Hindsight is 1920 (Sep 2025)

It was January 1919, and Emma Harrington was incensed. San Francisco had just reinstated its mask mandate, and, for Harrington, being forced to cover her face violated her fundamental personal liberty. More than 4,000 people who attended the meeting she called on January 5 agreed. Their petition was presented to the city’s Board of Supervisors even as she fumed, with at least one sympathetic official declaring it undemocratic to compel citizens to wear masks that they considered ineffective or even harmful.1

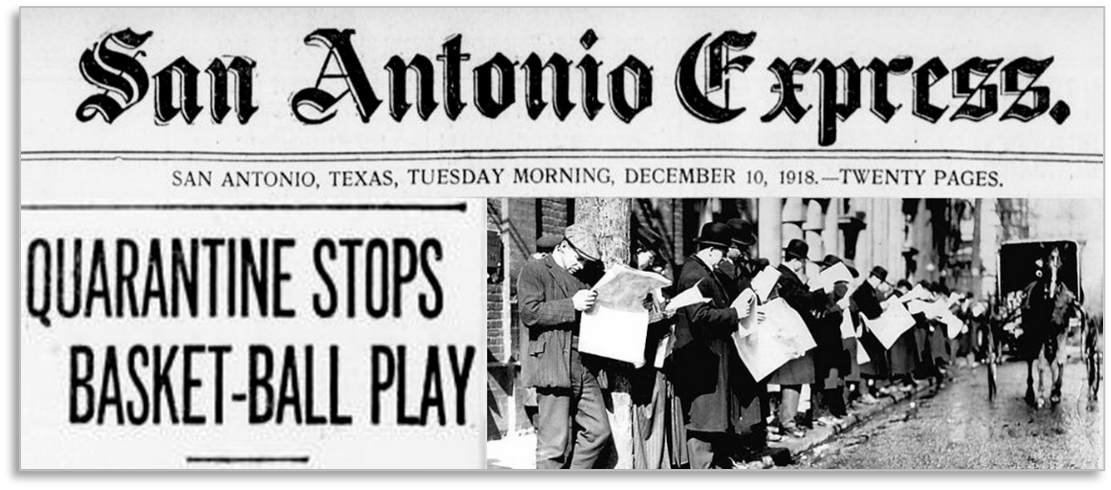

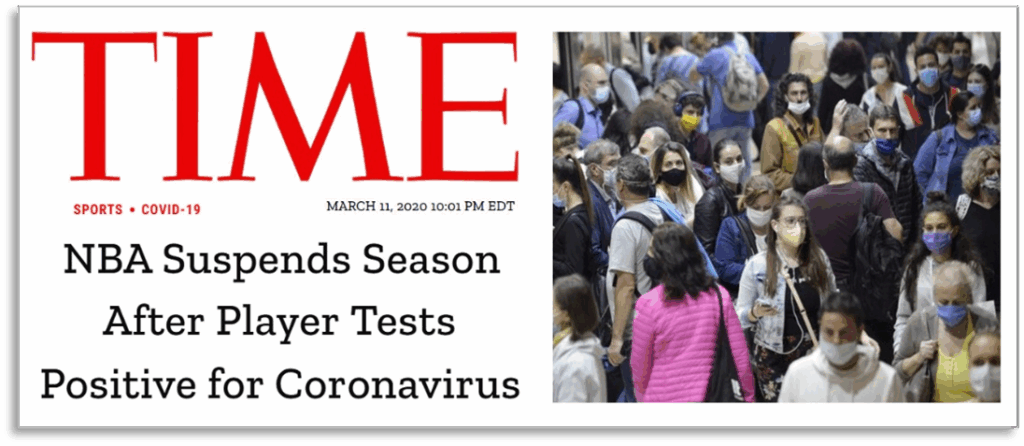

Sound familiar? Though this clash unfolded during the Spanish Influenza pandemic, a reader could be forgiven for thinking that it was from the Covid-19 pandemic a century later, when masking, lockdowns, and government restrictions again divided the public. In both eras, responses to pandemics not only polarized society, but also set off sweeping cultural, political, and economic shifts, ushering in decades that roared with change—and markets that roared their way to absurd highs.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

-Mark Twain

As observers of the rhyming nature of history, we have recently been struck by the similarities between the two decades and thought it worth exploring in more detail. What lessons do these comparisons hold? Likely more than we realized. Let’s begin with a framework that helps us understand the structure of the rhyme.

The Turnings of History

“Time brings all things to pass.”

-Aeschylus

In a previous life, I routinely taught the standard freshman-level U.S. history survey course, and I used to open my lecture on the 1920s by telling my students that, if I put them in a time machine and sent them back to that decade, they’d be able to survive. Much of life would feel familiar. In 1925, there were telephones, cars, radios, electric lights, baseball games, and even house parties (although the alcohol came courtesy of bootleggers). The 1920s was the first “modern” decade.

What made the “Roaring Twenties” remarkable, however, was not just its modernity but the stark contrast to the years immediately preceding it. World War I and the Spanish Influenza together killed more than 60 million people between 1914-1920, leaving trauma and disillusionment that writers like Wilfred Owen, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald captured vividly. When the guns fell silent in November 1918, no one knew how the generation that had endured such loss would respond. Their answer was a decade of cultural experimentation, social upheaval, and economic excess.

Generational theory, articulated by William Strauss and Neil Howe, offers one lens to interpret the cyclical nature of history. They argue that history moves in 80-to-100-year saeculums, divided into four “turnings” of roughly 20 years each.

- First Turning (High): strong institutions, unity, optimism (e.g., post-WWII era)

- Second Turning (Awakening): institutions challenged, cultural upheaval (1960s-1970s)

- Third Turning (Unraveling): institutions weaken, rising individualism, cynicism (1980s-2000s)

- Fourth Turning (Crisis): institutions collapse, requiring upheaval and reconstruction (2008-present?)

With that framework in mind, let’s consider what a comparison of the 1920s and 2020s might look like. Both eras seem like boom times—but cracks can appear quickly. Using the lens of the turnings of history allows us to think about many of the similarities in the two eras: challenging and weakening institutions, rapid technological change, a sometimes-absurd cultural milieu…and, of course, a booming economy and financial markets that defy sense.

Challenging Traditional Institutions

“If today you can take a thing like evolution and make it a crime to teach it in the public school, tomorrow you can make it a crime to teach it in the private schools…

At the next session you may ban books and newspapers.”

-Clarence Darrow, defense attorney, Scopes Monkey Trial, 1925

“The Supreme Court has been wrong. There is no separation of church and state in the Constitution or the Declaration of Independence. It doesn’t exist. So we will bring God back to schools and prayer back in schools in Oklahoma, and we will fight back against that radical myth.”

-Oklahoma State Superintendent Ryan Walters, 2023

Prevailing wisdom says to never discuss two things: politics and religion. For a moment, let’s put aside that advice, because describing conflict over religion is an excellent way to describe challenges to institutions in the United States. Religion has long shaped American institutions. In 2023-2024, 69% of Americans identified as religious. This religious prevalence mirrors the 1920s, when about 65% attended church weekly.2

Yet religious institutions have never been unified, and conflicts within them have been significant. The 1920s saw intense conflict, known as the fundamentalist/modernist controversy, pitting traditionalists against those seeking to adapt faith to modern society. What started as tensions over doctrine and religious practice spilled into public schools, especially over whether to permit the teaching of evolution. Thirty-seven states considered laws restricting the teaching of the theory; four enacted total bans, and two others imposed textbook limitations. The resulting legal battles, especially the Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925, highlighted deep divisions between religious and secular values. Because the Scopes Trial was one of the first major national events broadcast via radio, it blossomed into a nationwide media spectacle that made the religious fundamentalists look foolish, even though Scopes was convicted (his conviction was later overturned on a technicality).

