks. They’re too cheap.

To continue on this theme, and we’ve talked about this in the past [slide 49]. Nickel is really cheap versus gold. People loved nickel because of batteries and whatnot. Now they don’t like it at all. Copper, we go to this really big, well-known conference on mining every year, BMO puts on in South Florida. A few years back, 95% of the people said copper was their favorite. Since then, you can see gold has left copper in the dust. Copper is pretty interesting again now. Iron ore, once again, is very cheap relative to gold. We’re taking advantage of that.

Oil has gone nowhere for decades [slide 50]. While gold is at new highs, oil becomes interesting. Uranium it has its spikes that you can see here. The time to buy was a few years ago, but now we’ve got a spike that makes it the third-best time ever to buy uranium relative to gold. We think that bears paying attention to.

Silver is starting to run, but still very inexpensive relative to gold [slide 51]. We see a lot of potential there. Platinum, I think last time we talked, we were wondering why it was at $800 when it used to sell at the same price as gold [slide 52]. It’s not at $1,800; it’s $1,400-something now, but it still ought to catch up with gold someday. It’s usually sold at a premium. You can see here it’s a lot more scarce than gold is, and it has all the same good qualities, scarcity, divisibility, non-corruptibility, whatnot. We continue to see lots of [potential] upside there.

Then, what is this? [slide 53]. Man, we have a quarter where, in early April, because of tariffs and uncertainty, the market was in a panic and falling. Now, because of tariffs and uncertainty, the market’s screaming up to new highs every single day. Those are the sort of things you want to take advantage of as an investor, and that’s what we’ve been doing. You can see, when the market was falling, we were able to buy lots of companies and lots of industries. You can see, two quarters later, we were finding much more things to trim than we were to buy.

It’s important to note that some of the things we were able to buy in April, we were trimming in June. That’s how fast some of the things got up. Also, we just talked, with some slides, about how gold might be good, but other things are better. You’ll notice within the resource areas, things that used to be too expensive for us, are not. The diversified miners, we were able to buy Glencore [PLC]. We were able to buy Vale [SA]. The copper that we’d sold earlier, we were able to buy back, whether it’s Lundin [Mining Corp] or Ivanhoe [Mines Ltd], at way cheaper prices than what we sold. Those are interesting.

We didn’t buy much gold, but we did have a chance to buy Novagold [Resources Inc]. It was an opportunistic chance to take advantage of a transaction that increased the likelihood that Novagold’s mine gets built. That, we find interesting. Some of the depressed investment companies we were able to buy we’re trimming a couple of quarters later. That’s how quickly they went up. You can see volatility has been a friend of the fund. It’s given you all a chance to make some money on quick changes in the attitudes of the crowds.

We’ve talked about the valuations with the market at all-time highs [slide 54]. This portfolio has a book value of less than one, tangible about one, ridiculously cheap on enterprise value to sales and cash flows, and what not. Importantly, that is not based on, for the most part, deep value. It tends to be oligopolous [slide 56]. You can see at the upper right-hand corner, your portfolio has the number one platinum miner [Valterra Platinum Ltd, previously known as Anglo American Platinum], a tripolist phone company [LG Uplus Corp], the number two platinum miner [Impala Platinum Holdings Ltd], the number one uranium miner [NAC Kazatomprom JSC], the number two undeveloped copper/gold property in the world [Seabridge Gold Inc]. One of the largest palm oil producers in the world [Golden Agri-Resources Ltd]. One of the best low-cost, high-duration natural gas with Range petroleum [Range Resources Corp]. One of a handful of good fertilizer companies [K+S AG]. The number one gold company [Newmont Corp] and a big conglomerate [CK Hutchison Holdings Ltd]. These are the sort of things that we’re able to buy for, on average, less than one times book.

That has us feeling like we’ve missed very little, that there’s much more in front of us [slide 58]. The data suggests that they’ve not missed much, that they’re starting to rotate from expensive stuff into attractive securities. History and valuations show that these are long-term trends. We showed you a lot of charts. These tend to be generational trends. We don’t think that two quarters is a generational trend. Also, we can argue that scarce things that are needed and economies that are growing should reach new, relative high valuations. We showed you what if they catch up to where they were. A case can be made they will do much better than that. If things revert, just to recap what we’ve already told you, small caps have a long way to go. Emerging markets have a much further way to go. Miners relative to the minerals they hold, a much better place to go. Our portfolio, after having a nice first half, it’s worth more than two times what it’s selling at, according to our analysts’ risk-adjusted numbers.

