A Differentiated Approach to ESG (July 2022)

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing has been around for many decades, yet over the past few years, growth in ESG investing has turned hyperbolic. Yet how to define ESG is difficult. Despite the efforts of many, there is no consistent framework or set of ESG standards – and nor should there be, in our view. At the basis of this paper is a simple argument: ESG is important, complex, and nuanced. It is too important, complex, and nuanced to outsource to rating agencies or other entities that do not have a fiduciary duty to our clients. Just as the financial industry has tried to boil risk down into one single component (volatility), ESG consultants and rating agencies, which have grown in number as assets in ESG funds have grown, have similarly tried to simplify a subjective risk into a simple number and categorize industries and companies in black and white terms. According to many in the ESG world, an industry or a company is either a “good” ESG company or a “bad” ESG company (and usually this designation seems to go hand in hand with one metric – CO2 emissions).

We do not believe that any company is fundamentally good or bad; they are both. Most companies both contribute positively and impact negatively. Our job, as allocators of capital, is to understand the risk we are taking so that we can make sure we are being appropriately compensated for it, and, hopefully, reduce our risk by engaging with companies. It is our belief that sound ESG practices are important in maintaining and growing the intrinsic value of the underlying business. It seems intuitive that companies that act ethically and balance the interests of all corporate stakeholders – including the environment, employees, customers, suppliers, community members, the government, and shareholders – are more likely to attract and retain top-notch employees, loyal and satisfied customers, and welcoming communities while being less likely to encounter opposition and appropriations.

Complementing our March 2021 webinar, our goal with this whitepaper is to give an update on how we think about the current ESG environment, provide examples of the types of ESG risks we are evaluating in each sector, and explain how we integrate ESG risk into our valuation process.

The Current ESG Landscape

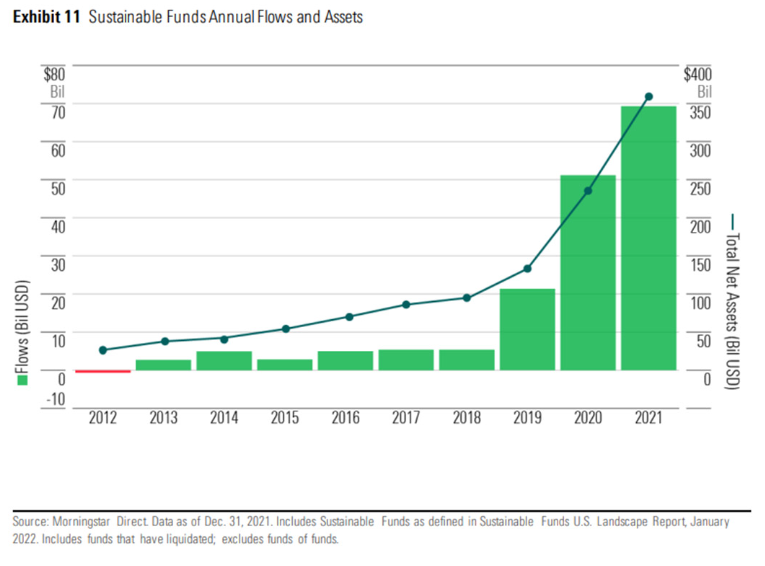

Although ESG investing is not new, it has grown in popularity over the last few years (see chart of assets under management below).

2021 was a record year for ESG flows—according to Morningstar, sustainable funds had $69.2 billion of net flows during the year.1 Within these flows, passive ESG investing continues to gain market share, particularly in the U.S., where passive strategies have attracted, on average, two-thirds of quarterly sustainable fund flows over the last three years.2

