Q3 2025 Conference Call

Edited Transcript of the 3rd Quarter 2025 Conference Call with Dave Iben and Alissa Corcoran

Kopernik reviews the audio recording of the quarterly calls before posting the transcript of the call to the Kopernik website. Kopernik, in its sole discretion, may revise or eliminate questions and answers if the audio of the call is unclear or inaccurate.

October 30, 2025

4:15 pm ET

Mary Bracy: Good afternoon, everyone. I’m Mary Bracy, Kopernik’s Managing Editor of Investment Communications. We’re pleased to have you join us for our third quarter 2025 investor conference call. As a reminder, today’s call is being recorded. At any point during the presentation, if you have a question, please type it into the Q&A box. We’ll be happy to answer it as part of our Q&A session at the end of the call. Now I will turn the call over to Mr. Kassim Gaffar, who will provide a quick firm update.

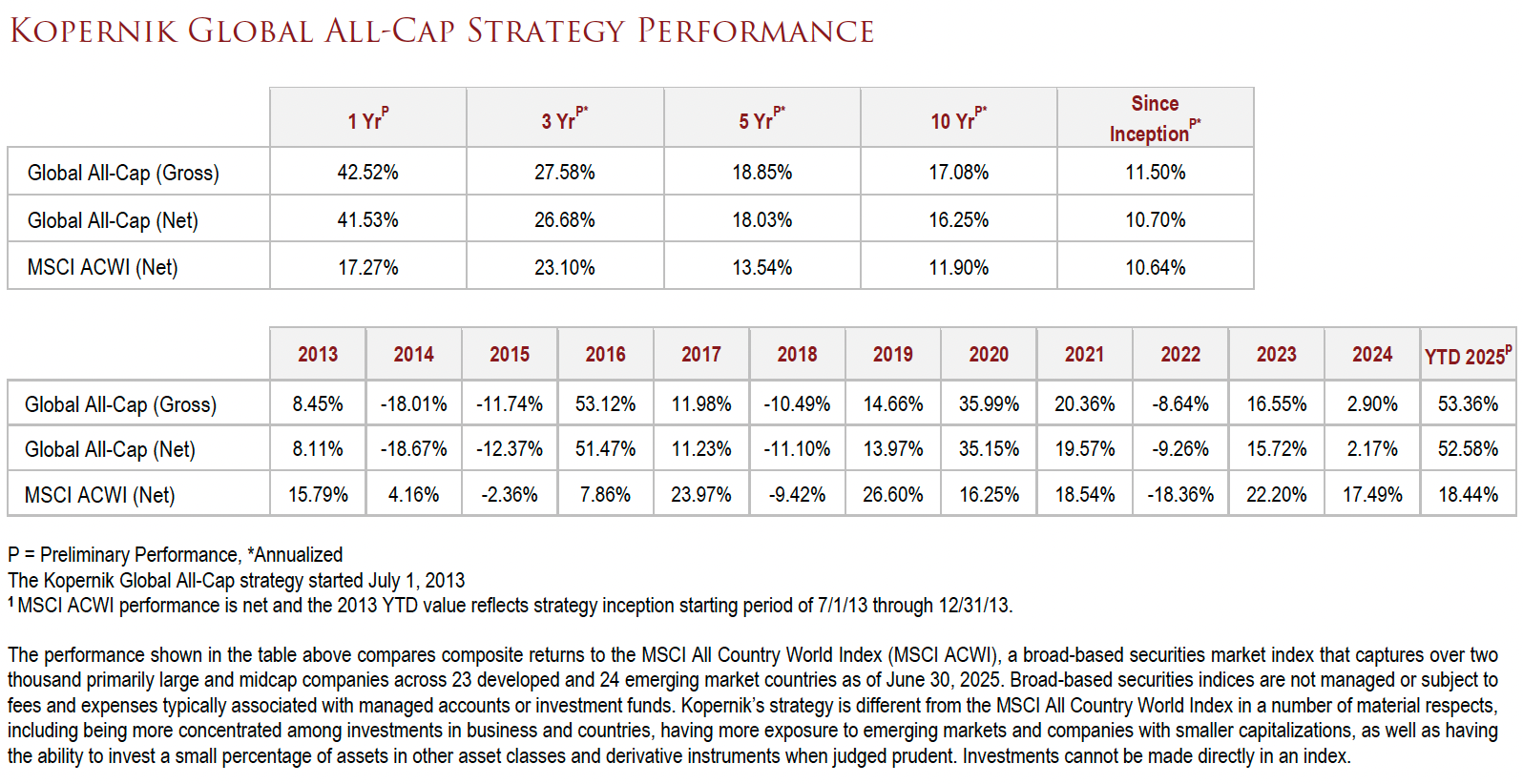

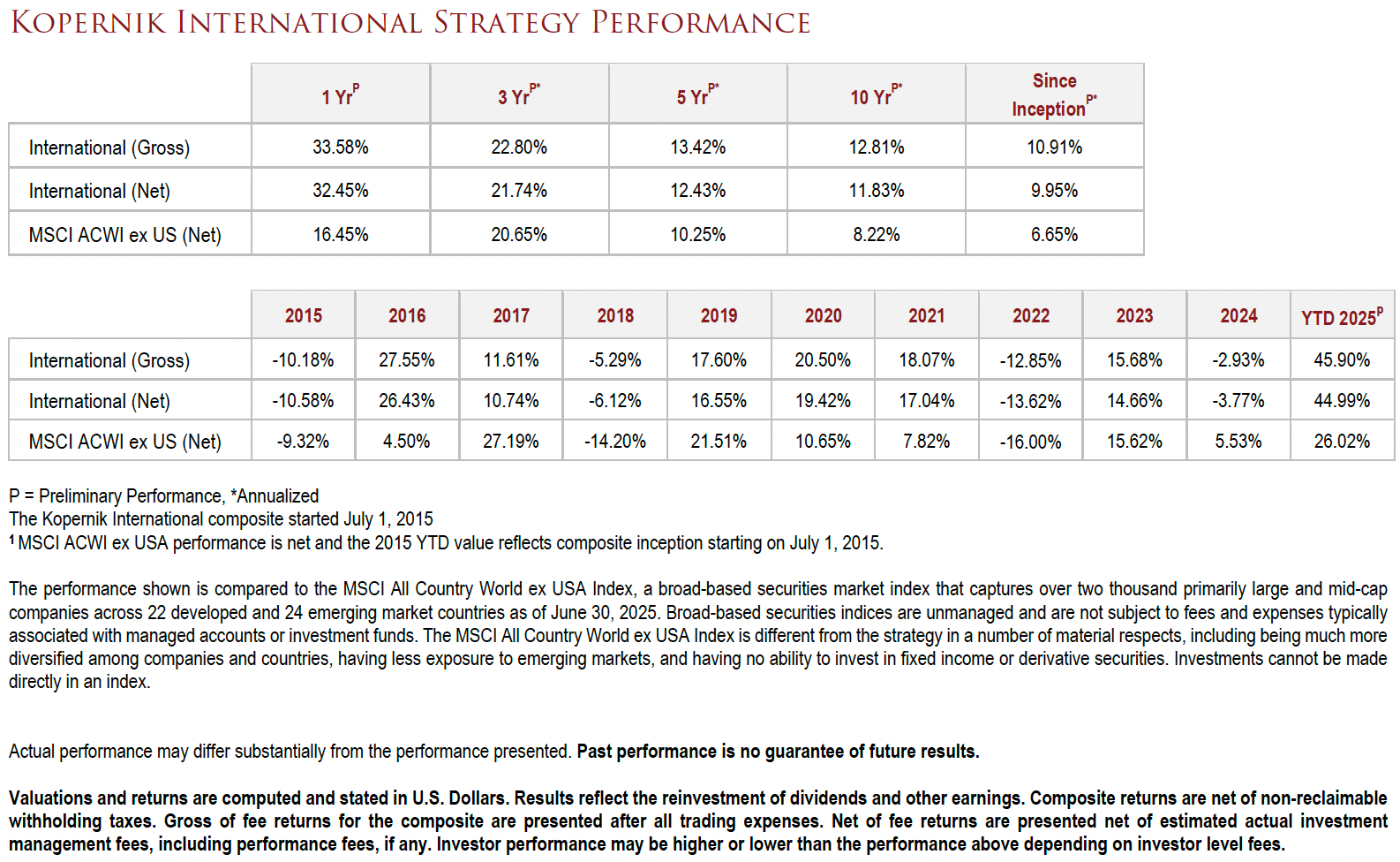

Kassim Gaffar: Thank you, Mary. I welcome everyone to the third quarter 2025 conference call. I have with me Dave Iben, our Co-CIO and Lead PM for the Kopernik Global All Cap Strategy and Co-PM for the International Strategy, and also Alissa Corcoran, our Co-CIO, Co-PM for the Global All Cap [Strategy] and Director of Research. Before I pass the call to Dave and Alissa, I’ll be providing a quick firm update.

Overall, firm assets have continued to grow. We entered the third quarter with roughly $9 billion under management. As a point of reference, we started the third quarter at around $7.7 billion. The growth in assets can be largely attributed to market action due to the strong performance across all our strategies, combined with new net inflows. It truly is refreshing and encouraging to finally see an uptick in value as an investment style. Also, we are seeing more clients and prospects reduce their U.S. weighting, or at least revisit it, and are seeking more opportunities overseas.

Moving along on the personnel side, we are now 46 employees strong, and I’ve had minimal turnover since the inception of the firm over 12 years ago. We’ve continued to bolster our research team and other parts of the firm during the year. Please note, Dave and Alissa will be referring to the presentation, which can be found on our website, kopernikglobal.com, under the News & Views section. Also, whilst on the website, you can also access several other thought-provoking commentaries and interviews by the investment team. This brings an end to the business update, and with that, I’ll pass the call over to Dave and Alissa. Alissa, please go ahead.

Alissa Corcoran: Thank you, Kassim. Hi, everyone, thank you for taking the time to listen today. We’ll kick the call off with a very exciting announcement [slide 7]. The Super Terrific Happy Day that we hosted with Stephanie Pomboy and Grant Williams last November is happening again, and it’s going to be even more super, more terrific, more happy, so please check out the website. We’d love to see you in St. Pete in February.

Okay, moving on. To say we have somewhat of an obsession with John Templeton would be an understatement [slide 8]. He is one of the investors we admire most. His description of the market cycle is spot on, and value investors, we believe, should always be asking themselves, where in the markets is the max optimism? Where are we seeing maximum pessimism? You will not find max pessimism in real estate [slide 9]. As our comic points out, real estate is located out of the price range of most people in the U.S. Incomes in the U.S. need to be at least 50% higher to afford a house.

Government bonds? [Slide 10]. While yields are higher than they were in 2020, they are still a joke, really. If you believe the stated inflation numbers of around 3%, these investors buying government bonds are willing to accept 1% yields for 10 years. If stated numbers are what many suspect to be understated inflation numbers, bondholders are actually losing money in real terms. Many today can’t even imagine higher rates, but in the 1980s, many couldn’t even imagine lower rates.