We will leave you with the idea that when you have this upside, people should spend less time worrying about the news and looking for catalysts, and worry about what they caught or missed [slide 59]. Think about those returns. Make it worth being patient. Own good, scarce, high-quality things. If they double soon, we’ll all be happy. If it takes a few years, we’ll still be pretty happy. We’re hoping this will be, like the last time after the late ’90s, when the run into value was a 7- to 10-year run. We don’t know, but things seem to position quite well. With that, we look forward to answering your questions.

Mary: All right. Thanks, Dave. Thanks, Alissa, for another great presentation. Before we get started, let me just briefly share a quick comment about our methodology for handling questions. We’re so thankful to each of you for your attendance and all of your questions. To keep the session flowing and be sensitive of everyone’s time, I’m going to group similar questions together thematically as I moderate the discussion. I may or may not read each question individually. If you feel as though your question has not been addressed, please absolutely reach out to us after the call. We’re more than happy to follow up with you.

We’re actually going to start with a couple of questions that came in prior to the call. One of them is about gold. We’re going to talk a lot about gold in these Q&A, if this is any indication of what I’m seeing so far. Does the team believe that the rise of stablecoins and cryptocurrencies will impact the demand or price of gold, which has historically been considered a safe haven asset during times of currency volatility and market downturns? Alissa?

Alissa: I think that, as we’ve shown, mining gold, it’s a very small part of the global market cap in debt, in money, in equities. I think that if people like cryptocurrency, maybe they store their value there. We’ve seen that cryptocurrency has a high beta. It seems to follow the U.S. index. I’m not so sure it’s a safe haven. Gold certainly is a safe haven, and it’s time-tested. We are not so sure about cryptocurrencies. You are now trusting an algorithm. Long way of saying that there’s room for both. Gold is time-tested, and central banks have been buying 30% of the mine supply. That’s basically since 2022. Central banks continue to buy gold. They seem to be preferring gold to cryptocurrency.

Either way, as our chart showed [slide 48], even if gold goes nowhere, the miners have huge [potential] upside just reverting to an average of gold miners to the gold price. That’s what we’re really excited about. Gold miners as a percentage of our portfolio has dropped significantly. It used to be 25% of our portfolio. It’s now down to 12%. Those charts [slides 49 & 50] showed that iron ore and copper and nickel, and oil, those are the commodities that are much more attractively priced to gold. We’re seeing that in the producers as well. Dave, do you have anything to add to that?

Dave: No, I think you put it pretty well. I think that the competition in a world of huge deficits in most countries around the world, people they can argue about whether they should own more crypto or more gold or more copper, or more land, or whatever. They definitely should be considering all those things as opposed to sitting in cash for the long term. Cash is good optionality in the short run, but it is not something people want to hold long run. Even Warren Buffett is saying that.

Mary: Our next question, Dave, I’m going to throw this one to you. You mentioned several times that a bunch of us have been in London this summer doing some research. We have a question that is, what’s your main takeaway from your time in the UK this year?

Dave: People might be aware that this is our ninth year of doing this. We’re a global firm, and in the U.S., it’s sometimes good to get out of that U.S. framework and see the world and see which stereotypes are true and which aren’t. Many of them aren’t. We were fortunate enough to, say, be in Canada looking at resource companies before they got really cheap during COVID and to be in Argentina when things were starting to open up there. Korea last year, a side trip from Japan, before Korea’s off to a good start this year.

The UK, one, the stocks have been underperforming for a long time. Two, you start hearing about brain drain, and nobody wants to live here anymore. It’s dangerous. It’s not what it once was. We are finding that it’s what people used to think. It is a cultural haven with lots of smart people from all over the world, a lot of vibrance and culture and arts, and great businesses. People complain about the politics here, like they do in every other country. They’re right to worry about it here as they are in every other country. There are problems, but smart people, good businesses, a lot to offer, and good prices.

We think, once again, the timing’s been okay. I talked about Vodafone a little bit. That’s been a good opportunity. We’ve already been able to make some money in some of these depressed money managers. We’re looking at some industrials and other things. It shouldn’t be surprising to see if we find more opportunities here. We find things are much better here than the general stereotypes we are hearing about in the U.S.

