Proud Mary (Mar 2023)

In the early 1970s, my favorite band was CCR (Creedence Clearwater Revival). Great beat, excellent guitar work, I like the vocals, and there was so much imagery: Have You Ever Seen The Rain (coming down on sunny days), Who’ll Stop the Rain, Green River, Run Through the Jungle, It Came Out of the Sky, Bootleg, and Down on the Corner. Most of the songs were written by their front man John Fogerty, but they had some great covers as well: Cotton Fields, Heard it Through the Grapevine, I Put a Spell on You, and of course – Suzie Q, their first big hit. Reaching #11, it is CCR’s only top 40 hit that wasn’t written by Fogerty. They shockingly never had a number one hit despite five that reached number two on the charts, including our title song – Proud Mary. Per Biography.com, the day that John Fogerty received his discharge papers from the Army, in a celebratory mood, he began strumming the guitar and his blues-rock anthem was born.

“’Left a good job in the city’ and then several good lines came out of me immediately. I had the chord changes, the minor chord where it says, ‘Big wheel keep on turnin’/Proud Mary keep on burnin,’” Fogerty recalls in Bad Moon Rising: The Unofficial History of Creedence Clearwater Revival by Hank Bordowitz. “By the time I hit ‘Rolling, rolling, rolling on the river,’ I knew I had written my best song. It vibrated inside me.” Released in early 1969, the song peaked at No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

“Rolling, rolling, rolling on the river” came to mind the other day as the Federal Reserve reversed course and resumed, figuratively, pouring a deluge of money into the teeming river of monetary liquidity. Welcome to the latest in our series of commentaries discussing the importance of the Cantillon Effect. We find it instructive for those seeking to understand the current environment and navigate the turbulent waters of the investment world.

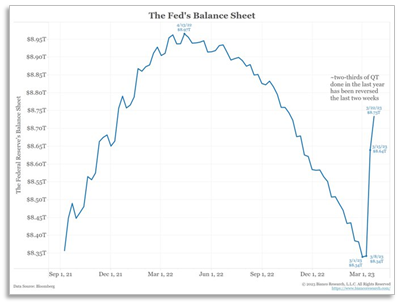

In case anyone missed it, in response to the Silicon Valley Bank debacle (and the expectations that it is far from an isolated event), two-thirds of the prior year’s QT (quantitative tightening/reduction of the money supply) was reinflated in a mere two weeks. We are now less than $300bn from recapturing the all-time, enormously high level of peak supply of money.

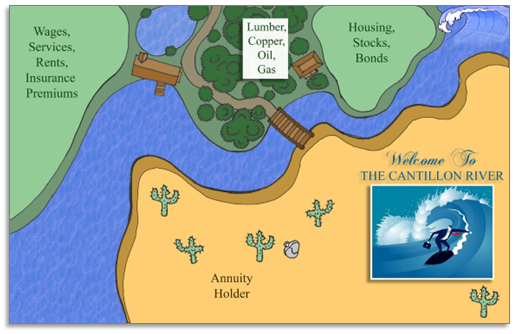

As a reminder, Richard Cantillon, in the early 1700s, expanded, in important ways, upon the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM). QTM, articulated by our firm eponym – Kopernik (Copernicus) back in 1517, and later made famous by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz in the 1960s, states that the general price level of goods and services is directly proportional to the amount of money in circulation. At Kopernik, we feel that “assets” ought to be added to “goods and services” in the equation. Cantillon argued that money is not neutral, that changes in money supply favor some at the expense of others, and some things sooner than others. It is his quote, “the river, which runs and winds about in its bed, will not flow with double the speed when the amount of water is doubled,” that brought Proud Mary to mind while observing the Fed’s latest misadventures.