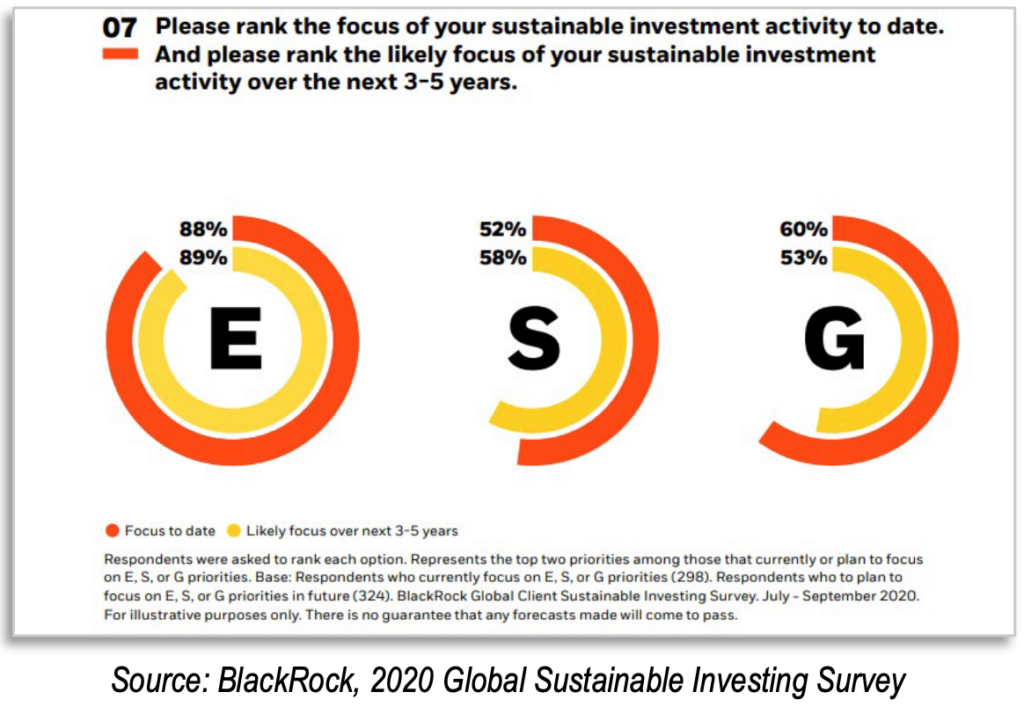

Unsurprisingly, the number of both ESG funds and research support entities has increased alongside asset growth: according to Morningstar, there were 6,452 sustainable funds at the end of Q1 2022, and as of 2022 there are more than 140 different providers of ESG of data, research, and rankings.3 As climate change dominates the minds of many investors interested in ESG, funds and ratings agencies seem to be focused predominantly on the first letter of the ESG acronym, E.

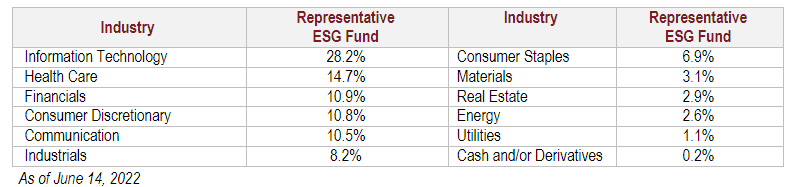

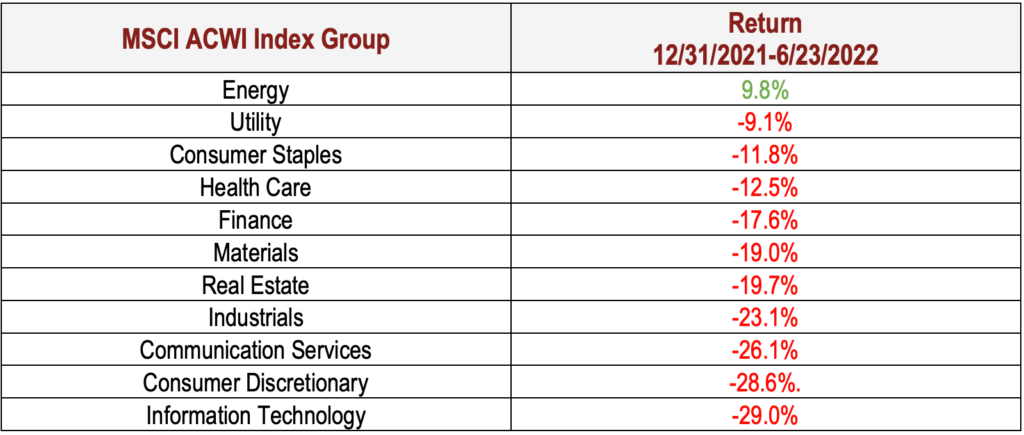

With this focus on environmental factors, many asset-light sectors such as technology, consumer discretionary, financials, and health care tend to get higher ESG scores while the energy, utilities, and materials sectors receive lower scores. Since many ESG funds screen out companies with low scores, it is not surprising that many ESG funds are overweight these asset-light sectors and underweight the resource intensive sectors.

Critical rhetoric is absent when performance is good but has a way of showing up when performance is challenged. As technology and health care outperformed for many years, ESG funds sparkled. The shine is wearing off for the first time this year as investors have seen that one of the most underweight sectors, energy, is the only sector that has had positive performance this year to date. Worse, the most overweight sector, technology, has been the worst performing sector. In addition, recent negative news headlines of ESG funds’ actions not living up to their marketing materials have further spoiled the ESG party.

This change in attitude does not make evaluating ESG risk any less important for Kopernik. We have long believed that the way the industry integrates ESG risks is flawed; first and foremost, the over reliance on ratings agencies leads to an oversimplification of the risk. Many ESG funds simply buy the highest rated ESG companies as determined by Sustainalytics or MSCI ESG (the two biggest rating agencies) and shun the lowest rated companies. How those ratings are determined then becomes very important.