Mary: It’s always nice to leave Tampa in the summer for somewhere a little bit cooler.

Dave: That doesn’t hurt.

Mary: All right. Thank you, Dave and Alissa, for your answers to those questions. Our next question is from a lot of people. We have about four different iterations of this same question, so I’m just going to ask it in the most general way possible: to please comment on Northern Dynasty. Dave?

Dave: Certainly. Northern Dynasty is one of those things that’s always interesting to us. As how Warren Buffett put it, if you can find a really, really good business with some short-term solvable problems, that’s often a great investment. What would be a really good asset to have in this world? The world needs copper. The world wants copper. There’s a shortage of copper. The U.S. in particular has decided it’s a critical mineral right now, and the U.S. doesn’t have that much of it.

With COVID, they realized they wanted local supply. The biggest undeveloped copper and gold property in the world happens to be in the U.S. That’s the sort of thing that would be interesting to own. This property, as a lot of you know, there was a very rich guy. He’s no longer with us, but when he was alive, he made it his mission to stop this mine from being developed, gave lots and lots of money to people to try to stop it. A lot of misinformation was spread out about it. Their NGOs are still spreading information about a mine plan from years ago and disregarding the one that the Army Corps of Engineers looked at and said no harm to the environment. It’s a good plan.

With politics, it’s gone back and forth. This is not something that’s going to get built tomorrow. The world doesn’t like uncertainty. They don’t like patience. Because of that, we’re able to get one of the best mining properties on the earth for next to a song. We have some common stock in most of the funds, and we have one strategy that has a royalty on the property.

There’s a long way to go. It’s a lot of politics involved, and when it’s all said and done, I think a certain amount of the economics needs to be figuring out how much is going to go to the local peoples and how much to the government and which major players are going to come in and make this happen because Northern Dynasty would be the first to tell you they’re not going to do it themselves. They’re looking to partner with somebody big. This requires lots of patience, and it’s going to be a long-term thing. It’s possibly worth 100 times or more what it’s selling at, so it’s something that deserves a place in every portfolio, we believe.

Mary: All right, we’re going to actually continue…We have several questions about non-producing gold miners. Alissa, I’ll throw this one to you. We have a question about our thoughts on Seabridge and any update that we might know or have there.

Alissa: No update. I guess it’s the same as with Northern Dynasty. It requires a lot of patience, but like Northern Dynasty, you have a huge asset, both copper and gold. You’ve had a management team that has, unlike Northern Dynasty, increased gold ounces per share. But like Northern Dynasty, it needs a lot of capital to build this project. We showed gold miners versus gold, but if we continued with what we’ve shown in the past, which is non-producers versus producers, the disconnect is very, very large.

Seabridge, as an example, has 1/2 the reserves as Barrick [Mining], but 1/23rd the market cap. There’s a very, very big disconnect in the market between these non-producers and the producers, which is something we think should be taken advantage of and deserves to be part of the portfolio. We also believe that these big mining companies, as they mine, they’re depleting their reserves. They’re going to need to replace those reserves. The success rate of finding gold is very, very small.

As the bull market builds, what you’ll find is that these big mining companies are going to rush to replace their reserves. We think it’s quite likely that they would be acquiring some of these smaller companies. It’s this match made in heaven because the smaller companies don’t have the operational expertise to actually build a mine and operate a mine, but they have the reserves. Meanwhile, the producers need the reserves, but they have all the operational expertise and the ability to get capital.

Mary: That relationship that you described between the producers and the non-producers, do we have a preference as to which one we prefer to own?

Alissa: It’s all about risk and reward. The non-producer obviously has more risk, so we require a much larger margin of safety, but at these disconnects, there’s much more [potential] upside in the non-producers. I just used the example of Barrick and Seabridge. We also own Barrick.

Mary: Right, exactly.

Dave: If I can add to that, it’s one thing what we think, more importantly, is what the market thinks. The best thing in resources is long-life reserves. They all use a model that’s upside down, and the models the whole industry uses, make long-life reserves worth nothing. This is something we’ve taken advantage of in uranium and natural gas and gold and copper, and you name it. That’s what we’re talking about here. Massive mispricings. The market hates long-life reserves. We are taking advantage of that. I could bore you guys for an hour on why that is, but look at our website or give us a call if you’re interested.