There’s also no pessimism in corporate bonds [slide 11]. Spreads are near all-time lows. High-yield defaults are higher than yields. In private credit, we’re seeing anything but pessimism [slide 12]. This chart shows the dividend recaps—that the first half of the year is on track to be the third largest over the last 10 years. With only 2021 and 2024 having higher amounts. Possibly this is where we’re seeing maximum optimism.

In equities, the global equity markets versus global GDP have never been bigger since 1950 [slide 13]. Currently, we’re sitting at 100% of world GDP. You’ll also notice that global bonds are roughly 85% of world GDP. The two combined are nearly 200% of world GDP. These are both claims on the economy. It does not seem to be a happy ending for equities. We’ve checked off real estate. We’ve checked off government bonds. We’ve checked off corporate bonds. We’ve checked off equities. The winner is—

[Song] Your Cash Ain’t Nothin’ but Trash [slide 14].

Cash [slide 15]. Institutional cash levels are at just 4%, which are levels that we saw in 2021 and in 2007. We know what happened in the years after those. If debt is negative cash, the chart on our right is also very telling. The margin debt over the monetary supply, M2, is at levels last seen in 2007. Is cash a good thing, a bad thing? Is cash trash, like our song suggests? In an inflationary environment, cash is the last thing you want to own.

This is a picture taken from Weimar Germany [slide 16]. Germany was saddled with massive amounts of debt from World War I and then additionally forced to pay reparations. Germany’s central banks turned to the printing presses to pay for this debt. Just to give you a sense of the kind of inflation that they experienced, in 1922, a loaf of bread cost 160 marks. One year later, it cost 200 billion. Just an amazing amount of inflation. The printing presses in Germany could literally not print the money fast enough.

Are we in an inflationary environment? The monetary base is up 6.5 times since 2008 [slide 17]. And Wall Street is loving it because, as we’ve discussed many times before, money printing is non-neutral [slide 18]. This is our image of the Cantillon River. Usually, when central banks first start printing money, the winners are stocks, the winners are bonds, the winners are housing. They’re the first to rise in price. The asset owners, the wealthy, win. This is the part of the cycle that many say is the “good” kind of inflation. Then, as the (water) money flows downstream, it goes into commodities and then further downstream into wages, services. This is where it starts becoming the “bad” inflation. This is where people start to worry, and this is where it starts to eat into corporate margins.

Now people are starting to worry [slide 19]. They’re starting to catch on that money printing is debasement of the currency. We’ve seen the gold and platinum, and silver prices rise significantly year to date. Google Trends suggests that people are starting to think about debasement. It begs the question: if money printing debases currency, and we’ve just seen massive amounts of money printed both in the U.S. and globally, why is our cash position high and growing? [Slide 20]. Are institutional investors right to have only 4% in cash?

From the client’s perspective, in addition to being a poor store of value, high cash levels can be a drag on performance [slide 21]. It can indicate that we are asleep at the wheel and we’re not finding new opportunities. It could make it difficult for clients who want to determine their own levels of cash. These are clearly very tough questions, topics, which is why I’m going to pass it off to Dave.