The 2020s has also endured its share of vociferous public conflicts over the role of religion in the education system; my own home state of Oklahoma has been at the forefront of this debate courtesy of its vocal (and unpopular) State Superintendent of Education Ryan Walters, who has suggested that Bibles should be required and used as curriculum materials in 5th-12th grade classrooms. Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas have recently attempted to pass laws mandating that the Ten Commandments be displayed in every public school classroom. Like the anti-evolution statutes of the 1920s, these have faced significant legal challenges.

What stands out most about these conflicts, though, is not so much their specific content, but the relentless wave of institution-challenging they generate. One institutional challenge feeds into another—churches challenge each other, state laws challenge the Constitution, and secular groups challenge religious entities and vice versa. These disputes create a nonstop wave of conflict, with institutions constantly questioning each other’s legitimacy. This cycle leaves organizations, from churches to courts, locked in a whirlwind of rapid, repeated challenges.

Across the board, public trust is low. Only 34% of Americans say, “most people can be trusted,”3 but if you look at trust in institutions, the numbers are even lower. According to Gallup:

- 17% of Americans have a “great deal” of trust in the presidency; 10% of Americans have a “great deal” of trust in the Supreme Court, and only 4% express a “great deal” of trust in Congress

- 11% of Americans express a “great deal” of trust in banks and public schools

- 6% of Americans express a “great deal” of trust in newspapers, while 5% have a “great deal” of trust in television news

- 20% of Americans have a “great deal” of trust in the police, but only 5% have a “great deal” of trust in the criminal justice system4

The relentless questioning of the establishment and the status quo not only weakens individual organizations but also undermines stability, reflecting a broad crisis of confidence in the institutions meant to unite society and govern the nation.

The Challenges of New Technologies

“And now we know what we have got in radio—just another disintegrating toy.”

-Jack Woodford, Forum magazine, 1929

“The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race.”

-Stephen Hawking, physicist

Technological change disrupts the status quo, rapidly altering daily life, work, and society. Periods of accelerated change, like the 1920s and the present decade, create heightened uncertainty and a sense of dislocation.

That doesn’t mean that technological change is a bad thing; quite the contrary. Many of the technological developments of the 1920s are still in use today and have significantly improved the quality of life for many people. Automobiles made long-distance travel possible. Vacuum cleaners increased the efficiency of housecleaning, freeing up time. Electric traffic lights solved a problem caused by the emergence of the automobile. Penicillin, the first antibiotic, drastically changed medical practice. Many of the technological changes of the 2020s hold the promise of great change as well. In the realm of artificial intelligence (AI), in particular, the potential implications are just beginning to be understood. Some estimates suggest that AI will increase productivity by 20-30%. In Tampa, FL, where Kopernik is based, the University of South Florida is partnering with the local teaching hospital to use AI to detect pain levels in premature newborns whose lungs are not yet developed enough to cry5. A noble use of new technology, indeed.

Still, every advance challenges traditions and sparks fear. Cars were met with anxiety about traffic accidents and pedestrian safety; other observers decried the speed and frenetic pace of society that was reflected in automobile culture. Today, AI faces legitimate concerns about job displacement and academic integrity. As with the institutions described above, nothing goes unchallenged.

Rapid technological change often, although not always, flattens out the access hierarchy—a 1928 Ford Model A started at $385, making it affordable for broad segments of the American middle class. The average annual income in 1928 was $6,079, meaning a new Model A cost 6% of an average worker’s pay6. Ford’s revolutionary use of the assembly line and mass production not only slashed costs but made cars accessible to millions who could never have dreamed of owning a car a decade earlier (or, for that matter, in 2024, when the average price of a car was $48,400, an astounding 58% of the median annual income of $83,730). The number of cars in the United States tripled during the 1920s, from 7.5 million in 1920 to over 23 million by the end of the decade.

Technology can also democratize the spread of information; think about the rise of computers and the internet in the 1990s. In 5th grade, I was part of a group of students who decided to write and publish a school newspaper; we met at my house because I was the one person in the group whose parents owned a computer (and printer!). By the time I was in high school, less than 5 years later, every single one of my classmates had a computer at home, and by the time I graduated from college, less than 10 years after that, we carried computers in our pockets. It’s one person’s experience, to be sure, but it reveals how rapidly the transmission of information can shift.

The same was true in the 1920s. By far the most popular invention of the 1920s was the radio. In 1922, sales of radios and their parts and accessories amounted to $60 million. In 1929, that figure was $842.5 million, an increase of 1400%7. Radio brought the world into your home. It brought news events, storytelling, and music into the living room, quite literally making them part of the daily routine of life. Listeners were in Dayton, Tennessee, following the Scopes Trial and debating the outcome. They were in Washington, DC, for Calvin Coolidge’s 1925 inaugural address. They were in New York as Babe Ruth hit his record-setting 60th home run of the 1927 season. No longer were these events abstract; instead, they were a part of everyday life. Gathered around the radio after dinner, families were not observers, but participants in a new form of mass culture.

The Rise of Mass Cultural Absurdity

“I am the luckiest fool on earth.”

-Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly, flagpole sitter, 1929

“People don’t come to see the tigers; they come to see me.”

-Joe Exotic, 2020

The “Roaring Twenties” instantly conjures images of jazz, flappers, bootleggers, and gangsters. Absurdity and excess were central to the era, embodied in the odd fad of flagpole sitting. Flagpole sitting is exactly what it sounds like: a person sitting on top of a flagpole for days at a time to draw crowds and media attention. Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly became the symbol of this trend, spending 23 days atop a Baltimore flagpole and garnering both accolades (the Baltimore mayor praised him as a “demonstration of the old pioneer spirit”) and scorn (Cosmopolitan magazine called his antics “competitive imbecility”).8

The 2020s also came in with a roar—a tiger’s roar. For a brief period early in the pandemic, American society was captured by the utterly absurd cultural phenomenon that was Tiger King. Detailing the lives, antics, and crimes of two larger-than-life personalities, Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin, the Netflix series became an instant hit with 34 million viewers in the first 10 days of streaming.

Admittedly, it’s much harder to offer cultural analysis of a current decade than a past one—hindsight is 1920! But with Tiger King as our guide, perhaps we can safely say one thing: a lot of the cultural moments of the decade have been, quite simply, weird. Social media, especially the rise of video apps like TikTok, allows people to become famous for publicly making fools of themselves.

The culture of the 1920s was mass culture, but the culture of the 2020s is a mass internet culture. In the 1920s, radio connected millions with shared broadcasts—news, entertainment, and events—turning personal experiences into collective ones. Mass culture today, fueled by TikTok and other social media, rapidly creates viral trends and internet celebrities, often by rewarding spectacle and encouraging herd mentality. Critics like Theodor Adorno worried that radio undermined individuality and fostered conformity; modern social media has been (rightly, in this author’s opinion) criticized for the same, as well as for increasing symptoms of anxiety and depression, especially in teens. Mass cultural phenomena don’t just reflect herd mentality; they actively fuel it, drawing individuals into collective ways of thinking and behaving that prioritize viral conformity over independent judgment.

The Economy and Financial Markets

“The excess stimulation from [the government] is to be reckoned

a cause of trouble rather than a source of the cure.”