Mary: All right. We have another couple of company-specific questions in the metal space. Bear Creek, Dave, I’ll throw that one to you. The specific question on Bear Creek [Mining Corporation] is, do you think that illiquid assets like Corani are becoming more liquid with prices rising?

Dave: The comment I just gave about the market not liking long-life reserves, Corani is not going to get built tomorrow. It’s not going to get built next year. People don’t like long-life reserves, and this one’s way up in the mountains and very complicated. I think people give it no value. It certainly has some value. That’s a company where management has continually disappointed us over the years and lost value elsewhere outside of Corani. We would have rather they just focused on that. That’s a property somebody’s going to make a lot of money on someday, we believe.

Mary: Our final metal-specific question, Alissa, why don’t you comment on Perpetua Resources?

Alissa: Perpetua has had a tremendous run. It’s a mine in the U.S. In addition to gold, it also had antimony, which is important for defense purposes. It benefited from the administration’s push towards developing assets in the U.S. Again, you want to buy mining companies when nobody believes they’re going to be developed, sell them on the optimism. We’ve taken advantage of the volatility in that, and we are now no longer owners of that company.

Mary: We have one more question in the gold and precious metals space. Do you have concern that the low current level of proved reserves of gold, so the low level of proved reserves, relative to the above-ground gold, will result in higher mining costs, thus justifying the relative price difference of gold above and below the ground?

Mary: Dave?

Dave: Sure. There’s a whole lot of different things in there. Unlike most any other commodity, gold is not that much consumed. Yes, there’s a huge above-ground concern, which means supply doesn’t matter very much, what matters is demand. Whether monetary demand keeps picking up, or jewelry comes back, that’s going to be what matters. Right now, monetary demand’s picking up. That’s what’s driving it. I think the increase in price is less to do with above-ground versus below-ground. What matters is, we’ve talked a lot about how money turnings inflationary and prices have gone up. I think most of us have noticed that almost everything is more expensive than it was a half dozen years ago. If you’re in the mining business, you have to pay more for insurance, and more for labor, and more for energy, and more for your equipment, and that will continue. Then that’s compounded, and this is somewhat related to the amount of proven reserves, but mostly it’s the grade of the reserves.

You move a ton of earth, hoping to get eight grams out of it, and then three years later, you spend the exact same efforts moving a ton of earth to get four grams out of it, and then later you move it all to get two grams out of it. That’s what makes costs go up more than anything else. That becomes important. Keep in mind, some of the cost is having just bought the land, which people did years ago. If the cost of mining goes up by 400, but the price of gold goes up by 1,000, your profits actually are much higher. These guys, many of them are starting to make really good cash flow right now. Yes, the increase of costs have justified some lagging, and management missteps have caused some lagging, but mostly, I think the stocks are just too cheap relative to gold and are catching up and need to catch up, will continue to catch up. Gold’s been doing better than the cost of mining.

Mary: Thanks, Dave. We’ve got quite a few questions still. If you have any questions, again, please type them into the Q&A box. Alissa, we have a question about our thesis on offshore drillers, if you could comment on those.

Alissa: Yes, we’ve been looking at them for a while now. We’ve recently bought one. The offshore drilling space is a terrible industry. Almost all of them have gone bankrupt. Now, the ones that had gone bankrupt are actually in a much better position because they now have a stronger balance sheet. The ones that barely made it have some very good [potential] upside, and so we’ve been looking into them. Now oil is at $65 or so, and we think that fossil fuels are not going away.

The CapEx in oil is down considerably from its peak. Really, the CapEx is down since 2014. We think that eventually oil companies are going to need to spend more CapEx, and they’re going to need to spend it in offshore areas because one thing that has helped supply of fossil fuels has been the shale in the U.S. With all of the U.S. supply, now the supply growth is starting to stagnate. We think the new supply is going to have to come from offshore drillers, and these drilling companies are very inexpensive right now.

Mary: Thank you. Dave, next one for you in the popcorn round of sector and company-specific questions. Can you talk about our thinking behind Cresud and BrazilAgro [Companhia Brasileira de Propriedades Agricolas]? Someone was really interested in those agricultural investments in Latin America.