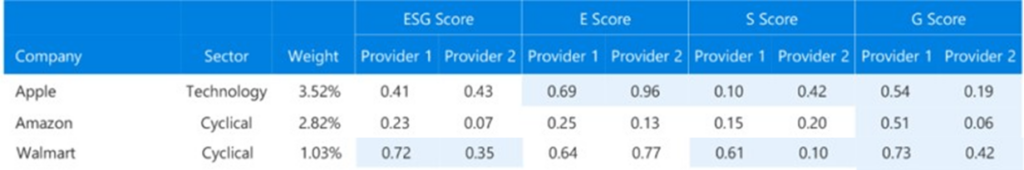

We find two significant issues. First, as discussed earlier, ESG risk is very subjective and much harder to quantify than, for example, credit risk; the correlation between rating agencies is very low. As the below table shows, agencies’ ratings vary wildly. For example, one agency rates Walmart a 35 while another gives it a 72 – which rating agency is utilized could make a significant difference in the portfolio weighting.

Source: Research Affiliates, January 2020

Secondly, materiality matters, and ESG ratings can give high scores even when there is a serious risk. In 2020, the Financial Times wrote a very interesting piece about a company named Solvay, a chemicals company with a plant in Rosignano, Italy. The area is often referred to as the “Italian Maldives,” and tourists flock to the water, which has a beautiful chalky blue color. The company received a very high ESG score from one of the top rating agencies because it performed well in many areas, including greenhouse gas emissions. However, this high score masks the true ESG risk: unfortunately for those swimming, the chalky blue water is a result of untreated chemical discharges from a nearby Solvay plant, some of which are toxic. The company, despite agreements with Italian institutions to do so, has never been able to reduce their discharges and has since said the task would be impossible. So far, the government has been willing to look the other way. From an investor’s perspective, one of the main financial risks is that the government stops allowing them to dump waste into the ocean. This is not reflected in the high ESG rating; thus, equally weighting many different ESG metrics dilutes materiality.4

We prefer to rely on our independent analysis, integrating ESG risk into our company-specific risk adjustment process. We will devote the rest of this whitepaper to highlighting some of the ESG risks we see in sectors and attempt to point out the inefficiencies in the marketplace as investors rush to categorize ESG risk in black or white terms.

Technology

Material ESG issues: Social (data security and privacy, user welfare); Governance (corporate pay structure, share classes)

There is a lot to be excited about in the technology sector. Social media has made it easier to be an entrepreneur or find a significant other; internet browsers have made information much quicker and easier to access; map and shopping apps make our daily lives more convenient; and technology is revolutionizing healthcare as artificial intelligence can, with the help of a doctor, diagnose diseases faster and more accurately. The positives are easy to see, and the FAANG stocks have been favorites of many ESG funds as they are resource light businesses and do not emit much CO2.

However, as the share prices have fallen, the societal costs to new technologies are now comprising more of the rhetoric. In our webinar last year, we highlighted that all that glitters is not gold. Data security and privacy are key issues. The Cambridge Analytica story from the 2016 U.S. presidential election is just one prominent example; according to the Pew Trust, 13% of Americans have had their social media accounts taken over by an unauthorized user.5

Additionally, consumer welfare is a concern. Teen suicide rates have skyrocketed with the rise of social media. A 2021 study in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence found that “girls who used social media for at least two to three hours per day at the beginning of the study—when they were about 13 years old—and then greatly increased their use over time were at a higher clinical risk for suicide as emerging adults.6 Worse, it appears that Facebook executives have been well aware of these issues for a long time.7

There are other social difficulties as well. It is hard to know what information is real or fake. One study found that on Twitter, fake news travels six times faster than true stories.8 It is not just that the news itself is incorrect, although that is certainly a problem. More importantly, that information shapes peoples’ behaviors. The 2020 Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma offered a detailed look at how dangerous it can truly be online.

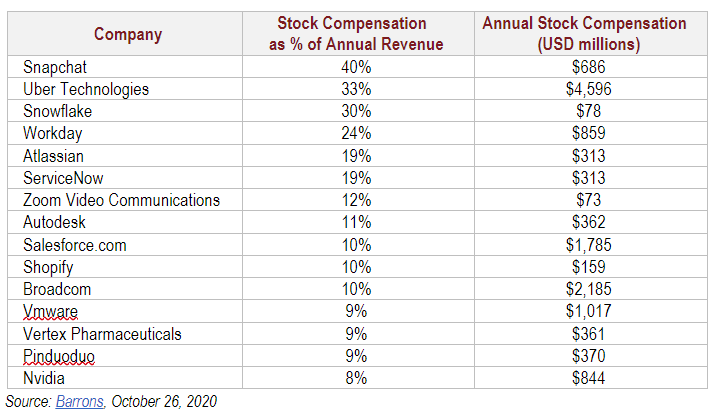

In addition to the social issues, corporate governance is also problematic in technology. The table below shows how technology companies in general pay a large percentage of their revenue to insiders:

Additionally, the percentage of IPOs with dual class shares continues to rise, and many technology companies have their chairman and CEO as the same person.9 It seems clear to us that, even with the recent selloff in the technology sector, social media and technology companies still do not price in these social and governance risks.