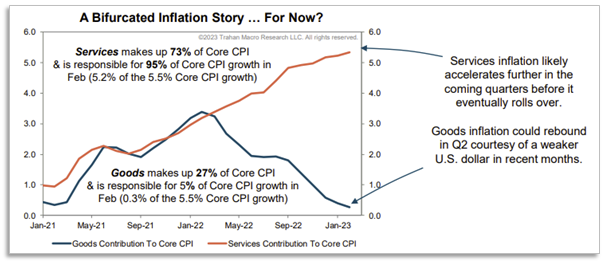

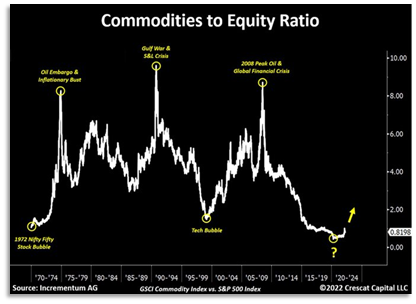

Proud Mary, of course, is a river boat. As we’ve all witnessed multiple times historically, things bob and weave unevenly on the “Cantillon river.” We’ve mentioned repeatedly, but it’s worth repeating, history shows that increases in money supply migrate first and foremost into financial assets, driving their prices upward. This is because central banks often increase supply by lowering interest rates that are an important ingredient in their valuation. More recently, central banks have directly given the newly printed currency to banks, big asset managers like BlackRock, and indirectly to large companies in need of cheap financing. Financial assets (stocks, bonds, similar interest-rate sensitive securities) should be viewed, figuratively, as near the source of Cantillon River. Higher prices for houses create demand for new homes which creates demand for lumber, carpenters, wages, insurance, services, brokers, etc. One by one, prices rise. The chart below illustrates that, three years into QE-infinity’s $4 trillion torrent, the inflation has worked its way pretty far downriver.

This chart from Trahan Macro Research hints at some important points. First, rising services prices tend to be problematic for central bankers. Many are suggesting that they are caught between a rock and a hard place. Secondly, though goods prices have had a serious price correction, notice that the blue line (representing change in price, not actual price) hasn’t gone below zero. Prices are still rising, though at a slower rate. Prices tend to settle at higher highs and higher lows during the cycles of increasing money supply. Trahan’s projection that goods prices turn higher again is likely not far off the mark, especially given the return to printing. As the prices of goods likely bounce around violently, but with an upward trajectory, there are important investment implications.

Investment Implications

Many people associate Proud Mary, not with CCR, but with Ike and Tina Turner. They covered the song several years later, reaching #4 on the charts. At the start of her iconic version, she promises audiences that at first, she and then-husband, Ike Turner, will take things “nice and easy,” but promises the ending will be “rough.” She delivers! Relative to CCR’s, her version is a better analogue for our narrative, perhaps more emblematic of the effects of QE (quantitative easing) on the markets. Early on, financial markets respond slowly to bouts of monetary easing, unsure that it can offset the severe ills that afflict the markets. Markets rise and over time investors gain confidence in central banks. Over a longer span of time, investors become increasingly confident that they can trust the central banks to come to the “rescue” whenever markets experience a hiccup. Eventually, investors behave like Pavlov’s dog, salivating every time the “QE” bell rings. A whisper that the bell may ring elicits drools. At manic peaks, behavior becomes more akin to rabid dogs. For examples of what this means for financial markets, please look up historical prices leading up to the stock market peaks of 1929, 1966, 1999, 2021, Japan in 1989, and gold in 1979. There is sufficient evidence that Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises was on the right track when he said that central banks, once they embark on a money printing track, can’t stop. Amounts increase over time, benefits wane; they migrate to goods and services “further downriver.”

Likewise, volatility starts out “nice and easy,” suppressed by the authorities. Near the peak, and during the subsequent correction, things get “rough” as bankers lose their battle to keep things tidy. Volatility becomes the order of the day. Kopernik’s prophecies were premature, but the world seems to have finally arrived at a place that punishes investors who employ models (such as Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)) using precise inputs pertaining to the distinctly unprecise future and is begging to reward investors who take advantage of optionality. Many option-laden assets undervalue the higher level of contemporary volatility. When it comes to many hard assets, we believe that investors have a generational opportunity to capitalize on mispricing resulting from market participants inappropriately using DCF models. This, in combination with the extremely cheap valuation levels, underinvestment in the area, and over-capitalization of financials mean that volatility could be quite large on the upside.

As bottom-up, fundamentals-based, active managers, we are happy when we see things differently from the crowds. It is why we chose Kopernik (who espoused the, at-the-time, highly unpopular heliocentric model of the universe) for our firm eponym. The market’s approach to valuing hard assets is, in our opinion, quite misguided and portends great opportunity for others. This cavernous difference in approach merits a quick discourse.

Most everyone understands that currencies lose value over time and therefore require a discounting mechanism. Dollars lose value versus things. By anchoring the price of things to a dollar price and then discounting that price over time, many models now show that stuff loses value over time. This is generally completely wrong. Currency’s loss of value over time is the same thing as the price of stuff going up in dollar terms, NOT down. For example, assuming that the price of gold or copper drops (discounted) every year means that each year into the future trends the value of mineral reserves towards zero. This is a colossal mistake.