Dave Iben: All right. Well, thank you. It is interesting. We’ve made it clear that cash is a bad long-term investment. Why is our cash balance growing? A repeated theme from us is—basically, what we do for a living is take advantage of binary thought processes in the market. On these calls you hear us talk about: are international versus U.S. really that bad? Is EM [emerging markets] really that terrible when it’s the whole world? Are small caps really that bad? Was gold really worthless a few years ago and priceless now? Were hydrocarbons uninvestable five years ago? That’s what we take advantage of. We find that very few things are either a 0 or a 10 on a scale of 10. You should expect nothing less from us when it comes to cash. There is a price for everything.

How do we think about cash? We think that cash has value [slide 22]. It’s losing value quickly, but it has value. Other things have value as well. What should we do with this? If you have cash and you need transportation and run down to the Toyota dealer to look at a Camry, and they offer you one for $29,000, that’s a decent deal. I think most people would consider exchanging their cash for a Camry.

Supposing while you’re looking, they announce a flash sale, you can now have Camrys for $15,000. I think people at that point might consider buying one for themselves and one for their spouse or child or somebody else. All of a sudden, the Camry seems like a much better deal than cash. You went in looking for one, but you got two for the price of one. Now you own two Camrys, and you have $30,000 less in your bank account.

Then next week, the dealer calls you up and says, “We got caught short. We’ll buy one of those Camrys back from you for $29,000.” I don’t know about you, but I’d sell it back to them. Supposing they call you next month and say, “We’ll pay you $40,000 for the next one.” I’ll sell both. I went from having cash to owning two cars. Now I’m back to owning no cars and owning the cash again. It’s not whether cash is good or cash is bad. What is cash worth relative to what you can get for cash?

It’s interesting. People go shopping for anything, and then do they buy stuff the day before the Black Friday sale? No. They hold their cash and then they spend it on Black Friday. Only in the stock market do people want to buy more of something when it’s run up. Then hold the cash after things have fallen. That’s what we try to take advantage of. That’s cars.

[South] Korea, you’ve been hearing us talk about how much we like Korea [slide 23]. We still do, but we like it less than we did before it went up 80%. Here, instead of selling our Camrys, we’re selling Hyundai. It’s not as good relative to cash as it was when it was at way cheaper prices. People always ask, “Are you guys perma-bulls on gold?” Fair enough question [slide 24]. We’ve always said the answer is no. In 2011, we sold most of it. We still like gold, but we like it about a third as much as we did before it tripled the gold miners. That’s the way we do things. We wanted to own less cash and more gold. Now, we’re going to exchange some of that gold and put it back into cash. What to do with that cash, Alissa will get to it later.

Same thing with China [slide 25]. People hate cash. They hate China. I think there have been a couple of times in recent years when they considered China uninvestable. That’s when we were exchanging cash for Chinese shares. Now, people are starting to like China again, and we’ve turned some of those Chinese stocks back into cash. Once again, which is the better deal?

We’ve talked a lot about platinum in the past [slide 26]. We still like it, but there again, we like platinum stocks one-third as much as we did before they just tripled. Still like them a lot.

Now to get to the important part [slide 27]. This is the interesting part. Cash is a horrible long-term investment, but what about as a short-term addition, a way to add optionality to a portfolio? That’s worth looking at. It often does, not always, but often can make a rising stock do even better than if you just held it long. If one were to look at Oracle, and one were to hold just Oracle versus rebalancing 80% Oracle, 20% cash, this has gone up so quickly that yes, the cash did not help. It was a cash drag. That was what people suspected it is. Maybe cash is bad, but not everything performs like Oracle has recently.

Novo Nordisk was all the rage last year, but it ended up going nowhere [slide 28]. It went up 6%. A month ago, it was actually down. There, by rebalancing all the time, you could have added more than a percent to your return. Not a bad thing to do. People have it in their mind, things go up [slide 29]. What’s going up more than the Nasdaq [100 Index]? Clearly, holding cash must be a bad thing if you could have held the Nasdaq instead. Interesting, if you hold it from 1999, you added a lot of value by holding 20% cash over the bear market. But then you go a longer cycle, you still added a lot of value over the next seven years. 15 years, that’s a pretty meaningful period of time for an index that was doing very well. You actually did better by rebalancing into 20% cash all the time. Now, this is interesting to me. A quarter century of maybe the most breathtaking bull market in the history of mankind. If you were rebalancing to 20% cash, yes, there was a drag. Barely 57 basis points. I seldom see a bear market like you’ve seen on the Nasdaq. Yes, I think cash quite often helps, and it doesn’t hurt as much as people think.

To delve into that further, we’ve shown you this a lot; probably in the future, we’ll continue to show you this a lot [slide 30]. Volatility is a good thing, and cash provides optionality to take advantage of that. This shows that a stock that’s gone nowhere can actually make a lot of money if some people use cash to capture that volatility.

To look at that, we own a stock that did pretty well in the early years and has since gone nowhere for the last half dozen years, and yet it’s our best performing stock in our portfolio over the last dozen years [slide 31]. That is because we were able to use cash to add and then raise cash later when it fell. What does that add up to? That adds up to almost three times the annual performance of just holding the stock long [slide 32]. Cash can be very additive.Also, cash can be very additive as we’ve just shown in a bull market, but what about in a bear market? It’s imperative to have some cash in a bear market. Some people still think that’s a possibility. We think the market continues to be cyclical [slide 33]. As Charles de Vaulx pointed out, even when stocks are cheap, they can drop, and the markets are a volatile thing, but what about when stocks are expensive? [Slide 34].

Here is a chart showing that when markets were almost as expensive as they are now, 1929, 1965, 1999, those were very bad times to be too far out over one’s skis. We think people should not be as phobic of cash right now as they are. I think that optionality and the ability to take advantage of dips will be more important than ever.Let’s explore more about cash [slide 35]. Some of you know Bob Rodriguez. I’ve known him for many decades. We’ve gone to lots of meetings together, including serving on the USC Student Investment Fund board together for a lot of years. Interesting guy, really smart guy, and notorious for his high levels of cash. He held his cash during a 25-year period where it was a pretty strong bull market, from 1984 to 2009.

How bad did that cash hurt him? He had the number one fund in America for the quarter-century. He did well with cash. We’re not talking 8% cash. We’re talking 44%, something like that [slide 36]. With that kind of cash, and probably on average 20-something odd percent cash, 15% versus 11%, he didn’t have a lot of small stocks. 600 basis points, better than most of the small stocks. Cash used as part of a process can add a lot of value even when it’s losing value [slide 37]. It’s likely that down drafts are on the way. Either way, having 5%, 10%, or 20% cash is not something that people should fear. They should welcome the optionality, we think.

Let’s reiterate some of what we’ve already said [slide 38]. Cash is not a good long-term investment. It’s an awful long-term investment. I think in my lifetime, it’s lost 98% of its purchasing power. If someone had a stock that lost 98%, people would say, I was wiped out, I lost everything. If people say the dollar probably in the next 30, 40 years will lose all its value, people will say that’s hyperbole. No, it’s not. It happened in the last 50 years; it’ll happen again in the future. Don’t confuse this with us saying cash is an investment. It is not. It’s a residual and important part of an investment process. It offers optionality with a very long expiration date. It gives you an option on every other asset class but cash, and with the strike at your choosing.Now, yes, it is very important. Not meaning it’s comfortable for everybody. A lot of people don’t like it. Jean-Marie Eveillard, another friend of mine whom I respect a lot, he’s always said, “I’d rather lose half my clients than half my clients’ money.” That’s a guy of high integrity, I think.