Lastly, it is also worth pointing out that, while tech companies tend to have a relatively low environmental impact, they require other companies to mine metals, process silicon, and generate electricity.

Consumer Staple and Discretionary Products

Material issues: Social (human capital/labor practices, product quality and safety); Governance (supply chain management, materials sourcing); Environmental (ecological impacts, use of plastics)

Consumer staples and discretionary products add convenience to our lives. People all over the world have access to relatively fresh food, and many things that were extreme luxuries historically are now part of daily life. Yet there is also a cost. Cheap clothing requires cheap labor, which frequently exploits workers, particularly children. Reports have found that children work in the assembly of garments, taking on tasks such as sewing on buttons, cutting threads, and moving and packing garments.10 The bottled water industry is a blessing in some areas, as roughly 1.2 billion people in the world lack clean drinking water, yet the mass production of bottled water impacts local water supplies.11

Another key issue: packaging and plastics, particularly single-use plastics, which are meant to be used once and then thrown away or recycled. Starbucks, for example, uses more than 8,000 cups per minute, or 4 billion per year.12

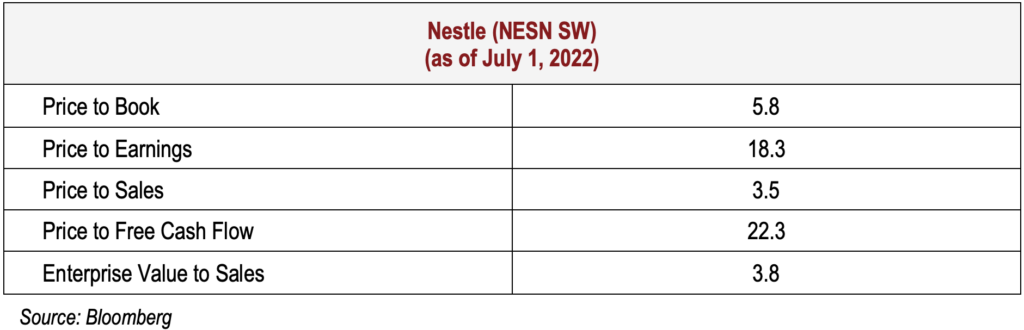

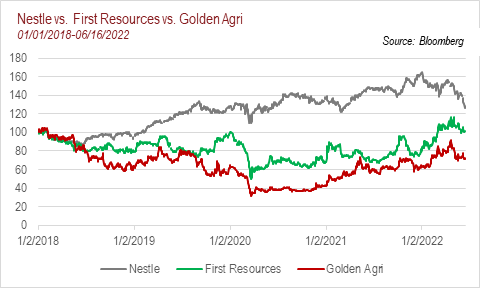

Environmentalists decry the use of single-use plastics and consider them a key form of pollution that must be dealt with; the market seems not to care. Major plastics producer Nestle, for example, seems to not price in any environmental risk, as shown below:

Another inefficiency in the marketplace that we see is the difference between the producers of palm oil and the largest users of it. Nestle is one of the world’s largest users of palm oil yet is rated very highly by ESG companies, meanwhile, the producers of palm oil have long been rated poorly by ESG community. The palm oil companies have a bad reputation, and deservedly so for their actions in the past. The companies historically deforested huge amounts of land and treated the local communities very poorly, effectively pushing them off their land.

However, as investors, we are forward looking, and when we engage with the palm oil companies that we own, it has become clear to us that they have made great strides along the ESG front. For example, Golden Agri-Resources Ltd (“Golden Agri”), a large palm oil company, did not have a sustainability department 10 years ago, and now they have almost 350 people working in this department. All the major players in the industry have signed on to a “No deforestation, no peat, and no exploitation policy.”13

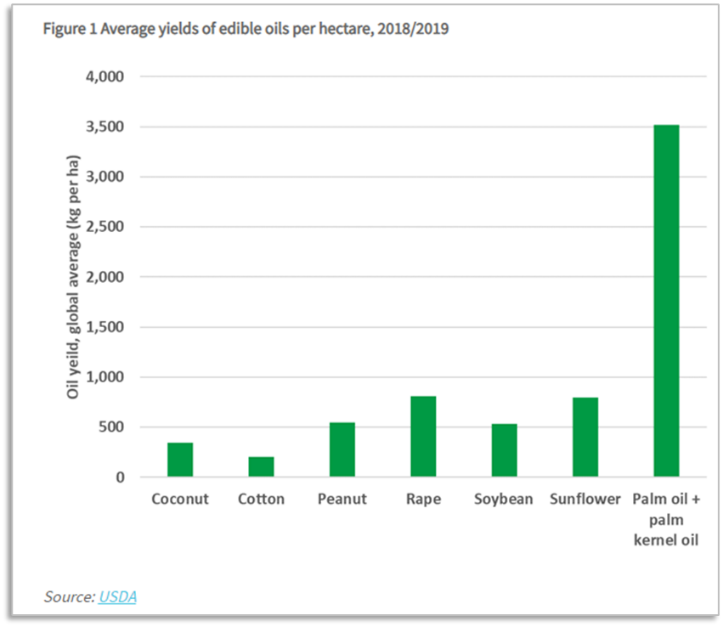

Further, we should point out that while deforestation can be a problem for any agriculture company, palm oil is one of the most land efficient plant oils. It has 7 times the yield of soybeans!