-President Warren G. Harding, September 1921

“We are going to give a little coup de whiskey to the stock market.”

-Benjamin Strong, Governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1927

“I’m here to…be part of this moment, this movement…I risk my money happily.

I am not the least bit scared or worried. You might be a financial expert, I am a survival master.”

r/wallstreetbets user u/Hungry_Freaks_Daddy (early 2021)

Any discussion of herd mentalities in these two decades would be remiss without a discussion of financial markets (especially in a piece by an investment firm!). For as much as the challenging of traditional institutions, the emergence of new technologies, and the rise of absurd mass cultural phenomena gave the two decades their flavor, it was the attitudes and atmosphere of the financial markets in the 1920s that had severe and lasting impacts on the lives of many Americans. Those same markets were the ones that policymakers claimed to have “learned from” in the 2010s-2020s—all the while repeating many of the same mistakes of the earlier decade.

In both time periods, there is a sense of frenzied urgency and herd mentality that plays itself out in the markets. Things are great! Stocks only go up! No price is too high! You only live once! (YOLO!) The result? Speculative investment, overvalued markets, and, eventually, history suggests, a falling back down to earth.

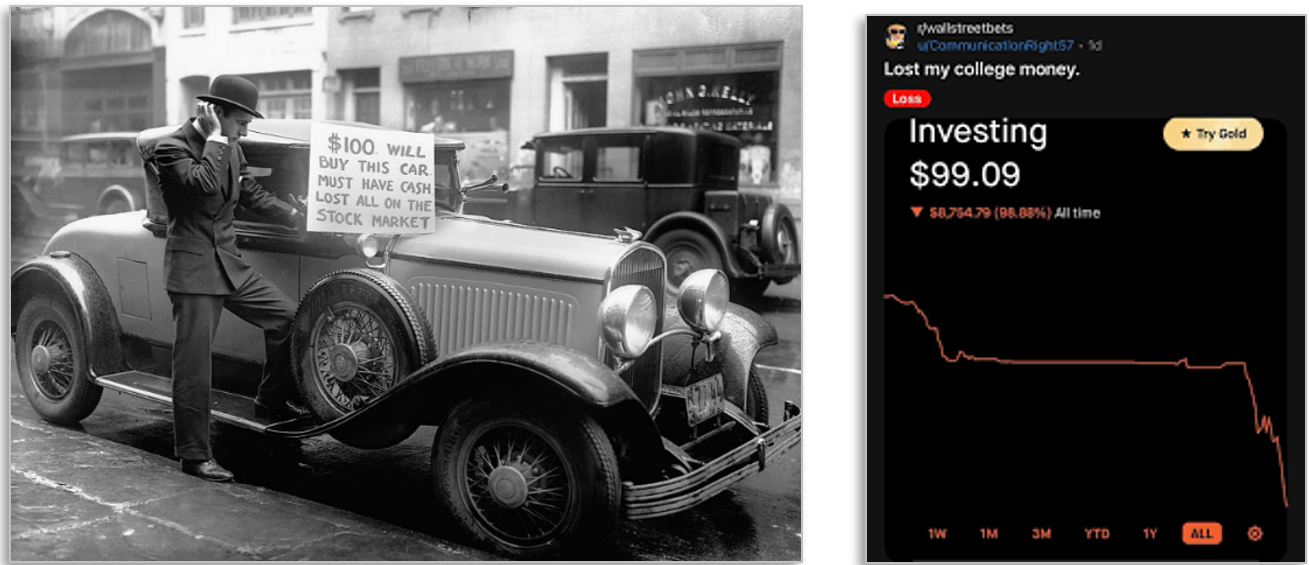

Nothing illustrates this better than the r/wallstreetbets Reddit community, whose activities drove the Meme Stock frenzy of 2021. Dramatized in the 2022 film Dumb Money, the story of their involvement in the GameStop short squeeze is well-known at this point: retail investors, utilizing Reddit as a source of communication and investment advice, used platforms like Robinhood to begin buying GameStop shares in the hope of squeezing out hedge funds and others that were shorting the stock. GameStop’s price skyrocketed, up by 1500% in two weeks. For our purposes, though, what happened is much less interesting than how it happened. The use of a social media platform to whip a crowd into a frenzy about something isn’t new. But r/wallstreetbets is an entire community dedicated solely to aggressive, high-risk investing strategies. It is, essentially, a forum dedicated to stoking the madness of the crowd, to celebrating speculation, and to clowning around in the stock market. GameStop stock is down more than 70% from its highs as of this writing (after bouncing back from being down 86% at the low)—clearly, speculating doesn’t work for long.

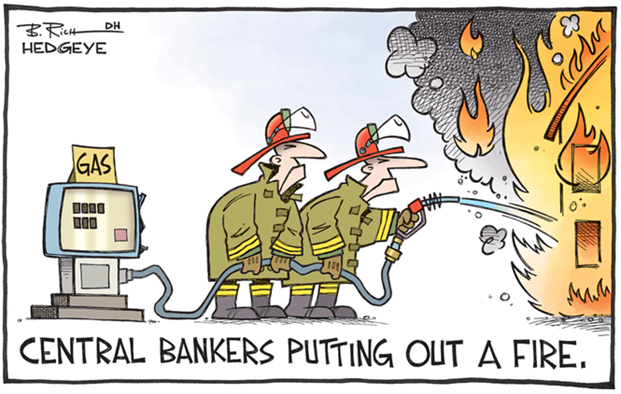

There are other similarities between the two decades as well: a Federal Reserve (“Fed”) whose monetary policy was less than sound, resulting in a combination of low interest rates and a torrent of conjured money that spurred malinvestment and drove up inflation; and unsustainable levels of debt, both individual and public. Let’s begin with what was, in the 1920s, a relatively new player in American monetary policy: the Federal Reserve.

As discussed in Creature from Jekyll Island, when it was founded in 1913, the Federal Reserve’s main role, officially, was to prevent bank panics (such as those of 1893 and 1907) by injecting liquidity into the system and supervising the banks to which it loaned money; it could also set the discount rates at which it loaned to banks. This is a far cry from the nationwide interest-rate setting, monetary-policy-making role of the Fed today; that power wasn’t technically granted to the Fed until the Great Depression, when the Banking Act of 1933 created the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, the FOMC has regularly taken actions that aren’t clearly within its mandate. (If one can even determine what its mandate is…the unprecedented interventions in financial markets, expensive asset purchases, and direct efforts to stabilize the economy blur the lines between monetary policy and broader economic management.)

In perhaps the best example of how history is told by the victors, the Federal Reserve maintains to this day that it bears no responsibility for the conditions leading up to the Stock Market Crash of 1929. The Fed points to constraints like the gold standard and prevailing economic theories as limiting its actions. Yet critics, especially Austrian economists, argue that the Fed’s monetary policies in the 1920s created the speculative environment that ultimately triggered the crash. (To get a sense for this debate, read Ben Bernanke’s Essays on the Great Depression alongside Murray N. Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression.)