Digging in a little further on this, before Alissa talks about the important part of the future and the past, how has cash helped us? I think famously, we were six years too early on uranium [slide 40]. Fortunately, having some cash allowed us to keep averaging down and to maximize our position right at the bottom. That allowed us to do well. We were fortunate. It turned out to be a good investment, even over the 10-year period that included the six years too early.

Before leaving this, we’ve been talking about how cash has whatever value it has, and what’s important is how is that value versus other options. We also look at gold that way. The dollar is one thing. Gold is real money [slide 41]. Why should gold not be viewed the same way as the dollar in terms of we should like gold less when other things drop relative to gold, and we should like it less as other things go up relative to it. That’s what we do. That volatility allows us to take advantage of that. Uranium became kind of expensive relative to gold in the past. We didn’t own it. Uranium became cheap relative to gold. Over that period, we were buying a lot.

We should look at things relative to dollars, and we should look at things relative to gold [slide 42]. Doing that has allowed us to, in a market that’s been frustratingly tough for value stocks and for commodities – they’ve all been left in the dust – volatility, optionality, and the ability to go in and out of money into things has allowed us to do a lot better than just a buy and hold strategy and these sorts of things.

Continuing with that, it’s worth talking about gold versus other things [slide 43]. If people think that buying us is owning a gold fund, we are now a single-digit percentage of gold now, which is a big change from where we’ve been in the past. We still have things of real value. Just a few months back, platinum would have had to triple to catch the gold price. That’s something that’s rarer than gold and usually sold at a premium. To have things like nickel hitting lows, like gold hitting highs, are things that we need to take advantage of and plan to keep taking advantage of.

It’s served us well that people’s opinion of platinum relative to gold and other things has changed over time [slide 44]. That’s allowed us to buy Impala Platinum [Holdings Ltd], sell it later at higher prices, buy it back again at lower prices, and trim it recently back at the higher prices. There again, metals have had a tough 15 years, but we’ve been able to use this volatility, optionality to do twice as good as gold and three times almost as good as other materials [slide 45]. Cash and optionality can be useful.

We talked about China being in and out of favor [slide 46]. When it was out of favor, it allowed us to buy arguably one of the better utilities on earth, cheap, clean, carbon-free, green electricity with CGN [Power Co Ltd]. There have been a couple of times where because of people’s views on China, they thoughtlessly sold a good thing at a cheap price. That, along with the Eletrobras that we showed you earlier, has allowed decent returns on utilities during that time when utilities haven’t done that well [slide 47]. Now, as I transition, even though this sounds like a dad joke, it was contributed by Alissa [slide 48]. I will hand the mic over to her, and she can tell us about why we feel good about the portfolio going forward.

Alissa: Thanks, Dave. We’ll start with the gold miners, which are top of mind for many investors [slide 49]. I actually got a text from my dad asking me about gold miners today, and I think he’s on the call. It’s definitely top of mind for a lot of people. The GDX [VanEck Gold Miners ETF] has rallied 130% year to date. As Dave pointed out earlier, we like them less. We’ve trimmed our exposure quite significantly. We’re down to 8% in gold miners today. We still see upside, as this chart shows. Gold miners could double, and we would just get back to the long-term average of gold to gold miners.

However, as Dave alluded to, we’re seeing even more upside in the industrial commodities [slide 50]. Copper to gold, iron ore to gold, manganese to gold, nickel to gold, all of these are at 30-year lows. We’re cashing in our gold mining and trading them in for miners of other things, other things of real value.

We’re far away from the max optimism in mining [slide 51]. The mining industry globally just makes up 1% of total global equities. Compare this to 11% decades earlier. As an example, Glencore is one of the largest mining companies in the world [slide 52]. Despite the fact that the money supply has doubled since it IPO’d in 2011, the price is actually lower than it was in 2011. This dynamic is even more pronounced with Vale [slide 53]. This is the world’s largest iron ore miner based on reserves. It’s a huge nickel producer also. This was a $40 stock in 2007, and now it’s $10 a share. Meanwhile, the money supply has gone up six and a half times from that time period.

Moving on to energy [slide 54]. Oil relative to gold has rarely been cheaper. It’s only been cheaper once in 27 years. Oil companies are very attractively priced. Petrobras [Petroleo Brasileiro SA] is the largest oil company in Brazil [slide 55]. It’s amongst the top oil companies in the world. It has some of the lowest-cost oil assets in the world. It’s trading for five times earnings and one times book value, cheap on reserves and resources.

Outside of resources, international conglomerates trade at a very healthy discount to book value [slide 56]. Some are single-digit earnings [slide 57]. Within conglomerates, one of our fund’s larger positions is in LG Corp, which trades at a significant discount to just the sum of, you could buy LG Chem, LG Health, LG Uplus, blanking out on their other subsidiary, but you could buy all four of those companies in the market, or for a 48% discount, you could buy the parent company, LG Corp. As you can see, this company has not kept up with the rest of the Korean market, trading at 40% of book value.

Asset managers are trading below 1% of their AUM [slide 58]. We think that asset managers maybe should be trading around 2.5%. These are extremely depressed multiples to their AUM for these sorts of franchises.

There’s even some opportunities in U.S. health care [slide 59]. Centene is one of the largest Medicaid managed care organizations in the U.S., with a 20% market share. The stock collapsed, and we took advantage of the cheaper price, and it is now something that you could buy for eight times earnings and 60% of book value.

As the theme of the call is trims and adds, as you can see, we did a lot of trimming and a lot of adding [slide 60]. In general, we trimmed Korea early in July, and then throughout the quarter, we were trimming gold and uranium. Meanwhile, we were spending that cash on a broad set of opportunities. Some newer opportunities were asset managers in Europe. Centene, as I mentioned, is a healthcare company. Several companies exposed to iron ore, potash companies. We bought SLB, which is Schlumberger, the world’s largest oil service company. Teleperformance. There’s lots of opportunities. It’s a very exciting market for active managers.

Here are our portfolio characteristics [slide 61]. This is the model portfolio. This does not include Russia. Still very cheap on book value. If you include Russia, we’re much cheaper on earnings [slide 62]. This is the main difference here. Here are our metrics for the International portfolio [slide 63]. Still much cheaper on most metrics, as you see [slide 64]. You can tell we are still very different from the index [slide 65]. Very little exposure to the U.S. High exposure to emerging markets. That’s where we see most of the opportunities today.

[Song] Your Cash Ain’t Nothin’ but Trash [slide 66].

Those [the songs] are Dave’s ideas. To conclude, cash is a residual to our very disciplined investment process [slide 67]. We don’t feel the pressure to be fully invested at all the time. Rather, we let the prices of stock dictate whether or not we’re interested in using that cash to buy stocks. We agree that cash is a horrible long-term investment, but we also have shown that it provides wonderful optionality in the short term and can increase and help returns, especially during bouts of volatility, which, as equity investors, we should be expecting.