Dave: Let’s start with agriculture in general. We showed that slide showing the price of grains is pretty low right now. That doesn’t seem sustainable. As we point out early, more people, more money, prices higher in general, prices should go up. A question on Latin America, we’ll get back to that, but we like the fact that it’s a big world. We have agricultural companies in the Ukraine and in Indonesia and in Malaysia and in Brazil, and Argentina. It’s interesting, when the war broke out in Ukraine, we lost money on those two stocks, but the rest of them around the world ran up. That’s when prices went up so much. We trimmed that, bought more Ukraine. Now, Ukrainian stocks are doing really, really well, and some of these other ones have been weaker. We’ve been able to buy that. Diversification’s good.

Because agriculture has been lagging, we think agricultural stocks are too cheap. You’ll notice there’s quite a few of them in the portfolio. Argentina, it’s been a basket case for 100 years. Who knows what happens from here? We were there a couple summers ago. Pretty good timing, I think. Maybe [Javier] Milei can keep doing the things he’s trying to do. The two-currency system is disaster for their agricultural companies. Their farmers are starving, and yet the prices they can get exporting, it doesn’t make sense for people to buy. It’s been awful business. Maybe that’s changing. If that changes, the [potential] upside is tremendous. Argentina and Ukraine, and the U.S., they’re generally considered the three best places in the world in terms of quality, top soil, and a good climate with decent water. These are the places you want to own, and they own a lot of the good stuff. We like it on its own, but if Milei’s changes go through, we like it a lot more.

Then Cresud also has a real estate arm, and they have some of the best real estate in Argentina. There again, if anything can go right from that economy, there’s pretty good [potential] upside. We like it a lot. The important thing is to view Cresud as one of a half dozen companies or more around the world that are good and expensive ag companies. We expect to do well on the portfolio. Hopefully, Cresud is one of the ones that does well, but we think the portfolio should do well. It’s undervalued compared to the fundamentals of the world.

Mary: Alissa, a question about the thoughts behind adding to Carrefour, especially what do you think of the current activist campaigns and any outcome that might have on the operational performance?

Alissa: With volatility, we were always trimming and adding. With Carrefour, when it’s falling, we would be adding, and when it’s rising, we’ll be trimming. That’s just the way that we operate all of our positions in the portfolio. I’m not as familiar with all the activist campaign, but the reason we like Carrefour is that it’s the number one in France, the number one in Brazil, and the management has increased their position in Brazil because of a fairly good acquisition.

When you’re buying retail companies, you want to own scale because the barriers to entry to retail are very, very low. That’s one of the reasons we’ve liked Carrefour and the fact that it’s been an international stock and as a result neglected because it’s not in the U.S., it’s trading very inexpensively, less than book value.

Dave, have you been following the activist campaign?

Dave: No, not a lot. I will add it’s interesting. I was reading, I think on the Bloomberg a couple hours ago about Amazon’s prime day not going so well because they’re losing customers to Walmart. Who would have expected that? Then we’re talking a lot of us being in Europe right now because people cannot imagine good things happening to Europe anymore than they could have imagined good things to Walmart a few years ago.

We think that Carrefour like Vodafone and others, after years of not being very good at what they’re doing, are taking advantage of having great franchises and starting to do some of the right things. Yes, campaigns and activists and politics in France and other things will always be a headwind, but we think they’re a pretty good franchise at really good valuations.

Mary: Alissa, I’m glad you described in detail there are trimming and adding process because we’re about to move into several questions about our process. That’s actually the first one, is our thoughts behind how we trim. As we know, it’s based on price. The question is, if the value of the stock is far from what you estimate the risk-adjusted value to be, under what condition do you trim? By how much do you trim? How do you make those decisions?

Alissa: If we’re happy owning a 3% position in a company that’s trading at $10 a share, and let’s just pretend that we think the company’s worth $40. Even if at $15, the stock will have appreciated 50%, and it still has a huge amount of upside to the $40, we will still trim because we have seen that stocks obviously do not go up in a straight line. Volatility is our friend. If we were comfortable at 3%, at $15, we don’t want to own more than 3%. We either want to own 3% or potentially even less than 3%.