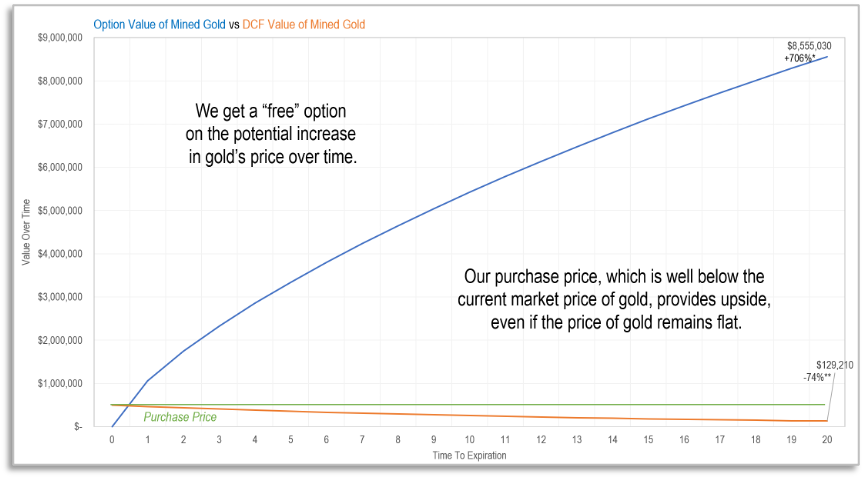

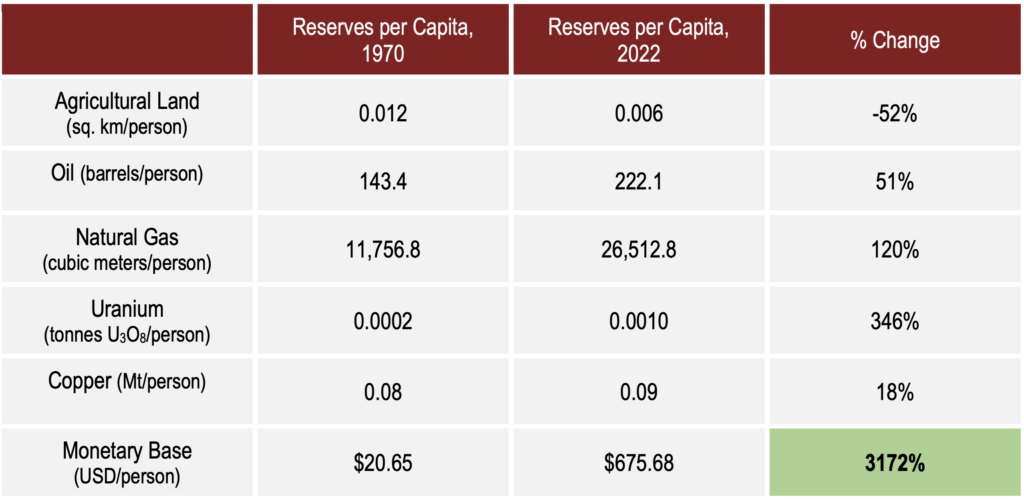

When something is scarce, hard to find, and necessary, its value is highly likely to increase with time. Large, long-lived reserves are the most valuable, not the least valuable. The following chart illustrates the magnitude of the potential mispricing.

**Assumes gold depreciates with the dollar | Assumes a discount rate of 7% per year

Assumes Gold price of $1,750 | Assumes strike price of $1,800 | Assumes interest rate of 3% | Assumes volatility of 15%