Photos of palm oil plantations taken by Kopernik analyst Taylor McKenna

Thus, we find it curious that one of the largest consumers of palm oil is not penalized the same way that a palm oil producer is, even though the latter has been making significant strides to reduce its ESG risk while the former’s plastic pollution issues seem to be extremely difficult to address. Admittedly, since our webinar in March of 2021, the market is starting to rectify this mispricing.

Financials

Material issues: Social (consumer welfare, selling practices); Governance (business ethics, competitive behavior)

Banks play an important role in society. As an intermediary between spender and saver, banks allow for people to finance homes, take loans out for businesses, and buy things that make people more productive and life more enjoyable.

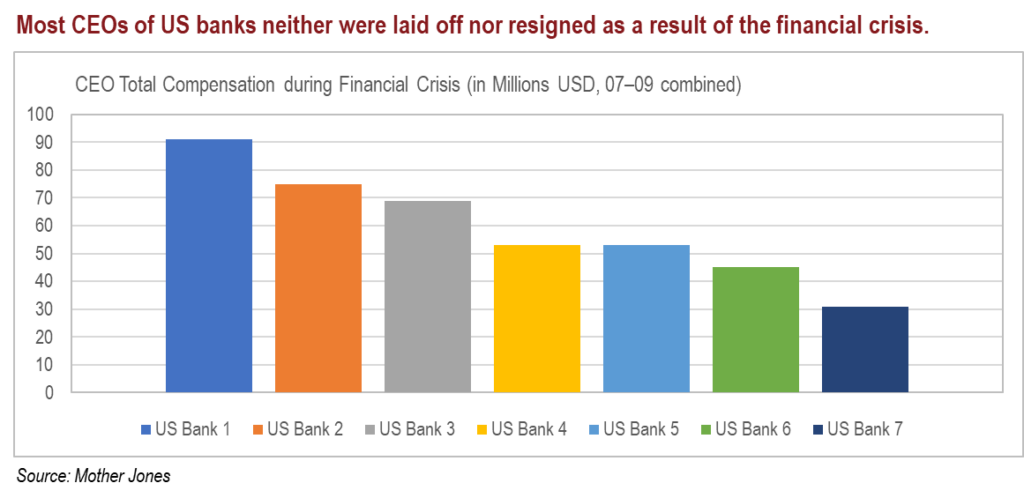

Yet history has proven that banks can have large social costs and governance risks. If one sees a headline about a bank being a bad actor, no one is too surprised. Global banks are regularly paying large fines for infractions: financial regulators levied $10.4 billion in fines in 2020.14 What was the societal cost, the cost to taxpayers, when the Federal Reserve had to bail the banks out for making extremely irresponsible loans leading up to the financial crisis? And what lessons did the bank CEOs learn from that? If one watches the 2010 documentary Inside Job, or any other film about the global financial crisis, the answer is clear: they didn’t learn any.

Health Care

Material issues: Social (product quality & safety, access & affordability, selling practices); Governance (competitive behavior, business ethics)

There is no doubt that health care is a very important industry. With improvements in drug development, diseases that used to be death sentences are now things that can be treated, and people can live normal lives. Breast cancer and hemophilia are good examples, as advances in screening and therapies have led to better treatment of breast cancer, and hemophilia treatments have extended life expectancy close to 6 decades.15

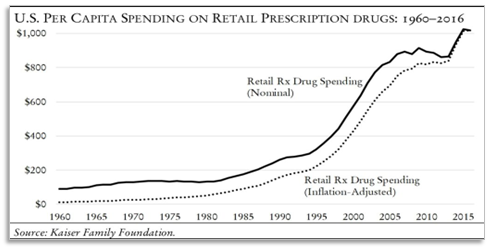

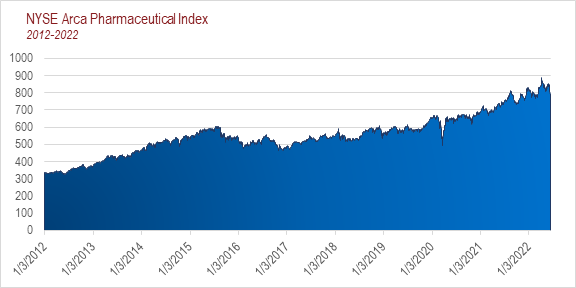

However, it does society no good to have all these treatments if no one can access them. Healthcare costs in the United States are out of control, as Elisabeth Rosenthal explains in her 2016 book An American Sickness: How Healthcare Became Big Business and How You Can Take It Back. Prescription drug costs in the U.S. are one of the major issues. Costs are so high that many people do not fill prescriptions or skip doses because they are unable to afford their medication. Drug spending has outpaced inflation for many decades, as shown in the chart below:

There are clear sustainability risks in the health care industry. For example, if drug prices in the U.S. fell to the same level as prices elsewhere in the world, the sales and profits of drug companies would drop significantly. We believe there is a possibility that prices will be regulated in the future; however, the market is clearly not pricing in any move to bring U.S. prices in line with the rest of the world. It also is not valuing the possibility that technology, such as wearables and other forms of preventative medicine, may significantly lower the need for over-priced drugs in the future.