That’s the way we approach it. If you look at some of these companies or areas like uranium, where we had to wait eight years, or gold, even longer, the volatility allowed us to be very patient and also create good returns even when the stocks were bouncing around a lot. If you looked over a long period of time, they didn’t go anywhere. That’s how we’ve approached it. One scenario where we may not reduce the position is if the company is a pretty illiquid or small company to begin with, and we could only build a smaller position initially and it doubled, we still may not reduce the position back to the original model weight.

Mary: Those trims and adds sometimes lead to high cash balances, right? Because they’re a residual of our process of active management. We do have a question on our current cash balances, which are a little bit higher.

Alissa: Yes. In markets, when we’re getting a lot of questions about cash, it’s usually bull markets. Because our trims are getting done either faster than our adds, or because we’re not finding as many things to add to it. Like today where we’ve had one of the largest market rallies in history, we’re trimming a lot more things than we’re adding to. Therefore, our cash balances would grow quite naturally. It’s just a residual of the process. We don’t have a target for cash. We do like having cash because it’s an incredible option. It’s an option on volatility, which we think is not going to go away soon. We highlighted all the things that are uncertain in the market today.

Mary: Dave, I’m going to throw this next one to you. It’s a question on thoughts about businesses with negative working capital as value investments in higher interest rate regimes. The example that’s given is Warren Buffett’s Sirius XM investment, I guess Berkshire now owns ~34% of the company.

Dave: Oh, I guess I would need to know a lot more facts than that, right? High-interest rate environment, we haven’t had since the 1980s, so I don’t know what to make of that. If we actually had high interest rates, then I guess if you can get away with financing yourself with working capital, then why not? Then there’s risk that you can’t do that forever. It would depend on what kind of business it is, what interest rates are, and what the long-term plan is. So, I will duck that question.

Mary: We have a couple of other questions on research process. Alissa, I’m going to throw this one to you because, as the Director of Research. Both of you interact with our analyst team on a daily basis, so you know how they go about doing these things. The question is, when you invest in non-English speaking countries, do most of the companies have English version reports, or do you have to translate them? Is it a challenge to have a deep understanding of those companies’ operations?

Alissa: It’s a mix. Many companies will provide English financials, but some don’t. We’re very lucky that we have Google Translate. We also speak with the management team, and we speak with other companies. Our analysts are sector specialists. They’re not new to these industries. They have a knowledge base that translates from one country to another.

The thing is in investing, you’re never going to know all the answers. You do the best you can with uncertainty. The investors who demand certainty, a) they won’t ever have that, but b) they’re going to miss out on a lot of opportunities. One thing that we do is when we lack some information, we demand a much larger margin of safety, and we won’t invest if the information we’re lacking is material.

Mary: This is a second question that’s a part of this, which is, do you get most of the information from these maybe EM companies, or is there robust and consistent reporting?

Alissa: Yes, I would say there’s very good reporting. In some cases, the reporting is better than what you can find in the U.S. They may have 300 pages in the annual report, but not give you the disclosures on debt terms. The things that you need, that’s also part of the job, is really being able to focus on what things are material and getting those answers no matter, maybe they’re in the filings, but maybe there’s other ways of getting the answers you need.

Dave: I’ll throw in there, one thing we like to talk about is this concept of market efficiency, which we think is a ridiculous assumption. Is it tougher to deal with foreign languages? Yes. Is it tougher to deal with foreign accounting? Yes. Is it tougher to deal with conglomerate accounting? Yes. EM rules and this and that. The tougher it is, we don’t like that it’s tough, but we love the fact that we have less competition because a lot of competitors won’t do that. We think the mispricing is greater on some of these companies where we have these problems.

Mary: One last question on process. Alissa, I’m going to throw this one again to you because I get the privilege of reading all of the answers that you give to almost everything when we do stuff as part of my role. You recently answered a question about growth by saying that for us, value is a prerequisite, growth is a wonderful characteristic. The question is, how do you factor growth into valuations?

Alissa: Normally, we don’t. Most of the time we’re assuming no growth, and if we get growth, that is a wonderful thing. There are some times when we will say, you know what, this is a growing company and maybe should be valued appropriately. For example, we’ve in the past valued Sprott on potential. We said, okay, first on an EV (enterprise value) to AUM, they were very cheap using the current AUM, but they also had some brand recognition that would attract a gold investor.