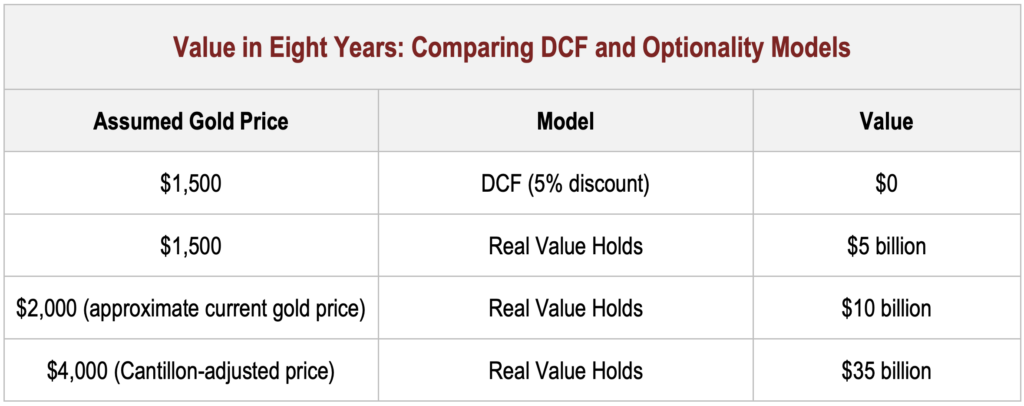

In this example, a DCF model indicates that a given resource will lose three-quarters of its value over two decades. It also highlights that a 20-year option to benefit from possible price increases is worth eight times more than a similar one-year option. It makes a big difference which models one uses. At the risk of saturation, a quick, specific example may be useful. A company we believe is misvalued is Seabridge Gold, Inc. (SEA CN, SA US). They own the valuable KSM project in British Columbia, Canada. The project has almost 90 million ounces of gold. To keep the numbers easy, we’ll approximate: we cut the number in half, since much of it won’t get recovered during processing – leaving 45 million oz. We then haircut the Measured & Indicated portion of the resource base by a third, trimming another 5 million ounces. Of the 40mm remaining, we assume that half will have to be given up in exchange for gaining a partner to build the mine. We now have 20mm ounces left. Furthermore, we subtract a heavy margin of safety to account for factors such as: difficulty of building and operating a mine, the share dilution that usually happens at mining companies (including this one), the time required to realize revenues, and changing geopolitics. We’ve conservatively whittled 90mm ounces down to 10mm before commencing valuation models. What are these ounces worth?

Conservatively assuming total costs per ounce of $1,000 and an ultra-conservative industry expectation for the gold price of $1,500 leaves a profit of $500/oz. 10 million ounces are worth $5 billion dollars. This is five times the current market capitalization. Worth the wait. But, if one were to utilize a DCF model and assume that the price of gold declines by 5% annually (as opposed to rising 5% as the dollar declines), half of this value is gone in a little over three years. It is worthless in eight years, as the assumed price of gold falls below the cost of extracting it!

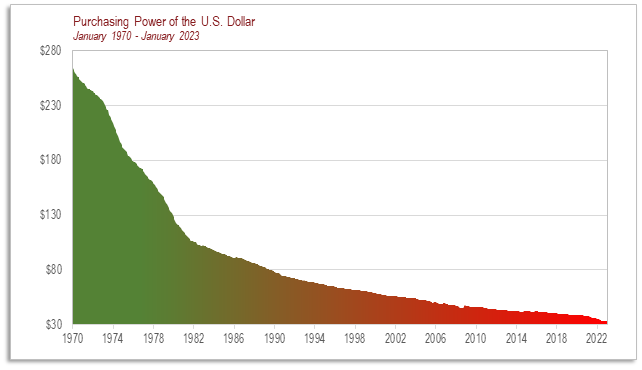

This is not to suggest that any of these scenarios happen, only to show different outcomes from differing assumptions. We like situations where stocks are undervalued when modeled at current prices and optionality is then effectively “free:” real prices move higher; inflation moves prices higher; more ounces are found (as commonly happens during mining); and the other properties and metals that Seabridge has are valuable (we conservatively assigned no value in our analysis above). The chart below illustrates that an assumption that the dollar will lose significant value versus real assets has been a winning proposition for the last half-century.

Investment Strategy

Current fundamentals suggest that the investment environment is favorable: eight billion people, a deluge of trillions of dollars of currency, quasi-fixed quantities of food, shelter, useful sources of power and heat, metals for cell phones, EVs, windmills, and many of the things on which society has become dependent.

Agency, International Atomic Energy Agency, Canadian Minerals Yearbook 1970

Each person can form their own opinion as to whether useful hard assets are likely to rise or fall in price relative to dollars/yen/yuan/euros/pounds/etc. We have our opinion, but as bottom-up investors, we relish the fact that inflation beneficiaries are priced so attractively that they should perform well sans inflation. Investors gain a “free” valuable call option on the possibility of inflation.

If the authoritarian COVID shutdowns, and resultant supply chain issues, have taught society anything, it is that the reason money is valuable is that it affords us the ability to purchase those things that really matter. It turns out that people stood ready to exchange a great many euros, dollars, yen, to gain access to food, heat and shelter. Cell phones, computers, transportation, and the energy that powers them, are high on the list as well.

Despite naming this missive after a riverboat, we confess that as “Proud Mary’s” stock prices bobbed upward on the volatile “River Cantillon” we’ve recently sold our remaining shipping stocks. We still happily hold stocks of trains, planes, and automobiles, and look forward to a chance to reinvest in shipping at a lower price. We still are finding tremendous value in other infrastructure franchises such as cell phone providers and electricity producers (especially low cost, low CO2 hydro and nuclear based).