Energy

Material issues: Environmental (greenhouse gas emissions, air quality, ecological impacts)

Energy as a sector usually gets low ESG scores or is left out of ESG funds entirely due to its clear environmental impact. The environmental cost of hydrocarbons is high. C02 levels are rising and most people in the world breathe polluted air, which kills 7 million people a year.16 However, energy touches almost every part of our lives, and fossil fuels make up the majority of the world’s energy usage. It is hard to imagine living life without lights, or without air conditioning or heating. The recent rise in energy prices, and the knock-on effects, demonstrate how inelastic energy demand is.

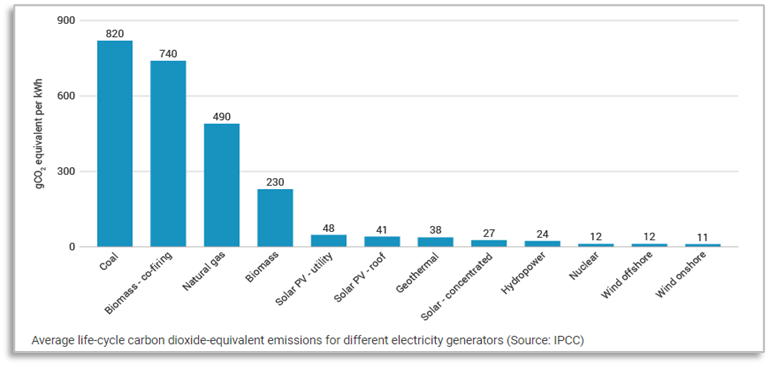

If the world is going to continue to develop economically, the world will need more power. Coal is clearly the dirtiest form of energy, and many would hope to replace coal with cleaner natural gas or renewable forms of energy, such as wind or solar power. Yet many don’t consider the carbon footprint of “renewable” power. To be clear, there is nothing renewable about solar and wind. The solar panels and windmills have a lifespan just like all machinery and need to be replaced, which will require more materials to be mined since recycling is impossible, currently. Further, these technologies require an enormous amount of land. A natural gas fired power plant the size of a residential home can produce enough power to power 75,000 homes. An equivalent amount of wind power would require 20 windmills and 10 square miles of land!17

Nuclear power seems to us to be a very viable option for clean power. It is clean, cheap, and provides base load power; however, there is reputational risk, and nuclear waste must be safely stored. Likewise, hydroelectricity, while clean, can have ecological impacts, such as diverting rivers or changing fish habitats.

The takeaway is that energy is a necessary part of our daily lives. Divesting of oil or fossil fuel companies does nothing to change the demand. We support the transition away from coal and away from fossil fuels; however, we recognize that this transition will likely take decades to happen. And we recognize that fossil fuels like natural gas are an important part of the energy transition. The ESG push to divest from all fossil fuels, which was most strongly felt in late 2020 and early 2021, was an opportunity, and one that Kopernik took advantage of: 25% of our portfolio was invested in energy companies in 2020 and 2021. With the runup in prices, we have realized gains and taken the Global All-Cap strategy’s energy sector position down to 15%.

Industrials

Material issues: Environmental (energy management, ecological impacts, greenhouse gas emissions); Governance

Industrials are another underrepresented industry in ESG indexes, unsurprisingly because many are asset-heavy manufacturing businesses with a significant environmental impact. However, machines make the world go round. Shipping, air travel, trucks, water purifiers, railroads, E&C companies for infrastructure – we all benefit daily because these products are being made.

Yet, just like all the other industries, there are pros and cons. There are clearly environmental costs but also governance issues in this space. Bribes for contracts are not uncommon – probably more common than not in many parts of the world. And while corporate governance is a risk for all companies, some industrial companies rival technology companies for egregiously poor governance.