We also were at the time very positive on gold. We looked at different scenarios and included those scenarios into our evaluation of, if the gold price rose, and therefore their AUM and their gold products rose, what could the potential be, and using a proper multiple on AUM, what are the potential upside could be? The important thing when you’re doing that is, what is your downside if you’re wrong, what is the downside to the current AUM. All of that looked very attractive in very limited downside, upside to the current AUM, upside to even the potential. We do factor in the potential growth, at times, when it’s appropriate.

Mary: Our last question, and Dave, I’m going to throw this one to you. It is a not hypothetical, but a philosophical question. What is more likely, overvalued assets declining or undervalued assets improving?

Dave: One last thing on the last comment, too, we as value guys don’t put a lot of faith in the future, but every now and then, if something’s clearly growing, it’s a simple like Gordon Growth Model. If something’s going to grow 2% a year versus zero, a PE of 25 instead of 18, that’s worth almost 50% more. There’s been a few times we’ve done that.

If the question is long-term, I guess I would say both are going to happen, or at least intermediate term. The undervalued things given time are highly, highly likely to go up. Overvalued ones are going to come down, but they could come down in real terms or by not dropping, but inflation catches up, or they could come down in nominal terms at some point that probably happens. The fundamentals we talked about how things look so much like they did in the ’60s and ’70s, we’re hopeful it’s like that, where value stocks went up in the ’70s. We’re hopeful it’s like after 1999, when our stocks went up every year when the market was falling.

We’re hopeful that it’s a rotation out of ridiculously priced stocks into cheap things, and so you get both. There’s a chance it’s a 1929, and we’re wrong, and everything comes down. For a lot of reasons, I would say both. I would say it’s quite likely you get, like you saw, after the ’60s and after ’99, you see some of the money leak out of these $4 trillion market caps. Just a little bit of that money can move some stocks up a long way. I don’t know the future, but my guess is both will happen.

Mary: All right. That does it for our questions today. Dave, Alissa, any concluding thoughts from you all?

Dave: Not a lot. It promises to continue to be an interesting year. We look forward to talking to you all again in three months, if not before.

Alissa: Thank you.

Mary: All right. Thank you for joining us. Have a great evening, everyone.

1The MSCI World Energy Index is designed to capture the large and mid cap segments across 23 Developed Markets (DM) countries. All securities in the index are classified in the Energy sector as per the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®).

2The MSCI World Metals and Mining Index is composed of large and mid cap stocks across 23 Developed Markets (DM) countries. All securities in the index are classified in the Metals & Mining industry (within the Materials sector) according to the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®).

The commentary represents the opinion of Kopernik Global Investors, LLC as of July 24, 2025, and is subject to change based on market and other conditions. Dave Iben is the managing member, founder, and chairman of the Board of Directors of Kopernik Global Investors. He serves as chairman of the Investment Committee, lead portfolio manager of the Kopernik Global All-Cap and Kopernik Global Unconstrained strategies, and co-portfolio manager of the Kopernik Global Long-Term Opportunities strategy and the Kopernik International strategies. These materials are provided for informational purposes only. These opinions are not intended to be a forecast of future events, a guarantee of future results, or investment advice. These materials, Dave Iben’s and Alissa Corcoran’s commentaries, include references to other points in time throughout Dave’s over 43-year investment career (including predecessor firms) and does not always represent holdings of Kopernik portfolios since its July 1, 2013, inception. Information contained in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but the accuracy of this information cannot be guaranteed. The views expressed herein may change at any time subsequent to the date of issue. The information provided is not to be construed as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any investment or security.

The Global Industry Classification Standard (“GICS”) was developed by and is the exclusive property and a service mark of MSCI Inc. (“MSCI”) and Standard & Poor’s, a division of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“S&P”) and is licensed for use by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. Neither MSCI, S&P nor any third party involved in making or compiling the GICS or any GICS classifications makes any express or implied warranties or representations with respect to such standard or classification (or the results to be obtained by the use thereof), and all such parties hereby expressly disclaim all warranties of originality, accuracy, completeness, merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to any of such standard or classification. Without limiting any of the foregoing, in no event shall MSCI, S&P, any of their affiliates or any third party involved in making or compiling the GICS or any GICS classifications have any liability for any direct, indirect, special, punitive, consequential or any other damages (including lost profits) even if notified of the possibility of such damages.