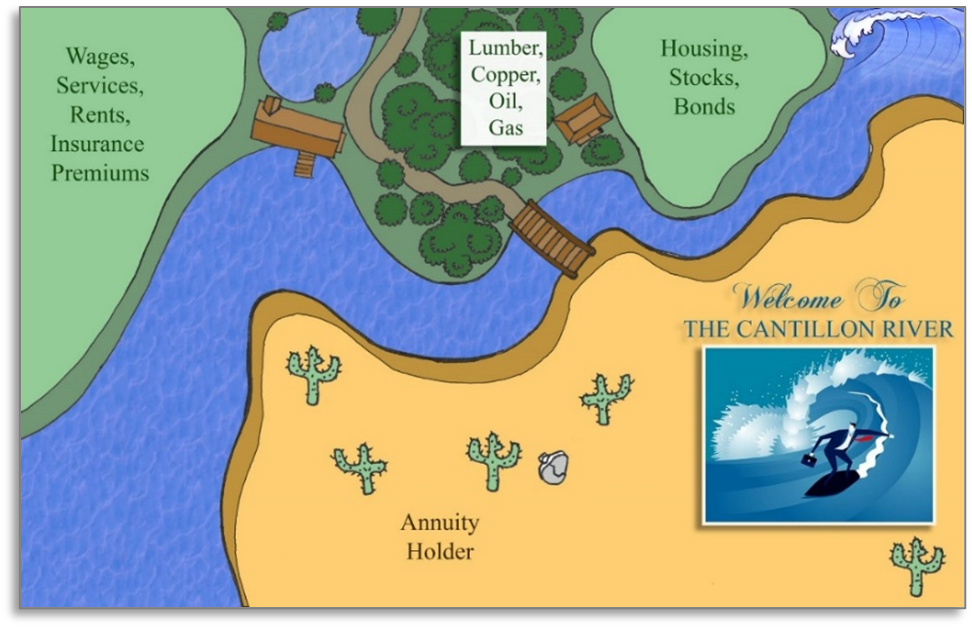

The Federal Reserve’s monetary policy in the 1920s foreshadowed the same types of tools that it would use in later crises: stimulus via an inflated money supply and low interest rates, which inevitably lead to price inflation and encourage malinvestment. While the word “inflation” is frequently associated with prices increasing, it’s important to remember that inflation is, at its most fundamental level, an increase in the supply of money, and the money that’s pumped into the headwaters of the river flows downstream and spreads out accordingly, pouring into different assets at different times. We have discussed this idea, popularized by the 17th-century economist Richard Cantillon, in prior commentaries and whitepapers, but it bears repeating an image we’ve shown before:

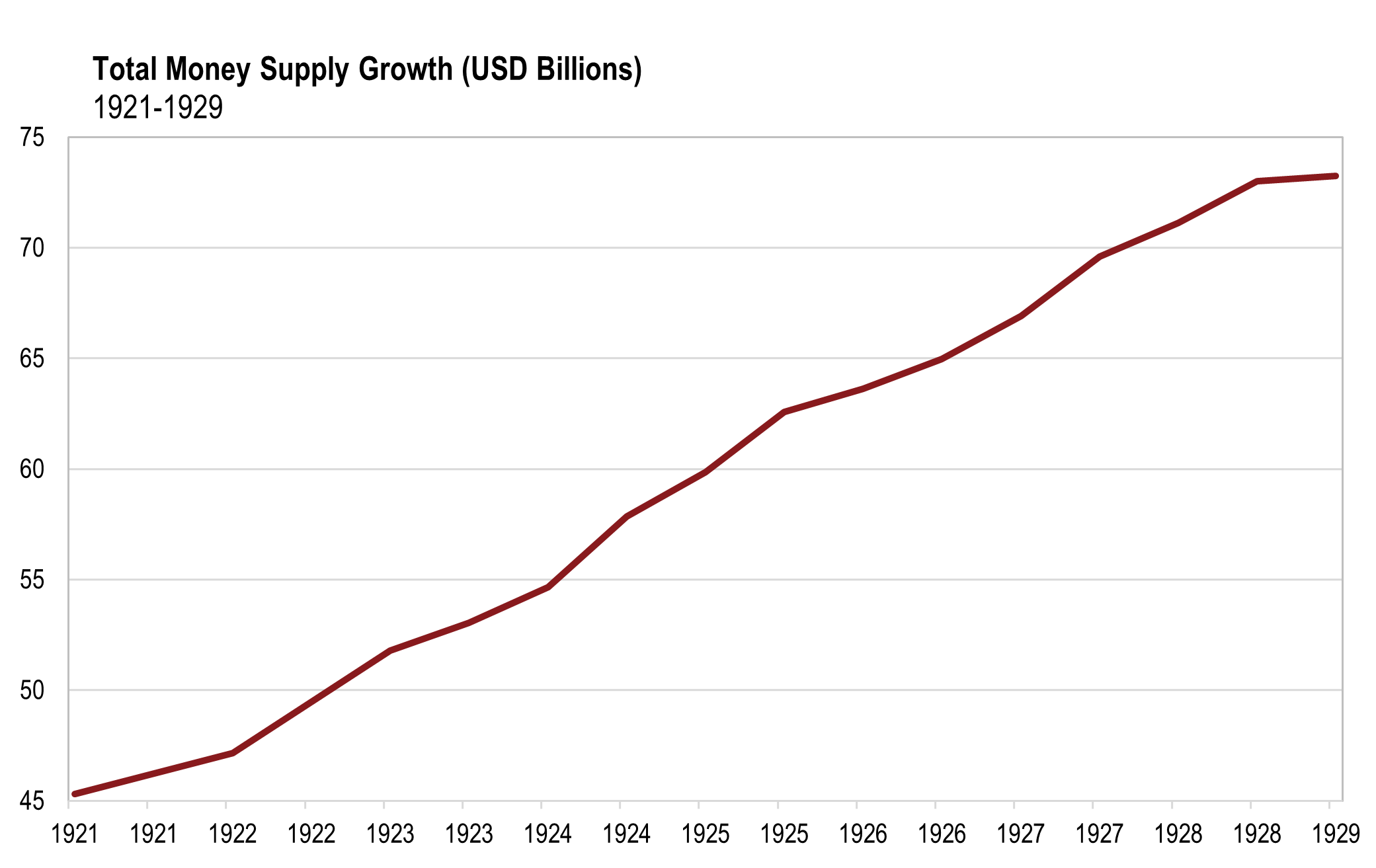

Price inflation was volatile in the 1920s (a brief recession in 1920-1921 meant significant deflation, followed by rising prices), but the overall stated price inflation rate for the decade was 0.38%9. Price inflation comes far downstream on the Cantillon River. If we journey to the headwaters, we can see that money supply inflation in the 1920s was significant, averaging about 7.7% per year (a total of 61.8% between 1921-1929)10.

Importantly, money supply growth in the 1920s wasn’t fueled by more cash in circulation or by a significant increase in gold reserves—gold reserves rose 15% while total dollar claims on gold soared 63%. Instead, banks increased deposits and credit, using loopholes created when the Federal Reserve cut reserve requirements for certain types of accounts. Banks reclassified deposits to create excess reserves, driving up inflation11.

Money supply inflation ran parallel with irresponsible interest rate policy. Throughout the decade, the Fed held rates to levels below what was reasonable in order to support the British economy (a resoundingly clear example of how the “laissez-faire” foreign policy of the United States in the 1920s was anything but!). Pressure from British officials led the Fed to expand credit, making U.S. assets less attractive and helping stabilize the pound, but only temporarily. This set a precedent for using easy money as a crisis response12.