Investors often hold cash at the worst times. They often hold too much cash at the bottom of the cycle when they’re fearful, and they often hold too little cash at the top of the cycle when they feel the pressure to be fully invested. While our cash levels are more elevated, we still have 85% of our portfolio invested in very high-quality companies and trading at extremely attractive levels. With that, we will take your questions. Thank you very much [slide 68].

Mary: All right. Thank you, everyone. Again, if you have a question, please type it into the Q&A box. We’ll do our best to get to as many of them as we can. We love to take your questions, and I see them coming in here, so very exciting. I do want to mention just briefly, we tend to get a lot of questions on similar topics, so I will frequently group those together thematically. If you don’t hear your exact question being read, that’s probably why, but if you would like us to follow up with you, absolutely, please get in touch, and we’re more than happy to continue the conversation.

Let’s just start with a question that we’re getting a lot from our clients and from prospects, and that’s, we’ve had very strong performance this year, and so have investors missed it with us? We get that question a lot. Why now? Maybe, Alissa, you want to go first.

Alissa: Sure. Definitely, our portfolio is less attractively priced than it was, somewhere last year. However, we still see about 130% upside to our [Kopernik’s estimates of] risk-adjusted values in our portfolio. Then also, we mentioned that these cycles, these things that we’ve been investing in, they’ve been out of favor for a long time, and these cycles are decades long. We went through that in a prior presentation. Emerging markets, small caps, commodities–these have been out of favor for a very long time. Then our process, you’re buying our portfolio, but you’re also buying our team and our process, which is continually finding new investment ideas. We will be rotating into other things that are dropping or having more upside.

Dave: Having done this for a long time, I can say the late 90s were a painful time for value investors. Then we did really well in 2000 and really well in 2001 and really well in 2002. When the market turned up, we even did really well in 2003. Then this one big institution said, “All right, well, now I’m going to give you a bunch of money.” I was thinking, “Why? He had missed it”. But he did not. We had a dozen years of doing really well, which is what can happen when value underperforms for a long time. Value has underperformed for the longest time in history. To think the three good quarters are the end of something that’s a decade and a half depressed is probably a mistake. The potential is there. We have talked about how cash is not a good long-term investment. A lot of other things, as we’ve demonstrated earlier, are overpriced. Yet value stocks still have 100 and some odd percent upside from here. I would think people would want a percentage of their portfolio to be in something like that versus the alternative. They missed the first 50% move. Hopefully, there’s a lot more to come. We’ll see.[1]

Mary: We have a lot of questions coming in, which is great. As they tend to do, I tend to group around different themes that we’ve talked about. I want to actually start with energy. We have a couple of questions. We didn’t really mention natural gas on the call. Talk a little bit about our thesis on natural gas and any opportunities that we might be finding there. Dave?

Dave: Yes. One thing that we’ve always liked about energy is that people seem to sometimes prefer gas to oil and sometimes oil to gas. Sometimes they like coal better, and other times they hate coal. Sometimes they like electricity. Other times, they like wind and solar. It doesn’t always make sense. Natural gas has been so much cheaper than oil in recent years. Briefly, not in 2020, but natural gas is where we have been finding the value. To have things like Range [Resources] go up 20 times and we still own it, that just shows how cheap it is, although it’s still not where it was a decade ago.

We like gas because it’s cheaper and cleaner than many other forms. The U.S. has a competitive advantage. The U.S. and Canada. We like that. We continue to find things that we might add to the portfolio as well. We’re talking about volatility. We’ve also trimmed and added to our Range and others pretty well over the recent years, we think. Oil, as I mentioned, was a lot more expensive than gas and still is, but oil has been coming down. Don’t be surprised if you see oil starting to find its way back into the portfolio, but we certainly like gas.

Mary: You actually just anticipated the next question I was going to ask, which was about oil, particularly oil services, offshore drillers. What are we seeing there? Maybe, Alissa, you want to expand on that one a little bit.

Alissa: We bought a drilling company, Borr Drilling. We were excited to see some of that, and it’s bounced quite significantly, so now we’re trimming. We recently bought Schlumberger, which is one of the– well, I guess, it’s SLB now. One of the best oil service companies in the world, and a very high-quality company. This is a company where basically the revenues haven’t grown for a decade. A lot of the energy growth has been in the U.S. shale. This is not really relevant for SLB, and oil is very depressed. This was a stock that was just $60 a share in 2023, and now it’s in the low $30s. This is an opportunity to buy a very high-quality business at a very good price.

Dave: To add to that, people who have been with us a long, long time, in 2002 and 2009, we had opportunities to buy stocks, but realized that the bond market would offer us a better deal on the same company, and that we bought convertible bonds and double-digit yields, equity-type returns. That turned out pretty good. There hasn’t been much opportunity recently, but with Borr Drilling, we made money on the stock, but still hold the bonds that we were able to buy opportunistically. It’s one of those rare times where we get equity-like returns on a senior security.[2]

Mary: Continuing on our energy theme, we have a couple of questions about uranium, but not about the uranium miners. It’s more about nuclear energy and nuclear utilities. The question is, what’s your stance on the potential of utility companies with nuclear energy growth potential? Have they already run too far, essentially? It’s almost a two-part question in there, maybe some of these more undervalued utilities that we’re finding in places, and then maybe mention also the comparison with that in the developed world.

Dave: There’s been several times in the past where we’ve shown you CGN [Power], which we just showed you relative to the U.S. nuclear things, and CGN is way cheaper, which is almost counterintuitive since the Chinese have done a great job of building quality nuclear reactors under budget and on time, where the U.S. and Europe famously build them at four times the cost, over budget, and over time, and so it’s backwards. Whether the U.S. utilities are worth it or not, reasonable people can disagree, but I don’t know why in China and Korea, and elsewhere, they’re still on sale. We’re happy to take advantage of that.

Mary: Growing.

Dave: Growing faster, yes.

Mary: What are your thoughts on the data center power needs? We have that question as well.

Alissa: I mean, smarter people know better than we do, but it seems like there’s a lot of money being thrown at that, and up until, I guess, today, all these AI companies are being rewarded for competing on a higher CapEx number. I think that we will find that, like ’99, some of this capacity is going to be obsolete.

Dave: At various times in the past, we’ve talked about ESG and how we, like everybody else, want better governance and better environment, you name it. We’ve found it interesting that people view the people providing power as bad people, that the people consuming more energy than has ever been consumed in the history of mankind to be good ESG citizens, is beyond us. In addition to that, who wins the AI game remains to be seen, but the energy producers, they’re clearly winners. We’re happy to own the nuclear and the hydro and whatever else it takes to fill the insatiable need. I think we can win from this AI trend without taking anywhere near the risk.

Mary: For the moment, that does it for questions on energy, but that does not mean you cannot ask another one. I will absolutely circle back if you do have another question about energy, anyone on the call. Let’s move to–we have a single question about pharma. We talked about Centene, but thoughts on pharma, especially large pharmaceutical companies.