Materials

Material issues: Environmental (ecological impacts, water and wastewater management); Social (community relations)

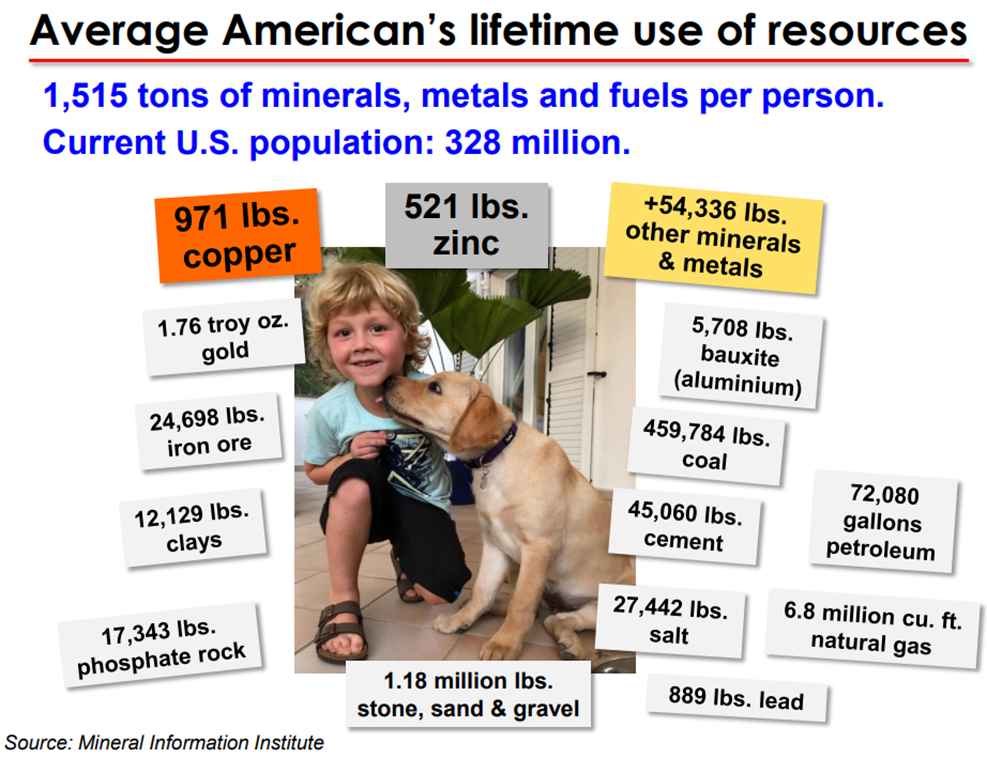

The Materials sector is ranked the lowest of all sectors in most ESG indexes, unsurprisingly because it is a very resource intensive business; mining companies have a history of poor governance; and they are exposed to social unrest and protests. As a result, they are very under-owned in ESG funds. However, mining companies are a very important part of a modern economy. It is very difficult to get away from the products produced by mining companies, as the graphic below shows. There are no houses, cars, computers, phones, windmills or solar panels without mining.

We find it interesting that ESG funds are shunning mining companies but support the tech names and alternative energy stocks that depend on these materials being mined. Plug-in electric vehicles require at least 5 times more copper than a traditional gasoline engine; electric vehicles will also require significantly more lithium, cobalt, nickel, and graphite. Building just a single 100-megawatt wind farm requires roughly 30,000 tons of iron ore, 50,000 tons of concrete, and 900 tons of plastics.18 Mining is required to make a transition to clean energy and a necessity for a functioning economy. Mining companies, therefore, are absolutely essential and will benefit if we are to make this transition to cleaner technologies.

The ESG risks are real. Often mining companies are moving tons of earth to extract pounds of the final product, which is very disruptive to the environment. Tailings dam breaks, when they happen, dump lots of waste into the rivers, killing fish and other aquatic life. Mining companies in the past used to treat the communities poorly and use up all the water, leaving nothing for the farmers.

Like palm oil companies, mining companies in the distant past were extremely bad actors, yet it has been one of the industries that has made some of the biggest changes in the field. As companies saw community unrest, violent protests, damage claims, and permits being pulled because of environmental accidents, they realized that following best ESG practices was good for business.

As a result of their efforts over recent decades, tailing dams disasters are less frequent, and mining deaths have dropped significantly. Mining companies are building schools and hospitals, helping communities develop economies, and sharing more of the economics with the communities. In many countries, they are taking on responsibilities that a local government might take on.

Integrating ESG Risk into Our Valuation Process

We have had an ESG policy at Kopernik since inception (as did our predecessor firm), and in 2018 we signed onto the UNPRI (UN Principles of Responsible Investment).

We have always preferred engagement to divestment. Minerals are going to be mined, barrels of oil are going to be produced, social media is going to be used, drugs are going to be prescribed and taken, plastic is going to be consumed, houses heated, and transportation utilized. Selling our shares to a buyer who does not share our ESG supportive long-term views does nothing to fix the problems the world faces. In our view, when the financial industry decides to divest for reasons not based on price, it is usually an opportunity to buy. As we saw with energy stocks in 2020 and 2021, the stock market was over discounting the negative ESG risk while not recognizing the positive contributions to society that energy provides. On the flip side, there are industries such as technology and health care where, in our opinion, the market is not discounting the ESG risk enough.

As allocators of capital, it is our job to understand the risks to our investments – geopolitical, ESG and financial – so that we can properly risk adjust our theoretical values. If a company has material ESG risks, we will then want a larger margin of safety before we invest. In terms of portfolio impact, larger margins of safety means that the upside may not be large enough to deploy capital or make it a large position.