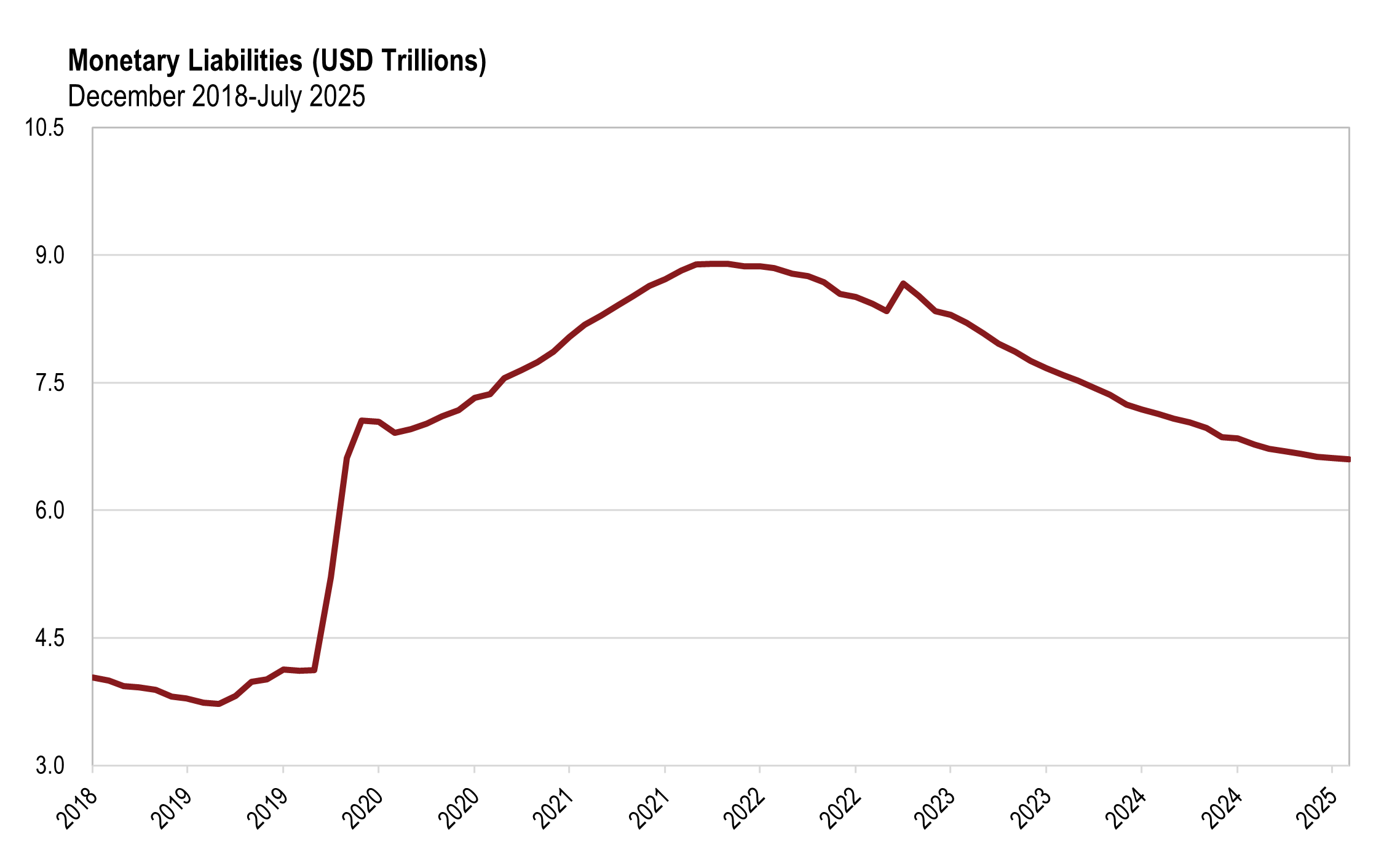

That strategy resurfaced during the Covid-19 pandemic, when the Fed once again poured money into the headwaters of the Cantillon River. The Fed’s balance sheet rapidly expanded from $4 trillion to $9 trillion through massive purchases of securities. (As the chart below shows, although it has come down somewhat, the Fed’s balance sheet still remains far above where it was pre-pandemic.) After keeping interest rates near 0% for 10 years after the GFC, the Federal Reserve again slashed them to absurdly low levels on March 15, 2020, and did not begin raising them until 2022, when CPI inflation was a stunning 8.5%—the highest since 1981. Once again, the Fed conjured printed trillions to support economic stimulus, echoing patterns established nearly a century earlier.

“Fair to say you simply flooded the system with money?”

“Yes. We did. That’s another way to think about it. We did.”

-Jerome Powell, Federal Reserve Chairman, CBS Interview, May 2020

Money supply inflation combined with interest rate suppression is a recipe for an inflationary bubble disguised as an economic boom. As financial historian Edward Chancellor points out in his excellent book The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest, “interest is required to direct the allocation of capital…without interest it becomes impossible to value investments.”13 Low interest rates encourage speculation; they allow people to take risks that they otherwise would avoid in the name of a larger return, because saving isn’t incentivized. There is, quite simply, nothing to put the brakes on malinvestment.