Alissa: We saw Novo Nordisk up and down, but the high price for Novo Nordisk was 10 times sales. This is a very, very, very high valuation. As they’ve corrected, are we seeing any upside? Still no. There are some select opportunities as in Centene and maybe other managed care companies, but we’ve not necessarily seen it in the U.S. pharma. That doesn’t mean that we aren’t seeing it in other countries. We have a Korean pharmaceutical company. We have a Japanese pharmaceutical company. There are some select opportunities in that space.

Mary: We have about 13 open questions, and I think about 12 of them are about gold. I’m going to do the other ones first, and then we’ll circle back around to gold and precious metals in general. The next question, we have a couple of questions specifically about European stocks. I think lots of folks know that we spent some time in Europe this summer doing research, which was fantastic, but then also they’ve seen a lot of European asset managers. We mentioned, I think, Schroeders, on the call. A question specifically about how we evaluate the mid- to long-term prospects for these European asset managers, and what do we see going forward for them? Dave.

Dave: European asset managers, U.S. asset managers, we view them as businesses that aren’t perfect. There’s a lot of competition. A lot of them have bonds, which are claims on these dollars that everybody hates, so they’re probably going to lose value over time. They’ve not been something we’ve owned a lot of over the last 30, 40 years. They have good franchises, many of them. They provide needs that people want, and for that, they charge a fee. The fees used to be too high, and now they’re reasonable, if not low. And everybody is assuming they’re going to go to four basis points, but the four basis points are being charged by index funds; we think that those are just commodities that aren’t worth four basis points, in the long run, would be our view.

Passive-active is a cyclical phenomenon. We’ve talked about passive is self-fulfilling for a long, long time, and then eventually must regress to the mean. It’s happened over and over in time. When that happens, I think people will lose their fear that active managers are going to have to see their fees go down to four basis points. Alissa already talked about how things that generally sell 2% to 8% of assets are trading at 0.8% of assets now. If I’m wrong and the fees keep coming down, we’re probably okay anyhow. That’s how cheap these things are selling at. If this trend from passive to active once again happens, these things have nice potential. If not, there shouldn’t be that much downside. The question was Europe. I think Europe, the U.S., Asia – it’s all the same.

Mary: From asset managers to industrials, what do we think about European steel and European steel companies? Dave.

Dave: We’re not top-down, but it’s not an area where Europe has that much of a competitive advantage anymore. For decades, they had high quality, which was good, but you can read lots and lots of articles about whether Europe should or should not be imploding their industrial economy, but they haven’t. In general, steel should be owned at places that have lower energy costs and more access to raw materials and whatnot. You’ll find both of those more in emerging markets. We don’t generally own a lot of steel anyhow. If we did, we would probably want a bigger margin of safety in Europe than we might want in some places, but they have quality companies.

Mary: Speaking of emerging markets, we have a question about Argentina. I think it’s been in the news this week quite a bit, so it’s probably on people’s minds. Again, we spent some time there doing research a couple of years ago. Thoughts about Argentina, the move out of maybe a more socialist-style government, growth potential. Valuations there seem incredibly low, according to our questioner. Would you agree, and are we looking there?

Alissa: We have one Argentinian company with Cresud, which they were cheaper, and now they’re not as cheap because the whole market reacted very positively to the recent election. They’re still cheap, but we’re also still talking about Argentina, which is still a basket case and still has a lot of work to be done. We’ll see if Milei can turn it around and stay in power. It seems like some of the stuff he’s doing is working. Inflation’s come way down. Brazil, all these emerging markets, we use a very big margin of safety. Argentina, we use a very high one as well.

Dave: People joked how many years ago, not that much, when they had defaulted seven times in a century, and yet they were able to issue a 100-year bond if people accepted for again, I can’t remember, 7% or 8%, and two years later, whatever, it’s in default again. We’re very encouraged by what’s happening, but only a fool would assume that there’s no risk to this. We want big margins of safety. We talk about how the U.S. and Canada have a competitive advantage in gas. Argentina is one of the few other places on earth where the technology is working, the shale and whatnot. They have some of the best farmland in the world. If they can succeed in getting a single currency without this horrendous off-rate thing that really hurts the resource companies and kills the agricultural companies, the upside potential is huge.

Mary: One more geography question that just came in. How do we view Japan versus Korea at this point? Alissa.

Alissa: Japan is still so much more expensive than Korea. Korea is starting to perform as we showed. We had 18% of our portfolio in Korea at the beginning of the year. Now that’s down to 15%. We’ve been trimming back many of our positions. They’re very similar. They compete with each other. Japan’s been on a long bull market at this point. We have talked for a long time about how Korea could follow the Japanese market. I think it seems to be just starting now.

Mary: Dave, do you have anything you want to add to that?

Dave: I’ve followed Japan for a long time. I was shorting it in ’89, ’90 because it was one of the most colossal bubbles ever. After it dropped for 20-some-odd years, 13 years ago, we had 25% of our portfolio in Japan. It was really hated. Abe won, and the market went nuts, and we sold down a lot of it. Everybody hated it then, and everybody would invest in Asia ex-Japan. That was the thing. Nobody wanted to be in Japan. Their market bottomed in 2012, I think. Now people talk like it’s coming off the bottom now. It’s reasonably valued. There are some cheap stocks in Japan and some not cheap. We like Japan all right.

At the bottom in 2012, all the things they loved about Japan in ’89 were the very same things they hated about it. Government participation went from a good thing to a bad thing, and long-term time horizon went from a good thing to a bad thing, and the family ownership, and good thing to a bad thing, you name it. I think Korea is right where Japan was in 2012. Everybody views it as a bad thing that the families have all their money in these things, and a bad thing that they’re willing to invest for the long-term, even if it’s for short-term profits. The complex nature is a bad thing, but it’s priced in. And Japan’s made a few positive steps that have been rewarded. As Alissa said, the Koreans, well, I’ll tell you that they haven’t missed that fact.

Mary: All right. Moving on to our numerous questions about gold and other precious metals. I’m just going to start at the top, and we’re going to go down. The first is a question about Seabridge [Gold]. Do we believe that Seabridge will partner up this year, and what might such a deal look like?

Alissa: We can hope, but they’ve been saying that for a while. Now it does seem like the gold companies have money to spend, and so it’s likely that they would be looking for reserves. They need to replace the reserves, and that’s always been our thesis, that the big miners are going to have to find these junior miners that are sitting on huge reserves. Seabridge definitely qualifies in that camp. One can hope.

Dave: Newmont owns property around the area. They’re logical, but they’ve never said there’s any interest. I think we do a good job of buying things too cheap and a terrible job of telling you when it might be realized. We won’t guess whether it’s going to happen this year or not, but it’s inevitable someday.

Mary: A little bit of a question about portfolio weightings. You mentioned we’re down to 8%. Gold miners, where are we in platinum, and also where are we in uranium.

Alissa: We’re about 7% in platinum. Uranium, I’d have to add that up. I think we’re about 6% uranium. That’s a combination of both the physical and then—[NAC] Kazatomprom and Paladin [Energy].

Dave: 8% gold might seem low since we’re under 20s, but I think if any other manager on earth had 8% gold, their clients would say, “Are you nuts, calling that much?” Most people have less than 1% of the last stats I’ve seen.