In our opinion, engaging to affect change in less than perfect companies does more good than buying companies that have little room for improvement (and, arguably, every company has room for improvement in some area). And affecting this change has both social and financial benefits, as it arguably both improves the world and simultaneously increases the multiple of the stock.

In summary, it should be clear that ESG is complex. All industries are good, and they all have their challenges. Environmental, social, and governance issues require thought. They require rigorous analysis. We will continue to rely on our independent thought and take advantage of extreme times in the market.

As always, thank you for your support.

Kopernik Global Investors

Investment Research Team

July 2022

Important Information and Disclosures

The information presented herein is confidential and proprietary to Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is not to be reproduced in whole or in part or used for any purpose except as authorized by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any product or service to which this information may relate.

This letter may contain forward-looking statements. Use of words such was “believe”, “intend”, “expect”, anticipate”, “project”, “estimate”, “predict”, “is confident”, “has confidence” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current observations, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, estimates, and projections. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors, some of which are beyond our control and are difficult to predict. As a result, actual results could differ materially from those expressed, implied or forecasted in the forward-looking statements.

Please consider all risks carefully before investing. Investments in a Kopernik Fund are subject to certain risks such as market, investment style, interest rate, deflation, and liquidity risk. Investments in small and mid-capitalization companies also involve greater risk and portfolio price volatility than investments in larger capitalization stocks. Investing in non-U.S. markets, including emerging and frontier markets, involves certain additional risks, including potential currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, less liquidity, less disclosure, and the potential for market volatility, expropriation, confiscatory taxation, and social, economic and political instability. Investments in energy and natural resources companies are especially affected by developments in the commodities markets, the supply of and demand for specific resources, raw materials, products and services, the price of oil and gas, exploration and production spending, government regulation, economic conditions, international political developments, energy conservation efforts and the success of exploration projects.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. There can be no assurance that a fund will achieve its stated objectives. Equity funds are subject generally to market, market sector, market liquidity, issuer, and investment style risks, among other factors, to varying degrees, all of which are more fully described in the fund’s prospectus. Investments in foreign securities may underperform and may be more volatile than comparable U.S. securities because of the risks involving foreign economies and markets, foreign political systems, foreign regulatory standards, foreign currencies and taxes. Investments in foreign and emerging markets present additional risks, such as increased volatility and lower trading volume.

The holdings discussed in this piece should not be considered recommendations to purchase or sell a particular security. It should not be assumed that securities bought or sold in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of the securities in this portfolio. Current and future portfolio holdings are subject to risk.

- Will Schmitt, “ESG funds enjoy (another) record-breaking year, winning $69bn of new money,” CityWire, February 9, 2022 ↩︎

- Morningstar, “Global Sustainable Fund Flows: Q1 2022 in Review,” accessed June 15, 2022. ↩︎

- “8 Best ESG Rating Agencies – Who Gets to Grade?” accessed 15 June 2022. ↩︎

- Financial Times, The factory by a Tuscan beach and the future of ESG investing, December 22, 2020. ↩︎

- Key Social Media Privacy Issues for 2020, Tulane University School of Professional Advancement. ↩︎

- “10-year study shows elevated suicide risk from excel social media time for teen girls,” Brigham Young University ↩︎

- BBC, “Facebook under fire over secret teen research,” September 15, 2021. ↩︎

- “Study: On Twitter, false news travels faster than true stories,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ↩︎

- “Dual-Class Shares: Governance Risk and Company Performance,” ISS, June 13, 2019 ↩︎

- “Child labour in the fashion supply chain: Where, why and what can be done,” The Guardian, retrieved May 21, 2021. ↩︎

- “Here’s how Nestle is leaving millions in Pakistan, Nigeria, and Flint without clean water,” The Muslim Vibe, January 17, 2018. ↩︎

- Clean Water Action, “Starbucks and Our Plastic Problem,” accessed July 1, 2022. ↩︎

- NDPE Commitment, “No Deforestation, Peat, and Exploitation,” retrieved May 24, 2021. ↩︎

- Jaclyn Jaeger, “Fines against financial institutions hit $10.4 billion in 2020,” Compliance Week, December 22, 2020. ↩︎

- Hemophilia News Today, “Hemophilia Prognosis and Life Expectancy.” ↩︎

- World Health Organization, “Air Pollution,” retrieved May 26, 2021. ↩︎

- Chris Martin, “Wind Turbine Blades Can’t Be Recycled, So They’re Piling Up in Landfills,” Bloomberg Green, February 5, 2020; David Biello, “Electric Cars are Not Necessarily Clean: Your battery-powered vehicle is only as green as your electricity supplier.” Scientific American, May 11, 2016; Samantha Gross, “Renewables, Land Use, and Local Opposition in the United States.” Brookings Institute, January 2020. ↩︎

- Mark P. Mills, “Mines, Minerals, and ‘Green’ Energy: A Reality Check,” the Manhattan Institute, July 9, 2020. ↩︎