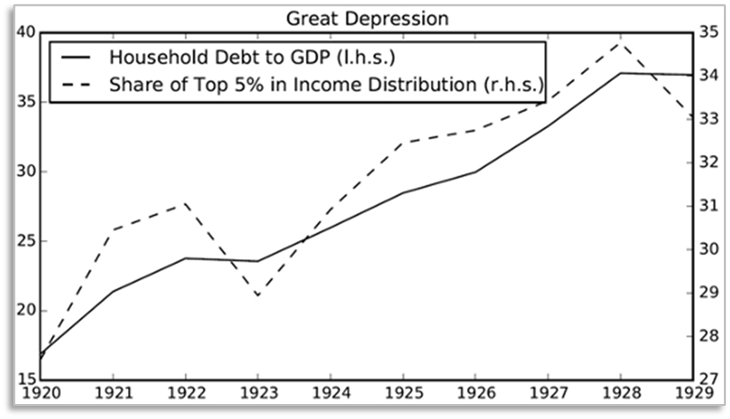

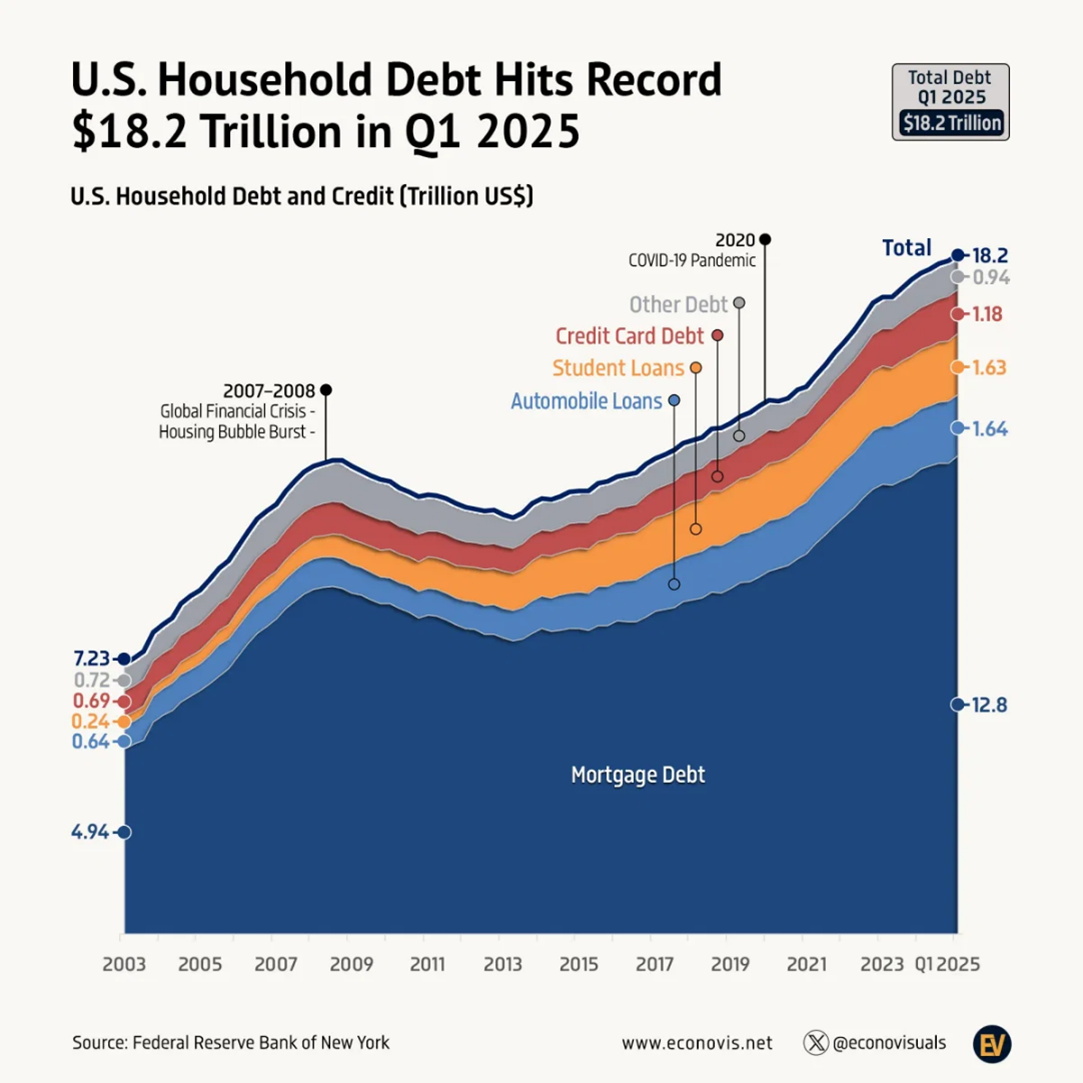

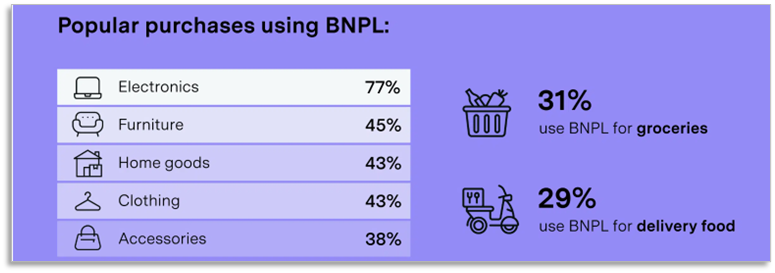

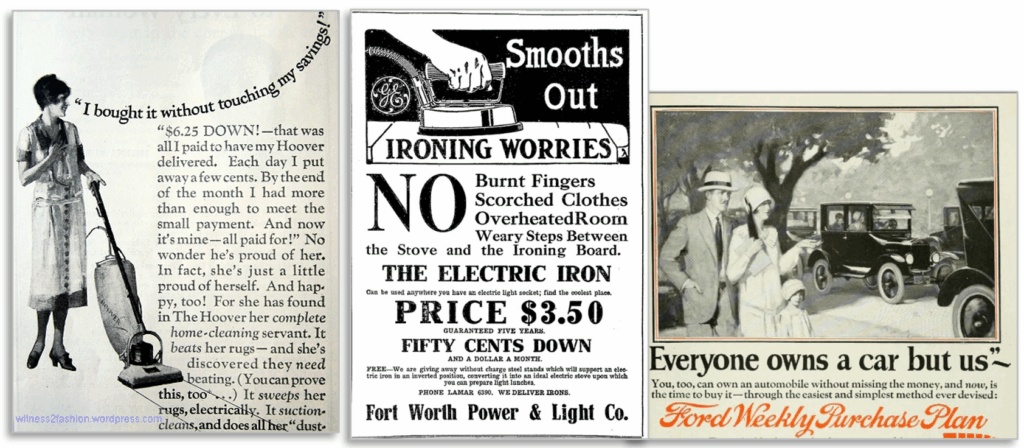

In this atmosphere, it shouldn’t be a surprise that borrowing escalated rapidly during both the 1920s and 2020s. In the 1920s, household debt to GDP climbed significantly. Installment loans were used to pay for nearly everything. Many of the consumer goods of the 1920s were big-ticket items—refrigerators, automobiles, washing machines, and radios. The use of installment plans, with a down payment and weekly or monthly payments until the item was paid off, made unaffordable goods accessible to a larger segment of the population. Credit is expanding rapidly during the 2020s as well. Low interest rates since the 2008 financial crisis have encouraged borrowing; the 0% interest rates of the Covid years drove that encouragement to full-throated cheering. Household debt has been climbing steadily since the beginning of the decade. The emergence of “Buy now, pay later apps” (BNPL) echoes the installment plans of the 1920s. The industry is rapidly expanding; Americans are using BNPL for a variety of items, including, concerningly, everyday essentials.

Advertisers in both decades emphasized the joy of instant gratification. In the 1920s, advertising campaigns emphasized the benefits that the new consumer contraptions could improve the quality of life; in the 2020s, BNPL users are portrayed as smarter and savvier than those who do not use the service.

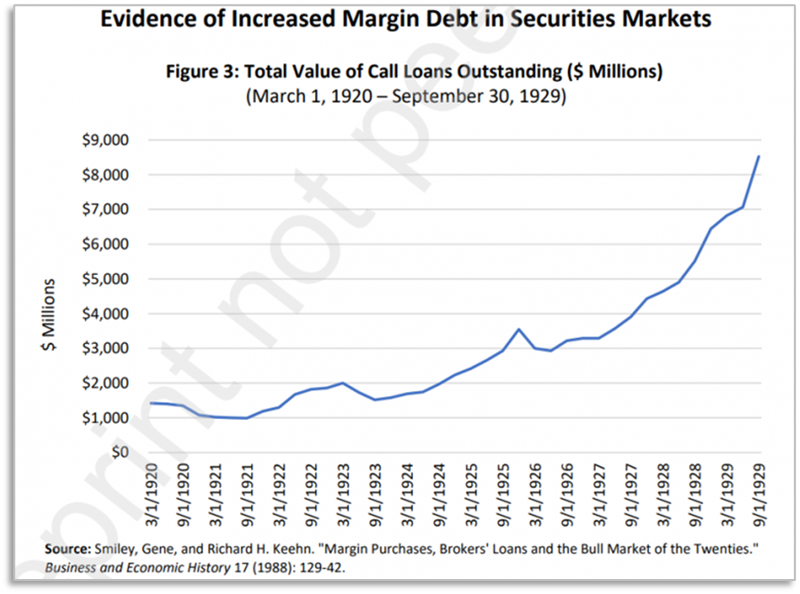

In both decades, borrowing extends from household debt and consumer goods to the stock market. In an era in which installment buying was de rigueur for consumer items, it makes sense that a similar mentality would be applied to stocks. Margin loans became commonplace; by 1929, margin credit accounted for 20% of the New York Stock Exchange’s market value. By August 1929, brokers had lent investors more than two-thirds of the face value of the stocks they were buying on margin—over $8.5 billion in outstanding loans14.