Mary: We actually have a materials weighting specific question for International, so I want to make sure that we get to that. The question is, you show a 30% materials allocation in your International Fund, having traded largely out of gold while raising platinum and other metals, as we discussed. Again, we’re not going to predict what our materials share of the portfolio may become, but what opportunities are we seeing there, and what’s the role of copper in International in particular, but also in GAC [Kopernik Global All-Cap]?

Dave: I’d say, in recent years, we’ve found so much value in these smaller companies, big resources, small companies, especially in gold. Those were things that International couldn’t partake in. Nowadays, we’ve talked about that’s changed. One, all the stocks are up. Now, these big conglomerates are more interesting than some of the gold companies. That means International can fully participate in this. I think International and GAC might start looking more similar in the materials space.

Alissa: You saw companies like Vale and Glencore, Ivanhoe Mines, things that are big, and absolutely International’s going to participate.

Dave: As far as the copper part, tell me the future. We’ve seen the last five years, everybody hated copper, so we bought it, and then they loved it, so we sold it, and then they hated it again, we bought it, and they loved it. Copper, we’ll see what people think next month.

Mary: That’s an accurate statement. All righty. Again, just going down the list of questions here. Given gold has risen so much, gold price is up significantly, to say the least, are gold miners cheaper today than they were six months ago?

Dave: No, because we all along have thought that there was different ways to value gold. We look at prices, incentive prices, but we’ve also looked at money supply and shadow gold price. Actually, our target price of gold has gone down the last couple of years because the money supply shrunk. We all know it’s going to go back up in the future, but we don’t put that in our models. We’re pure bottom-up. The stocks have tripled, and our theoretical value has gone down. They are not cheaper the way we look at it.

Mary: When you say platinum may get back to parity with gold, this questioner reminds us about the supply disruptions the last time, platinum and gold was a little bit closer to parity. South Africa, Russia being the primary suppliers, Eskom [state-owned public utility in South Africa] had pretty severe outages. Do you think that platinum and gold can get back to parity without another supply shock?

Dave: Yes.

Mary: Okay, there’s our answer.

Alissa: I wouldn’t be surprised if there was a supply shock. We’re talking about South Africa and Russia.

Dave: Platinum is scarcer. Often sold at a premium, not just quite supply stock.

Alissa: The charts that we’ve shown have been over 125 years, so there’s lots of times where all of this above or at parity of gold.

Dave: People are going to know if there’s a big supply shock in terms of South Africa, for whatever reason, not able to deliver the platinum. That would be very good for platinum, but not good for our stocks, so we should be aware of that.

Mary: That’s true. Are the industrial metals to gold ratios, are those low because industrial metals are out of favor or because gold has soared, or both?

Alissa: Both.

Dave: Both, and back to our Cantillon River thing that we like to pound on people. People are starting to suspect that a massive devaluation of currencies is coming. Just like we saw in 2020, the money went straight into gold, then very quickly rotated out of gold into the other things. This might not be as quick, but you’ve got 100 years of history and logic to suggest that if the dollar is losing its value and the euro is losing its value, is it really losing its value to gold but not losing its value to copper or nickel or platinum? It’s losing value to everything, healthcare costs, restaurant prices. To think that it’s only gold that’s going up relative to the dollar is a mistake. It’s just a matter of how fast the waves go down the river, we think.

Mary: We have one more specific gold, well, sorry, two more at the moment, specific gold questions. I love these questions because one of the things we do so much of is reading. You quoted numerous other people in this presentation, people that we think are smart and people that we think are thoughtful. I really like it when people ask us if we’ve read something. It’s one of my personal favorite questions that we tend to get. The question is, I understand gold has increased in price. Hence, you desire to trim. That said, have you seen Luke Gromen’s work on changes to the monetary landscape and the reasons he presents why gold is in a paradigm shift and not just a cyclical rise? Does this affect our thinking at all?

Dave: We, I think, agree with a lot of what he says. Don’t get us wrong. In the long run, gold’s going to go to infinity, right, currencies always go away. The point that, hopefully, we’re making clear, we like gold. We still like gold. We still have 8% of the portfolio. Nobody else does, I think. We are saying that why he’s going to be right and gold’s going to go probably a lot higher, we suspect that copper and nickel and platinum will outperform relative to gold.

Alissa: Also, it helped our performance a lot to trim gold in 2016 and to trim in 2020. It wouldn’t surprise me if we saw some sort of correction in gold. Nothing goes straight up.

Dave: Even this year, who knows what happens in the end. Since we rotated that gold into platinum, platinum’s done better.

Mary: We talk about incentive prices when we value a lot of these things that we’ve been discussing, uranium, platinum, and gold. We have a question about what those incentive prices are. If you’re new to us, an incentive price is what it costs to incentivize new production. To get the stuff out of the ground, and it’s an important component, one component of our many scenarios in our models. Maybe, Alissa, could you talk a little bit about what the incentive prices are for uranium, gold, and platinum?

Alissa: Gold, I think we’re using something closer to $3,000 an ounce. We’re above that. It’s not a price that is exact by any means because there’s so many things that go into it. For a long time, we were using $2,000 an ounce. Then $2,000 an ounce, they still weren’t building mines because inflation had come in and the amount that they would have to spend on their CapEx rose, labor rose, and commodity prices rose. I would suggest that probably platinum is in this similar range. For uranium, a lot depends on demand. It’s a very, very steep curve at the far right of it. It could be $75, it could be $125. It’s a very wide range depending on where demand goes.

Dave: To add to that, you said it’s the price that it would take to incentivize people to mine. It’s a price that would incentivize it to come on-stream as fast as it’s needed. Like Alissa was just saying, there are people that can bring uranium on at $30 to $40. If they’re going to keep building these reactors and demand comes, as we’ve said, you can supply some at $40 and some at $50 and some at $60. For current demand, it’s probably $100, $125 is what it would take to bring it up fast enough. If they build these new reactors, it’s steep. It could be $200. If that sounds crazy, it’s been 16 years since uranium was $137 a pound. That was many years ago. There’s been a lot of inflation since then. If somebody says $70 is the right price, they might be right. If someone says $170, they might be right too.

Mary: All right. Quite a few more questions. About six more at the moment. We’re going to shift a little bit into some bigger picture, our industry, investment industry questions. We have two questions about other types of – one about private equity and one about hedge funds. Let me just read the question. Anecdotally, more hedge funds are allocating to similar industries, sectors, themes, and names to the ones that we are currently focusing on. They’re doing that more today than they would have a couple of years ago. Do we consider hedge fund crowding as a thing and our concern in our investment decisions?

Dave: Yes. I think that maybe five years from now, that could be a problem, where we can welcome our stocks will be way, way higher by then. The fact that some hedge funds and private equity guys are starting to do this, I’ve been wondering when that would happen. What we do, I think, is natural for a private equity fund. In the past, the private equity funds have done what they ought to do. They take cash flow and they lever the hell out of it. It works. When interest rates have been dropping for 40 years, that works really well.