As per the case laid out above, commodities are cheap, option-laden, and are likely beneficiaries of years of underinvestment in conjunction with wanton monetary and fiscal policy. Long-lived reserves are paradoxically the most desirable and the least valued in the marketplace. We continue to be significantly invested in uranium, natural gas, industrial metals, and especially precious metals.

In 2020, Haute Living asked Ms. Turner to play a word association game. Prompted with “Proud Mary” her response was “Freedom.” Perhaps stores of value, such as hard assets – for which we’ve been using the riverboat Proud Mary as analogue – represent freedom for investors suffering under central bank induced “financial repression.”

Concluding Thoughts

Proud Mary, like a lot of CCR songs, made it to #2 on the hit charts. Despite all their success, they never had a number one song. Interestingly enough, Fogerty had a number one hit years later with “Centerfield.” The song draws heavily on the famous poem, “Casey’s at Bat,” written in 1888 by Ernest Thayer. The poem is about the fictional “Mudville” baseball team and the arrogant star – Casey, whose over-confidence contributes to a loss. In Centerfield, Mr. Fogerty laments,

“Well, I spent some time in the Mudville Nine, Watching it from the bench, You know I took some lumps.”

Commentators point out that the song is somewhat biographical, as Fogerty had taken a couple year hiatus from the music industry during legal disputes with his former record label. He undoubtedly felt like he was “riding the pine” and yet was “ready to play, today.”

At any rate, as the “Proud Mary” and other vessels, and a whole host of other assets figuratively bob and weave down the “Cantillon River,” a plethora of challenges and opportunities are being created for asset managers and stewards of funds. We, perhaps wishfully, point out that the “Caseys” of the past decade of zero interest rate policy, may not be the ones to count on to perform over the coming decade. Perhaps Fogerty speaks for all value managers when he croons,

“Oh, put me in coach, I’m ready to play today

Put me in coach, I’m ready to play today

Look at me, I can be centerfield”

Slugging averages appear poised to soar for managers focused on valuations, fundamentals, real assets, and emerging markets.

As March Madness winds down, and the baseball season gets underway in earnest, here’s to your favorite team and more importantly, to a healthy, happy, prosperous 2023.

Cheers,

David B. Iben, CFA

Chief Investment Officer

March 2023

“And I never lost one minute of sleepin’

Worryin’ ’bout the way things might have been

But I never saw the good side of a city

‘Til I hitched a ride on a riverboat queen”

-John Fogerty, Proud Mary,

perhaps giving advice on hard asset investing 😉

Important Information and Disclosures

The information presented herein is confidential and proprietary to Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is not to be reproduced in whole or in part or used for any purpose except as authorized by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any product or service to which this information may relate.

This letter may contain forward-looking statements. Use of words such was “believe”, “intend”, “expect”, anticipate”, “project”, “estimate”, “predict”, “is confident”, “has confidence” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current observations, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, estimates, and projections. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors, some of which are beyond our control and are difficult to predict. As a result, actual results could differ materially from those expressed, implied or forecasted in the forward-looking statements.

Please consider all risks carefully before investing. Investments in a Kopernik strategy are subject to certain risks such as market, investment style, interest rate, deflation, and illiquidity risk. Investments in small and mid-capitalization companies also involve greater risk and portfolio price volatility than investments in larger capitalization stocks. Investing in non-U.S. markets, including emerging and frontier markets, involves certain additional risks, including potential currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, less liquidity, less disclosure, and the potential for market volatility, expropriation, confiscatory taxation, and social, economic and political instability. Investments in energy and natural resources companies are especially affected by developments in the commodities markets, the supply of and demand for specific resources, raw materials, products and services, the price of oil and gas, exploration and production spending, government regulation, economic conditions, international political developments, energy conservation efforts and the success of exploration projects.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. There can be no assurance that a fund will achieve its stated objectives. Equity funds are subject generally to market, market sector, market liquidity, issuer, and investment style risks, among other factors, to varying degrees, all of which are more fully described in the fund’s prospectus. Investments in foreign securities may underperform and may be more volatile than comparable U.S. securities because of the risks involving foreign economies and markets, foreign political systems, foreign regulatory standards, foreign currencies and taxes. Investments in foreign and emerging markets present additional risks, such as increased volatility and lower trading volume.

The holdings discussed in this piece should not be considered recommendations to purchase or sell a particular security. It should not be assumed that securities bought or sold in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of the securities in this portfolio. Current and future portfolio holdings are subject to risk.