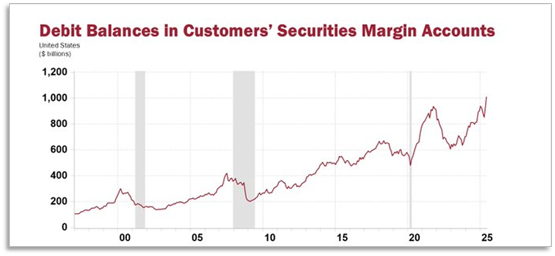

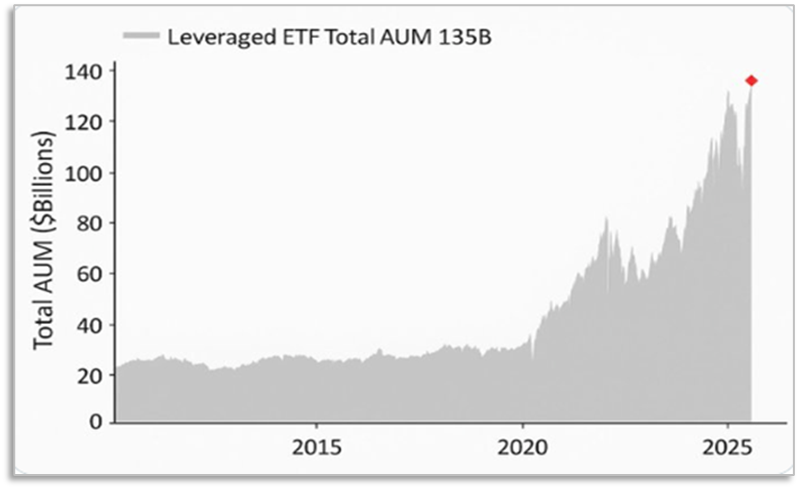

Although the use of margin accounts for retail investors is more highly regulated in the 2020s than it was a century ago, the use of debt to speculate remains popular, and margin debt has surged in recent years; according to FINRA, it peaked in June 2025 at $1.01 trillion15. One-fifth of all the leverage supporting the stock market has built up in the last year alone; almost half of the outstanding margin debt has come in the last five years. Highly leveraged ETFs promising up to five times the returns of the index they track are massively popular, with a total AUM of $135 billion as of July 2025.

Companies are issuing debt to buy crypto, leveraging up their balance sheets in the process. And there are other methods of debt-driven investing as well. Millennials have essentially only known homeownership in an artificially low-interest-rate environment, while markets have been screaming for a decade. Borrowing at 2.5% to invest in an S&P 500 index fund that has an average annualized return of 10% seems reasonable to many; in a survey of millennial homeowners, 30% of them approved of tapping into home equity to invest16. While these strategies may prove to be profitable, the risks are extremely high.

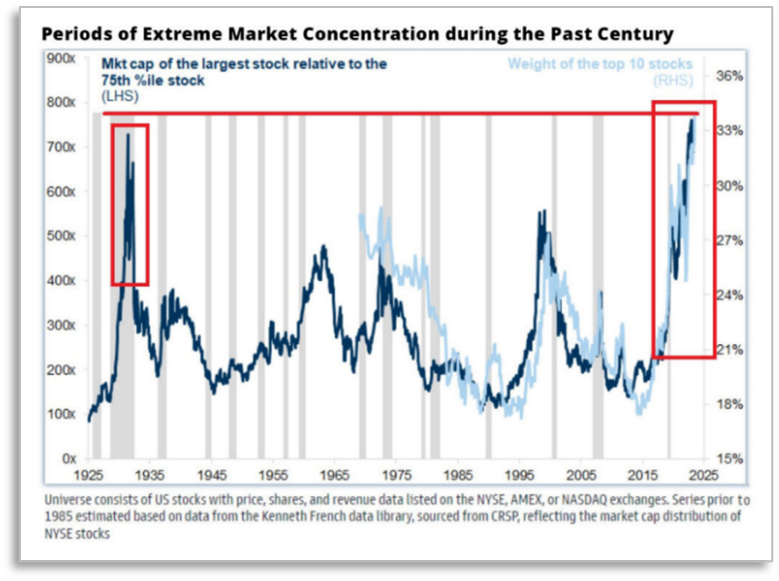

With the hindsight of 1920, we can safely say: we have seen this before. With markets characterized by a fear of missing out and herd mentality, where money flows freely and credit is easy, is it any surprise that speculative investments, frothy markets, and overvalued securities are once again the norm?

Investing in Uncertain Times

“When beggars and shoeshine boys, barbers and beauticians can tell you how to get rich,

it is time to remind yourself that there is no more dangerous illusion

than the belief that one can get something for nothing.”

-Bernard Baruch, My Own Story, 1957

“When your neighbor who’s never invested before starts talking crypto over the fence, pay attention.”

-Elizabeth Gaer-Leví, LinkedIn, 2024

From our position in September 2025, we can’t tell how this will end. But history tells us that it is highly, highly unlikely to go on forever. In October of 1929, the speculative party came screeching to a halt. Mr. Market stumbled and then fell. The New York Times industrials index fell from 452 to 224 in 2 weeks; by 1932, it had fallen to 58—an 87% drop17. With the hindsight of 1920, we can see that the result of the bubble popping was devastating. By 1933, unemployment was at 25%, U.S. GDP had contracted 30%, and roughly 44% of U.S. banks had failed (taking savers’ deposits with them—the FDIC and its deposit insurance didn’t come onto the scene until 1933).

Standing on the precipice in 1929, very few people could imagine a future any different from the past. Full of certainty that what had worked would continue to work, they saw no reason to do anything different. The result of this way of thinking was disastrous for many. Standing in 2025, with 95 years of hindsight, perhaps we draw a simple conclusion: “this time is different” is very rarely true.

In the late 1920s, like today, very few people were doing fundamental security analysis. Even famed value investors Benjamin Graham and David Dodd struggled to justify fundamental analysis during the peak of the mania. After all, if the fundamental analysis of a stock discourages buying something that is “going to the moon” (in 2020s parlance), the analyst is subject to career and reputational risk. When everyone wants to buy something, sounding the alarm is unpopular.

And yet, during moments of peak mania, those who hold back and act judiciously are the ones who can weather the storms. Bernard Baruch, known as the Lone Wolf of Wall Street, came through the 1929 crash relatively unscathed. While he made several speculative mistakes early in his career, by 1929, he had four decades of experience in the market and had seen firsthand how the herd mentality can take over. When the shoeshine boys were giving stock tips, major investors realized it was time to get out.