Now, we’re buying things and we’re saying, “We think it’s going to go up 10 times in value, but we don’t know when.” That’s a risk for us because our clients can take the money out tomorrow. That is not a risk for a private equity guy. If I were running a private equity, I would not be chasing these minuscule cash flows. I’d be buying these things. They’re going to go up 10 times. I got the money locked up. Your IRR is going to be really good. Right now, as you’ve said, they are starting to do this. Once we’re hearing about how every hedge fund and private equity guy is loaded to the gills with what we own, then hopefully, you’ll find we don’t own that stuff anymore.

Mary: Yes, exactly. Our last four questions circle back to the overall theme of our call, cash and how we use cash. We referenced that at the end of the current cash level at approximately 15%. The question is, what was the highest cash allocation percentage and when was that? Conversely, what is the lowest cash level?

Dave: Lowest is zero. In 2020, that happened. We couldn’t buy something without selling something else. Highest, it depends. I’m not counting cash inflow. If somebody puts money in the fund, it goes up. I don’t know. It’s probably been 15%, 16%, 17% in Global All-Cap now, it’s been about 30% in International. I’ve been doing this for 44 years. There was a time in 2007 when my Small-Mid Fund went up to 23% cash or something. The market, fortunately, crashed right after we put it to work right away. It depends.[3]

Then over the years, generally, 0 to 10 is where it runs. This is, by almost any metric, the most expensive market in history. We’ve been putting money to work pretty quickly, but when you have to Korea up 50% and mining stocks up 100%, the cash level has to go up. As [the weight has] suggested.

Mary: Another question about cash. Is there an element of timing in us raising cash, meaning that we’re anticipating something? How otherwise would you explain trimming Halyk Bank while acknowledging that the price has gone up, its fundamentals have also improved, and it remains crazy cheap? Alissa, or Dave, or both?

Dave: Halyk Bank, like anything else, the more it goes up, the less we’re going to want to own it, so we’re going to trim it. I think they are in a class above most banks, but banks are a cyclical business. If you look at banks on a P/E [price-to-earnings] basis, usually like 2007, these P/Es were very low in banks, and people were about to lose almost all their money in banks. I don’t think that’s going to happen to Halyk, but the time to buy most anything is not when they’re hitting on all cylinders. It’s after the problems happen. It’s just, let’s identify it’s a good bank before people realize it, and once everybody realizes it, let’s take some chips off the table. The first part of the question.

Alissa: Oh, no, I’m glad they asked that question because we’ve not—our cash levels absolutely not trying to—there’s not a cash target and saying, “Okay, we’re raising cash because we expect some sort of downturn.”

Dave: Never ever.

Alissa: It’s entirely just residual to our trims and adds, and when we’re finding the opportunities.

Mary: All right, two more questions. We can’t get away from a conversation about cash without asking about the put option. Do we currently own any put options, and in the present environment, what are our thoughts on that?

Alissa: We do have some put options. Well, one expired, and we have one more expiring at the end of November.

Dave: Just to reiterate, it’s all about price. It is, just like with cash, we’re never guessing that the market is going to go up and down. We know that it does go up and down, but we don’t know when. When put options get cheap, we buy them. It’s important they’re cheap because you’re going to lose your money most of the time. When you make money, you need to make a lot of money, and that only happens if you bought it too cheap. Lately, they’ve been too expensive for us to buy. Every now and then they tease us a little bit that they’re going to get cheaper somehow, but they have not, so that’s why we only have one left.

Mary: All right, our last question today. Again, thank you, everyone, for all of your questions. These were great. We talked a lot about the dollar devaluing compared to stuff. Obviously, we think gold is one way to protect against that. What are some other ways? The question is, what are the top two or three strategies to protect against the devaluation of the dollar?

Alissa: I think holding real assets. I remember in Germany, there was a story about somebody who their suitcase full of cash got stolen. When they stole the suitcase, they poured out all the cash and stole the actual bag. I think just owning real assets. We talk a lot in our research team about what assets are going to be – is that money going to be fully recognized in that asset? Gold and platinum and silver, those are naturally commodities that would see the full amount of money going into them. Other commodities too. How much will they see of that money can be debated, but it’s not going to be zero. Real assets are, I think, your best protection.

Dave: Best protection, but anything of value. Franchises are value. People are not wrong to think that the Mag 7 are going to hold their value over time. I suspect they’re overpaying for them. It’ll be like ’99, where if you bought those stocks in ’99, you’re doing well now, but you got slaughtered the next three years. In the long run, I think holding those kinds of stocks are fine. In the shorter run, you’re much better to buy similar companies in China that do the same thing, that sort of thing. Good franchises that are phone companies in emerging markets or the tech companies that win are going to be the winners. The important thing is that people buy things that arguably have value and don’t sit on euros and yen and dollar and yuan because 30 years from now, $1,000 won’t buy you breakfast anymore, if that is a possibility.

Mary: All right. We’ll leave it there for tonight or today, depending on which time zone you’re in. Dave, Alissa, do you guys have any concluding thoughts or comments for us?

Dave: No, not really. I appreciate you guys taking the time. It’s an interesting year. We look forward to talking to you again in three months and see how this year ended.

Mary: All right. Thank you, everyone.

[1] Kopernik Global Investors was launched by Dave Iben in 2013. References to times prior to 2013 draws on Dave’s experience at previous firms during his 43-year investment career.

[2] Kopernik Global Investors was launched by Dave Iben in 2013. References to times prior to 2013 draws on Dave’s experience at previous firms during his 43-year investment career.

[3] Kopernik Global Investors was launched by Dave Iben in 2013. References to times prior to 2013 draws on Dave’s experience at previous firms during his 43-year investment career.

The commentary represents the opinion of Kopernik Global Investors, LLC as of October 30, 2025, and is subject to change based on market and other conditions. Dave Iben is the managing member, founder, and chairman of the Board of Directors of Kopernik Global Investors. He serves as chairman of the Investment Committee, lead portfolio manager of the Kopernik Global All-Cap and Kopernik Global Unconstrained strategies, and co-portfolio manager of the Kopernik Global Long-Term Opportunities strategy and the Kopernik International strategies. These materials are provided for informational purposes only. These opinions are not intended to be a forecast of future events, a guarantee of future results, or investment advice. These materials, Dave Iben’s and Alissa Corcoran’s commentaries, include references to other points in time throughout Dave’s over 43-year investment career (including predecessor firms) and does not always represent holdings of Kopernik portfolios since its July 1, 2013, inception. Information contained in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but the accuracy of this information cannot be guaranteed. The views expressed herein may change at any time subsequent to the date of issue. The information provided is not to be construed as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any investment or security.

The Global Industry Classification Standard (“GICS”) was developed by and is the exclusive property and a service mark of MSCI Inc. (“MSCI”) and Standard & Poor’s, a division of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“S&P”) and is licensed for use by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. Neither MSCI, S&P nor any third party involved in making or compiling the GICS or any GICS classifications makes any express or implied warranties or representations with respect to such standard or classification (or the results to be obtained by the use thereof), and all such parties hereby expressly disclaim all warranties of originality, accuracy, completeness, merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to any of such standard or classification. Without limiting any of the foregoing, in no event shall MSCI, S&P, any of their affiliates or any third party involved in making or compiling the GICS or any GICS classifications have any liability for any direct, indirect, special, punitive, consequential or any other damages (including lost profits) even if notified of the possibility of such damages.