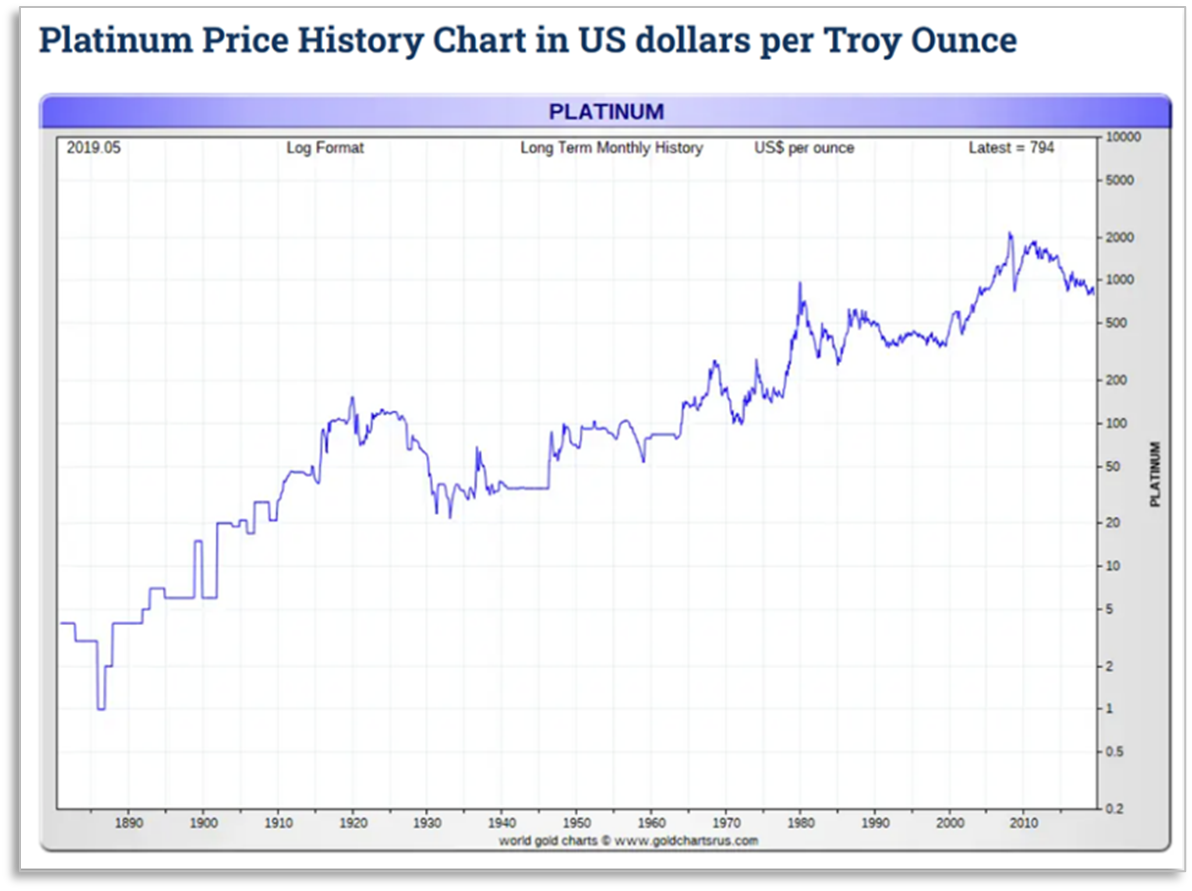

Are we at this point again in 2025? While a lot of the data points in that direction, history also gives us ample reason for optimism. It’s clear that outside those stocks, sectors, and countries most affected by the mania, other areas tend to be overlooked. For example, if history rhymes, investors may want to take notice that cash was one of the few safe places to be found in the early years of the Great Depression that followed the 1929 crash. Most assets plunged in price, relative to dollars; platinum, as it has in the past decade, fell during the manic years, but held its own during the crash and ensuing depression. It looks like it may be gaining strength recently, as the general mania is showing signs of subsiding. And the best place to have been in the 1930s was in gold, which appreciated almost 70% versus the dollar, and much more versus other assets.

Historical memories are short, but the echoes of the past are long. Manias never end well. Investors who lost everything in the crash of 1929 desperately sold possessions and joined bread lines. In the 2020s, people mourn their losses online (where else?), posting photo after photo of massive losses to r/wallstreetbets—the full consequences for many have yet to be understood.

Charles Mackey, author of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, said “it will be seen that [people] go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses one-by-one.” As they begin to recover from the mania of the last 15 years, it is probable that they will once again be attracted to the things they now find boring—dividends, cash flow, book value, intrinsic worth. One-by-one, they will likely migrate back to value. Perhaps this has already begun. We are optimistic about the future.

Historical manias and crashes remind us of something else: investing is a tremendous responsibility that requires careful thought and diligent management. The numbers on spreadsheets are more than figures; they represent the hopes and futures of individuals, families, and institutions. In short: investing is something to be taken seriously, not speculatively. The 1920s and 2020s both illustrate the importance of thinking judiciously—and that is a lesson that should resonate loudly across the decades.

We are honored to be stewards of your capital and are, as always, thankful for your continued support.

Mary Bracy

Managing Editor—Investment Communications

September 2025

Important Information and Disclosures

The information presented herein is proprietary to Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is not to be reproduced in whole or in part or used for any purpose except as authorized by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any product or service to which this information may relate.

This letter may contain forward-looking statements. Use of words such as “believe,” “intend,” “expect,” anticipate,” “project,” “estimate,” “predict,” “is confident,” “has confidence,” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current observations, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, estimates, and projections. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors, some of which are beyond our control and are difficult to predict. As a result, actual results could differ materially from those expressed, implied or forecasted in the forward-looking statements.

Please consider all risks carefully before investing. Investment strategies discussed are subject to certain risks such as market, investment style, interest rate, deflation, and illiquidity risk. Investments in small and mid-capitalization companies also involve greater risk and portfolio price volatility than investments in larger capitalization stocks. Investing in non-U.S. markets, including emerging and frontier markets, involves certain additional risks, including potential currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, less liquidity, less disclosure, and the potential for market volatility, expropriation, confiscatory taxation, and social, economic and political instability. Investments in energy and natural resources companies are especially affected by developments in the commodities markets, the supply of and demand for specific resources, raw materials, products and services, the price of oil and gas, exploration and production spending, government regulation, economic conditions, international political developments, energy conservation efforts and the success of exploration projects.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. There can be no assurance that a strategy will achieve its stated objectives. Equity funds are subject generally to market, market sector, market liquidity, issuer, and investment style risks, among other factors, to varying degrees, all of which are more fully described in the fund’s prospectus. Investments in foreign securities may underperform and may be more volatile than comparable U.S. securities because of the risks involving foreign economies and markets, foreign political systems, foreign regulatory standards, foreign currencies and taxes. Investments in foreign and emerging markets present additional risks, such as increased volatility and lower trading volume.

The holdings and topics discussed in this piece should not be considered recommendations to purchase or sell a particular security. It should not be assumed that securities bought or sold in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of the securities in a Kopernik portfolio. Kopernik and its clients as well as its related persons may (but do not necessarily) have financial interests in securities or issuers that are discussed. Current and future portfolio holdings are subject to risk.

- Journal of Proceedings, Board of Supervisors, City of San Francisco, January 27, 1919. ↩︎

- Pew Research Center, Religious Landscape Study, 2023-24; Study: Church Attendance Constant Over Years, Daily Free Press, February 21, 2002 ↩︎

- Americans’ Trust In One Another, May 8, 2025. ↩︎

- Confidence in Institutions, 2025. ↩︎

- St. Pete Catalyst, “USF Uses AI to Detect Pain in Silent Newborns,” July 31, 2025. ↩︎

- Model A Ford Club of America ↩︎

- Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday, 125. ↩︎

- “The Original Flagpole Sitter,” November 20, 1999. Reprinted on Baltimore or Less blog, 2012; “Holy cow! history: The luckiest fool in the world”, May 28, 2023. ↩︎

- Inflation and CPI Consumer Price Index 1920-1929, Inflationdata.com. ↩︎

- Murray N. Rothbard, America’s Great Depression, 5th edition, 93. ↩︎

- Rothbard, 95-100. ↩︎

- Rothbard, 142-159. ↩︎

- Edward Chancellor, The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest, xxii. ↩︎

- Wall Street Crash of 1929 ↩︎

- FINRA Margin Statistics. ↩︎

- Survey: Younger homeowners are more willing to tap home equity for nonessential, big-ticket purchases ↩︎

- Rothbard, xiii. ↩︎